This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Heber City • These hands once squeezed Xbox controllers and braced falls from skateboards, folded and threw newspapers, grabbed tight to wrestlers and slammed them to the mat.

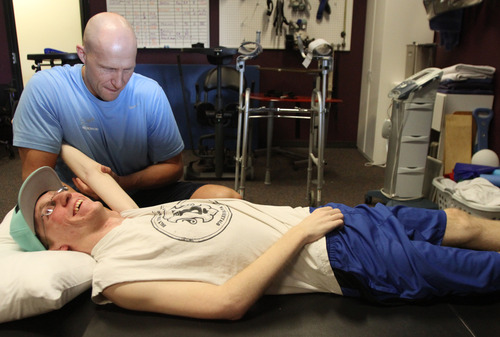

But now when Dale Lawrence gingerly lifts his left hand off the joystick that controls his wheelchair to softly greet a stranger, the simple action indicates progress, the result of two hard years of physical therapy.

Three times a week, the former Wasatch High wrestler makes the 45-minute trip from this quiet Utah valley to South Jordan for a few hours of exercise and workouts with machines that pump electrodes into his body. By the time early February comes around, the 20-year-old has exhausted the 15 sessions his family's insurance covers each year.

That's when catastrophic insurance takes over.

"They pick up what mine doesn't," his mother, Kelly Giles, said of the policy the Utah High School Activities Association has carried since the mid-1990s. "Otherwise he wouldn't be able to go back because we wouldn't be able to afford it."

Lawrence, whose vertebrae snapped into his spinal cord during wrestling practice in January 2011, is one of roughly 15 people who have benefited from the UHSAA's policy since it was put in place. This spring, the UHSAA's Board of Trustees will decide whether to renew that policy amid concerns about rising premiums.

If the board elects to discontinue the policy, some worry it could create gaps in coverage for future athletes and students as individual schools and districts try to shoulder the load. Others simply say the $1 million policy isn't enough to cover a lifetime of injuries.

—

Paying the premiums • When the sponsorship that covered the UHSAA's premiums dissolved, the association picked up the tab for its members. In recent years, half the revenue from football and basketball endowment games has covered most of that cost, while the association subsidizes the difference.

But two major claims — first Lawrence's injury, then the paralysis suffered by South Summit football player Porter Hancock in an October 2011 game — have resulted in a jump in premiums from $90,000 to more than $130,000 in the past year. The cost — about $3.50 per student — has begun to drain the UHSAA's endowment fund, leaving leaders to question whether the money should be spent on other things.

"What a tremendous blessing and benefit it's been to those families, but the premium continues to go up because of those payouts," UHSAA director Rob Cuff said. "It's a great benefit. On the other hand, is it cost effective and can we service the students in a way that can affect more than just the ones who by chance get injured?"

The money could be put toward sportsmanship, student leadership initiatives or any number of other uses, Cuff said.

Board members are just beginning to examine the issue, and a vote likely won't happen until sometime in March.

Region 14 trustee Matt Flinders, who represents South Summit, said he believes some districts would opt not to take on the cost of the insurance if the UHSAA stopped providing it. He said the association must find a way to continue the coverage, even if that means requiring districts and families to pay a portion of the cost.

"We can't say we couldn't buy this because we had to pay for some software," Flinders said.

—

Hit too hard? • Lawrence loved football and wrestling, but it wasn't his everything.

As a running back at Wasatch, he painted a superhero's mask on his face with eyeblack, earning the nickname "Super Dale."

On the mat, Lawrence practiced more than he wrestled, he said. In seventh grade, the first time he put on a singlet, he misheard a coach's instruction to exhibition wrestlers and never bothered to weigh in the entire year.

After that, he wrestled on and off with varying levels of enthusiasm, but he was excited to get back his junior year. He was a junior varsity captain and was winning more than he was losing while fluctuating between the 145- and 152-pound classes.

In practice on Jan. 4, 2011, Lawrence was down on all fours in a referee's position. A varsity wrestler was on top of him.

"I was just coming up and he was returning me to the mat," he said.

Whether he hit the mat too hard, or just awkwardly, a vertebrae snapped and cut his spinal cord.

His mother was off work that day and rushed to the school. By the time Giles arrived, the paramedics had decided to take her son to Provo. She sat in the front seat, and a paramedic blocked her view to the back when Lawrence stopped breathing.

—

Injury leads to advocacy • Eddie Canales watched his son make a touchdown-saving tackle during a high school football game in San Marcos, Texas, in 2001. It would be the boy's last play ever.

In the decade since, Canales has quit his job to take care of his son full time and lead a crusade through his nonprofit Gridiron Heroes to improve long-term care for high school football players who have been paralyzed.

In Texas, where the decision whether to carry catastrophic insurance is left to individual schools, many elect to pass on the policy. Of the athletes Canales has seen in Texas, just four of the 21 had catastrophic policies. His son's school in San Marcos had a $10,000 policy.

"That's not even one night in ICU," Canales said.

About half the states in the country do not have a statewide catastrophic policy for high school athletes. Of those that do, Utah, which has a 10-year policy with a $1 million maximum, is somewhere in the middle. The Michigan High School Athletic Association has a $500,000 policy with a $25,000 deductible. Montana has a lifetime benefit of $2 million.

The NCAA, meanwhile, has a $25 million policy for its athletes.

In a Gridiron Heroes case involving a paralyzed Chicago high school athlete, Rocky Clark was the beneficiary of a $5 million policy. After a decade of care, Clark had hit his cap and was left to rely on the scaled-back care covered by Medicaid. He died within a year.

"As big as football is in this country," Canales said, "that should never happen."

—

"Kind of in denial" • Lawrence's family used to live in a three-bedroom apartment in Heber, but after his injury the city came together and built them a large home on the west side, where passing train horns are one of the few things that break the silence.

His new bedroom looks like most any young man's.

There's a big bed and a big TV. There are posters on the wall — one for the computer game Diablo and another for one of his favorite TV shows, "The Walking Dead."

But look up to the ceiling and there's an overhead lift that snakes around the bedroom. The caretakers use it to put Lawrence in a sling and then lower him into his $2,500 shower chair.

Where a closet might be, there's an elevator to the basement. There's also a large, open shower area. The tile guy inlaid a yellow and black Super Dale logo against the gray.

On a recent Saturday morning, Lawrence's family showered him and dressed him in a red T-shirt, gym shorts and slip-on Vans. It's a job usually handled by the caretakers who come every week day — just as the insurance letters do.

Giles quickly stashes the envelopes away in a box, often without looking at them.

"I think I'm still kind of in denial," she said.

She doesn't know how much of the maximum benefit her son has used, but the catastrophic coverage has been important. It helps pay for the caretakers.

It covered the van and the wheelchair conversion kit, with its $62,000 price tag. It covers the $1,200 a month Lawrence uses in catheters.

"We'd have to re-use them" without that insurance, he said.

"I'd have to file for bankruptcy every so often," Giles added.

—

"Last thing you think about" • Not far away, in Oakley, Jill Hancock is receiving insurance letters, too.

Her son, Porter, was paralyzed while playing football for the Wildcats in October 2011. The catastrophic plan is the family's secondary insurance, and it pays out $1,000 each month, which the family uses for vitamins and gas to his physical therapy.

The Hancocks' family insurance covers 20 sessions each year.

"[Without the catastrophic coverage] he would definitely not be able to go to therapy as often as the doctors want him to," Jill Hancock said.

The insurance also paid for a standing frame and a $17,000 bicycle that sends electrodes into the teen's legs, helping decrease spasms and improve muscle mass and bone density.

At six months, the UHSAA's catastrophic plan paid out $50,000. The Hancocks bought a truck with a conversion system. Now the South Summit senior is getting stronger and can transfer himself into the truck by himself — though someone always watches him because he has spasms in his legs. He drives himself to high school and will drive himself to UVU next fall.

"It's definitely helped us a ton," Jill Hancock said of the UHSAA policy. "I didn't know there was such a thing. It's the last thing you think about."

—

Help fleeting • Dale Lawrence, the boy who used to squat 300 pounds and dead-lift 400 pounds, puts the handle of his spoon inside a thick piece of red foam — otherwise he might drop it when he eats.

He can hold himself up on the back of the couch sometimes, and with help and a walker, he's gone about 150 feet.

But Giles no longer believes her son will ever be able to walk on his own.

"What do you think, Dale?"

"I might," he said.

"He's got a better outlook than I do."

"Just a little bit," he said and he grinned.

"He don't ever have a bad day," she said. "How do you do it, Dale? It's not even me in your chair and I ... I can't. It's just hard."

Lawrence will be on his mother's insurance until he is 26. After that, he will rely solely on the catastrophic coverage — unless it has already been exhausted.

Flinders, the UHSAA trustee from Summit County, said he doesn't want injured athletes such as Lawrence and Hancock to be forgotten in time.

"The community raised tons of money, built them a house. Raised money to pay for the deductible and more," he said. "After a year or two, that goes away, and people kind of forget what happened. Those fundraisers don't keep coming."

Giles is already looking toward the future. A million dollars used to sound like a lot to her, but the money is going fast.

"How long's that going to last? That's what I worry about now. Even at 10 years, what's he going to do? Let's say it lasts that long," Giles said, her voice trailing off. "I don't know. This is a forever thing. It's not going to go away after 10 years."