This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Like all new parents, Daniel Mancuso and Shyanne Jensen thought their newborn daughter looked perfect when she popped out Nov. 19.

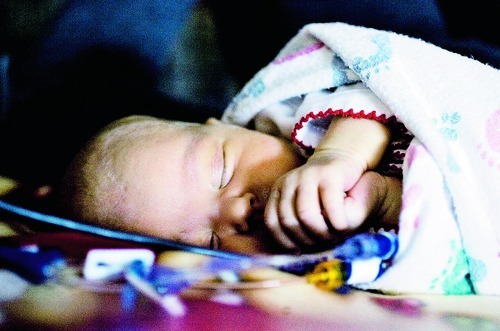

After all, baby Alicen weighed a bit more than 7 pounds and had all the requisite fingers and toes. She let out a strong cry in her first moments of life and could gyrate her limbs. She seemed willing to bond skin to skin with her eager mother and was, her parents say, already mugging for the camera.

But there was something wrong inside her.

Doctors attending the birth at Bozeman Deaconess Hospital in Montana noted that the baby wasn't pink enough. They poked and prodded, took X-rays and ultrasounds, weighed, measured and assessed. They had trouble detecting a heartbeat and found a large mass in the baby's chest.

Apparently, the baby's bowels had moved up through an opening in the diaphragm, her heart was pushed to the wrong side and her lungs had collapsed.

The situation was dire, and the baby's chances diminished with each passing hour. Doctors told her parents they needed to rush her to a bigger hospital in a bigger city, with physicians specializing in this condition, known as a "congenital diaphragmatic hernia."

And so for the past month baby Alicen has found herself in a glass crib in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Primary Children's Medical Center in Salt Lake City, while her parents hover nearby.

It is not a stable and there are no braying donkeys, or shepherds, or gift-bearing kings, for that matter. But on this day, when Christians everywhere celebrate the birth of a babe to a young couple far from home with few resources, the story of Daniel and Shyanne carries its own kind of Christmas magic.

Good tidings aplenty

It was the fall of 2009, and Daniel was feeling good. He had an easy and steady job as a groundskeeper at North Idaho College in Coeur d'Alene. He lived in a three-bedroom house on 5½ acres he had inherited from his grandfather. And the then-23-year-old had mostly recovered from a neck injury a few years back.

Then Daniel's cousin introduced him to Shyanne, a willowy 19-year-old with wonder-filled brown eyes and an optimistic disposition.

The skateboarding outdoorsman was hooked.

"I knew within four minutes I wanted to spend the rest of my life with her," Daniel recalls.

"I felt exactly the same way," Shyanne echoes.

He loved her laugh, her patience, her love of nature and "everything" about her. She was drawn to his kindness to others, his good heart and ability to make her laugh. They were emotional twins, he said, so alike and so compatible.

A few months later, Daniel invited Shyanne to move into his grandfather's house. He continued working at the college, while she attended a technical school in nearby Spokane, Wash., studying advertising. He hoped to be a pilot; she wanted to make movies.

With jobs, cars and a bright future, it wasn't long before they talked of having a child. Their love was solid, they felt, and they were ready to create a family.

When they learned Shyanne was, indeed, pregnant, Daniel grew so excited he "ambushed" her from her job at Chili's and drove straight to a doctor to set up regular appointments. They became fastidious about her health, vitamins and exercise. Daniel even went to her breast-feeding classes. He was the only male there, he says, but he didn't care.

Searching for an inn

Then their luck turned. Daniel injured his back running a commercial-size aerator, making it impossible for him to work. He was laid off.

Shyanne's car died, and he sold his to buy an '89 Honda Accord.

Later, his grandmother, who long ago had left his grandfather, returned to claim the house and evict the couple. They stayed with friends and family, then eventually moved into a room in her parents' condo in Bozeman.

Undaunted, Daniel and Shyanne were thrilled to be in love, having a baby and surrounded by people who supported them. He got a job busing tables at IHOP. She was carried on her parents' insurance. Friends and family gave them two baby showers, and they felt ready for their little addition.

But, on the eve of Alicen's birth, Shyanne read her horoscope, which said something like this: "A major event in your life will change your religious views." She found herself reflecting again and again on that prophetic pronouncement.

They came from afar, but not together

It took 18 hours of hard back labor and four hours of pushing to get baby Alicen born. Shyanne was excited but exhausted. She rested in bed as the doctors whisked her baby and boyfriend from the room.

When he returned, Daniel was ashen.

Though her mother and the doctors had instructed him not to give Shyanne the bad news, Daniel couldn't hold anything back from the girl he loved. He blurted it out.

"She's sick, and we have to take her to a hospital in Salt Lake City," he told Shyanne, thinking they would go together.

But the doctors said it would have to be him, not the new mother, who they feared might hemorrhage during the two-hour flight. The thought of separation horrified the new dad, who had spent only a weekend apart from Shyanne since they met. Now there was no choice.

So Shyanne quietly wept, while Daniel rushed home, tossed a few clothes into a backpack and scurried back to the hospital, just in time to hop in the ambulance headed for the airport.

"Watching them pack Alicen up for the flight was so scary," Shyanne recalls. "They hooked her up, took my boyfriend and my baby and said, 'Bye.' "

She felt dazed and alone.

On the way out of the hospital, someone called out, "Bye, Dad," and, Daniel says, "I was looking around for somebody's dad. Then I realized they were talking to me."

It took about eight hours — from Alicen's birth at 2:22 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. — to get the baby situated in Primary's NICU.

The frazzled father arrived with her in a strange city and hospital. Doctors and nurses took the infant in for evaluation, leaving Daniel alone in the hallway. A nurse showed him a sofa where he could crash and, though without sleep for nearly two full days, he dozed fitfully.

"I had no money, no friends, no family and no insurance," he recalls. "I was lost."

The next day Annette Proctor, a Primary social worker, took him to the Ronald McDonald House, where he and Shyanne (once she arrived) could stay for about $15 a day. Or whatever they could afford.

Daniel, who was reared a Christian, thanked God that day. And many times thereafter.

Angels attending and assisting

In her first week of life, Alicen underwent major surgery to restore the bowels and heart to where they belonged. It was a complicated operation, with many risks.

Daniel's mom, Becky Ross, flew in from Alaska to be with him.

Despite all her son had been through, Ross noted with pride the changes wrought by fatherhood.

"It clicked something emotionally in him that was profound," Ross said in a phone interview from her home in Alaska. "He realized you just have to keep on keepin' on."

Proctor also was impressed by Daniel's demeanor.

"It was a stressful time for him," Proctor says, "But he behaved very appropriately. He was very invested in the baby's care and concerned about [Shyanne]."

Meanwhile, Shyanne was both recovering from the birth and desperate to reunite with her baby and boyfriend as soon as possible. Her father and sister agreed to drive her down in the Accord, but the heavens decided to dump a load of snow that week. The threesome had to turn back in West Yellowstone and couldn't leave until the weather improved.

Six days after giving birth, Shyanne finally made it to the Beehive State — just in time for Thanksgiving. The couple and their family members gratefully feasted at the Ronald McDonald House.

Together at last, they began a daily trek to the hospital to watch over their babe's recovery.

A third of the babies born with a congenital diaphragmatic condition die soon after birth, they learned. A third live with lifelong medical problems, often including a colostomy bag for waste. Only a third do as well as baby Alicen, who came through the first surgery swimmingly. She wasn't on oxygen and was feeding fine.

Unfortunately, the baby had to undergo a second operation within two weeks of the first to deal with complications. The couple, though disappointed, were grateful for every gift, every kindness, every friendly gesture.

A social worker showed them how to arrange for Medicaid. Doctors patiently — and in plain English — explained their baby's condition. Nurses gently cared for her and befriended them.

The two found themselves connecting to each other — and the heavens — more often and more urgently.

"We've called out to God and he's answered us," Daniel says. "Everybody's been so wonderful."

A newborn faith

Every night they meet with a chaplain, who prays with them at the hospital. Daniel regularly reads and explains Bible stories to Shyanne, who never paid much attention before.

In that study, they have begun to feel blessed.

Take transportation. The Ronald McDonald House provides a free shuttle to and from the hospital, but it doesn't always fit their schedule. Sometimes they catch TRAX or a bus. Sometimes they can't afford transit, so they walk.

One day, an anonymous donor gave them an envelope with $200. Later, when they reached their last $20, another family gave them a handmade quilt, a holiday card and $300.

"I've been in and out of faith since my childhood," says Daniel, now 24, "but I know my life is miserable without God."

For Shyanne, 20, the experience has been life-changing, just as her horoscope predicted. Her faith has enlarged as her baby continues to recover and thrive. Alicen now eats and poops and, if all goes well, may go home in a few weeks.

"It's been one blessing after another," Shyanne says. "No baby in this condition is supposed to do this well."

The young mother and father believe it was no accident. It took a miracle, they say, and lots and lots of prayer.

This will be a different Christmas than they likely will ever have again, Proctor predicts, but one they never will forget.