This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

West Valley City • Painful divisions among Utah's Vietnamese Buddhists about ownership of the Pho Quang Temple in west Salt Lake City appear to be worsening.

Recent weeks have seen a protest outside another Buddhist temple and break-ins targeting the West Valley City offices of one of Pho Quang's original founders.

A judge ordered opposing factions to share the temple at 1185 W. 1000 North in Rose Park while litigation about who controls the property deed inches forward in 3rd District Court. Groups are holding competing worship rituals on Saturdays and Sundays, but it remains an uneasy arrangement.

"A lot of members cannot participate on Saturdays," temple co-founder Hoa Vo said. "That is very tough on us. So many people are suffering."

The conflict pits Vo, other temple organizers and their supporters against a California-based corporation known as the Vietnamese-American Unified Buddhist Congress, which is seeking control of the property on behalf of a group of Buddhist monks and nuns. Nearly two years into litigation, the case is moving slowly, punctuated by a series of motions for temporary restraining orders and protracted fights about potential evidence. A trial — if it comes to that — is unlikely until well into 2013.

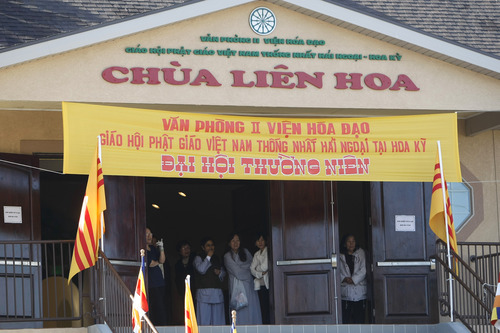

Frustrated backers of the temple founders staged their street protest last month outside the Lien Hoa Temple in West Valley City, hoping to draw the attention and sympathy of visiting monks from the Congress meeting inside. About 50 demonstrators chanted and waved signs near the temple gates, but the monks inside did not respond, in what several protesters pointed to as another sign that their local Buddhist community is being betrayed by religious leaders they once trusted.

"They were silent and didn't reach out to us," protest organizer Victoria Dang said. "They don't even talk to us."

For their part, Congress members say they are asserting legal control over the temple and its management in hopes of restoring religious stability to its adherents and bringing into line spiritually wayward congregation leaders. They often note that a significant portion of the Pho Quang congregation has sided with them.

The Congress, a U.S. branch of a religious organization outlawed in communist Vietnam, has sought to keep a low profile throughout the dispute, with its representatives saying the group is uncomfortable about publicity for what it views as more of a private religious affair than a legal matter.

"They don't like to have these types of battles and have sought to resolve this amicably," Salt Lake City attorney David Mortensen said. "The Congress is confident in its position and doesn't feel it is necessary to litigate it in the media."

The conflict is embarrassing to both sides and out of step with Buddhist tenets favoring harmony and compassion. It also highlights tensions between orthodox and secular aspects of Buddhist traditions transplanted from Asia to the U.S. and reaches deeply into Utah's growing urban Vietnamese immigrant community.

It may also be part of a bigger picture. The quarrel is uncannily similar to a fight in south Philadelphia among Vietnamese Buddhists about the Bo De Temple. There, too, temple members have clashed in court with the Vietnamese-American Unified Buddhist Congress about an attempted eviction, religious control, finances and temple ownership in a long-running schism that has left deep scars.

In Utah, Vietnamese Buddhists began worshipping at Pho Quang in 1996, when a group of as many as 100 first- and second-generation immigrants pooled resources and bought a former library after years of community fundraising. Through the years, they retrofitted the 5,952-square-foot structure with a worship hall, cloisters, classrooms and a shrine for ancestral ashes.

About 12 years ago, temple founders signed over the building's deed to monks belonging to the Congress. The transfer was partly a religious offering and partly a move to ease mutual distrust among members about management of the congregation's finances.

But the Congress never followed through on promises to send a resident monk to Pho Quang, leaving key ceremonial duties to lay worshippers, founders say. Financial disputes also emerged, coming to a head with construction of an $80,000 pagoda-style gate for the temple, which the Congress never authorized.

In 2011, the San Jose-based Congress transferred its ownership of the Pho Quang deed to a little-known group connected to head monk Thich Tri Lang, who oversees the Lien Hoa Buddhist Temple in West Valley City. The new deed holders moved last year to have local temple founders and their followers evicted. That ouster was halted in court.

Since then, the two sides have squabbled repeatedly about use of the temple, while they ready their cases before 3rd District Judge Kate A. Toomey. Court documents describe shouting matches, an altercation near the Rose Park temple's altar involving one leading nun and rancor about how to handle celebrations of Vietnamese New Year.

Legal wrangling also has focused on business documents and other evidence relevant to the case. At one point, local founders sought a partial protective order seeking to shield information on congregation membership and finances they considered private.

Then, sometime around Sept. 21, burglars ransacked three business offices adjoining the travel agency Vo operates in a West Valley City strip mall, leaving valuables and computer equipment but, Vo said, taking documents central to the Pho Quang lawsuit.

Adding to the intrigue, the burglary was discovered while Vo and fellow temple founder and lawsuit defendant Chuc Phan were across town being deposed in the case.

"It is strange to everyone, very odd and very suspicious," Vo said. "It's hard to believe that people weren't looking for those documents. They took them all."