This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

For past coverage of the trial, including transcripts of testimony from Elizabeth Smart and Wanda Barzee, visit http://www.sltrib.com/topics/mitchell.

A former shoe store clerk testified Monday that Brian David Mitchell once referred to himself as Christ and asked her to join him and his wife in plural marriage.

Julia Adkison said she met Mitchell in 2000 when he came into the Fashion Place Mall to buy sandals from a store where she worked. Mitchell, who was dressed in robes and accompanied by his wife, learned that she had grown up in a Mormon fundamentalist group that supported polygamy, she said.

When she asked Mitchell what religion he and his wife were, Adkison testified, he replied, "I am Christ." He later said they tried to be Christ-like, she said.

Adkison — who left the Kingston polygamous group in August 1999 — was testifying at Mitchell's trial on federal charges of kidnapping and unlawful transportation of a minor. Mitchell is accused of kidnapping then-14-year-old Elizabeth Smart from her Salt Lake City home in June 2002 and holding her captive for nine months.

Defense attorneys say Mitchell was insane at the time of the offense. He faces up to life in prison if convicted.

Adkison said she saw Mitchell a handful of times, including in downtown Salt Lake City, where she was transferred to the same shoe store in the now-defunct Crossroads Mall.

One day he was panhandling and when someone walked up to him, he threw up his hands and start humming, she said. After someone gave him money, Mitchell returned to talking to her in a normal tone, Adkison said.

In February 2001, Mitchell requested a longer meeting with her and she talked to him and his wife, Wanda Barzee, for four hours in a seating area in front of a downtown building, according to Adkison. Mitchell said it was time to start living polygamy and asked her to join their family, she said. Barzee backed him up, she said.

Adkison said she never considered the proposal and declined. Soon after, Mitchell came into the shoe store and gave her a letter dated March 1, 2001, she said.

"He told me God would show me that what he was saying was true," she said.

The voice in the letter changes partway through and he starts writing as if he were Christ, Adkison said. "He's definitely putting himself up on a pedestal," she said.

Under questioning, Adkison said she did not recall Mitchell ever saying he was the Davidic King or would battle the Antichrist.

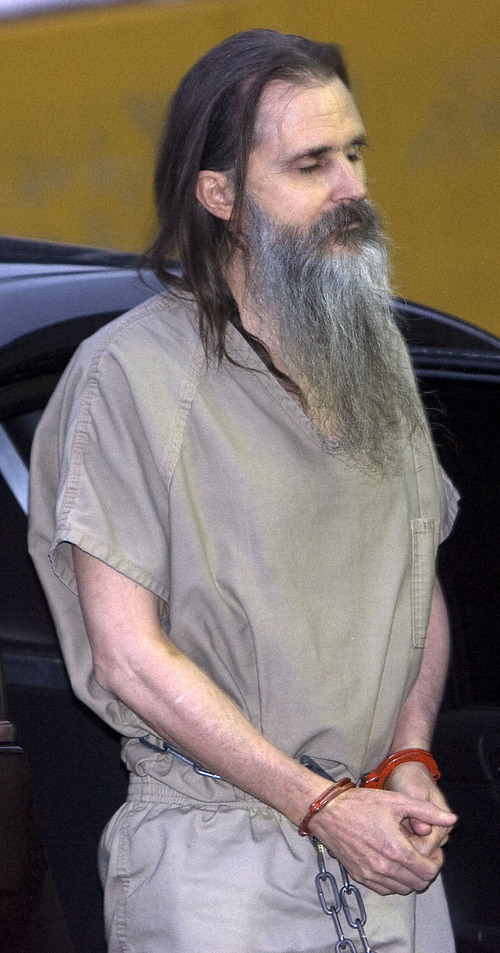

Mitchell was observing the proceedings through a video feed from a nearby room. He had been removed from the courtroom for continuing to sing after being warned by U.S. District Judge Dale Kimball to stop.

Throughout the morning, the prosecution's witnesses shared anecdotes of encounters with Mitchell, each one aimed at showing the man has the ability to reason and is not the delusional zealot the defense presented in its case last week.

In one account of testimony that was stipulated to by both sides, Gregory Schwitzer, the president of Mitchell's LDS stake, was given a copy of the Book of Immanuel David Isaiah and thought it was "well written" and its content and meaning amounted to apostasy.

Schwitzer called for a disciplinary hearing and kept a letter informing Mitchell of the hearing with him because he often saw Mitchell panhandling downtown. One day he saw Mitchell, and handed him the letter. Mitchell looked at the letter, threw it on the ground and yelled loudly for Schwitzer to repent.

Schwitzer later presided over the disciplinary hearing and Mitchell's excommunication from the church.

Robert Randell, a Salt Lake City patrol officer, arrested Mitchell in September 2002 for shoplifting — trying to steal batteries, gum, a flashlight and some beer — from a downtown Albertson's. Mitchell told Randell his name was "Go With God" and his birthday was "sometime after Christ."

After putting the man in his patrol car, Randell spoke with him.

"I said, 'Look, dude. Pretty simple. There are two ways we can go with this. No. 1, you can give me your true and correct name and date of birth. I'll check it in the system and if it comes back valid, I'll release you with a citation. Or I will take you to jail. It could take three weeks to process you.'"

"Within a minute," the man said he was Brian David Mitchell and provided his correct date of birth, Randell said. The officer cited Mitchell and released him.

Jeremy Clarke served a Mormon mission in San Diego, Calif., from 2001-03. In December 2008, he met Mitchell, who identified himself as "Peter" at the time, in a Lakeside, Calif., wardhouse.

Mitchell's hair was "done up" and he was wearing nice clothes. Mitchell said he was a non-member "investigating" the church at the time. One night, Clarke was going to eat dinner at the home of Virl Kemp, whose daughter prosecutors say Mitchell plotted to kidnap. The Kemp family saw Mitchell walking along the road and invited him to dinner.

After dinner that night, Clarke tried to teach Mitchell about the LDS Church, its beliefs and its prophets. "I don't remember there being much of a reaction," Clarke said. During the conversation, Mitchell seemed religious but reserved. He never proclaimed to be a prophet or talk about his own beliefs, Clarke said.

A California woman testified that she encountered Mitchell on a rainy day in March 2003 in a parking lot at Lake Dixon outside Escondido with a woman and a girl who was wearing a gray wig and sunglasses.

Rebecca Braaten said she offered the trio a ride back to town and the three seated themselves in the back of her car, forcing her cousin and friend — men who were 6 feet tall — to share the front passenger seat. She joked that because there were six people and five seatbelts that she shouldn't drop the hitchhikers off at the police station.

"The defendant's response was a nervous laugh," Braaten said.

During the 20-minute ride, Mitchell controlled the conversation, asking typical questions such as where they lived and where they worked, she said. When she asked the girl questions about her age and where she went to school, she never answered, Braaten said.

"There was a brief pause and then the defendant would provide the answer to the question," she said.

Mitchell said he was a missionary, his name was Peter and the girl's name was Augustina, she said. He volunteered that the girl was his daughter from a previous marriage, which Braaten did not believe because the two had different coloring and did not appear to be genetically related.

She also became suspicious because the girl was wearing sunglasses on a rainy day. In addition, Mitchell claimed he was from Kittery, Maine — a town she had visited with her family almost every year on the holidays when she was growing up — but was unfamiliar with the restaurants and stores, such as the L.L. Bean outlet, Braaten testified.

"By that point, I was very uncomfortable with the situation and I did want them to be out of my car," she said.

Braaten dropped the three off at an exit close to Escondido. She had to work that evening so she asked her friend to go online to check for missing children and went to a police station to check herself the next day. She was told that the police didn't have an online missing children database, she said.

North Las Vegas police officer Craig Adair was patrolling the city's south side on the afternoon of March 11, 2003, when he was called out to a Burger King to check on three suspicious people.

He spotted them at an intersection near the restaurant. Mitchell, Barzee and Smart were in street clothes. Smart had on a wig. Mitchell told Adair his name was Peter Marshall and said he did not have any identification with him.

Mitchell said he was preaching and began reciting something, possibly scripture, before Adair cut him off with another question.

"Every sentence the man said made some reference to Jesus or God," according to Adair's report of the incident, which defense attorneys read in court. Adair said Mitchell was calm and polite, even as Adair told him he was investigating a reported kidnapping. Mitchell said Elizabeth was his daughter and he cooperated with police.

Police held up a photograph of the missing child from Michigan against Smart's face. It did not match, and the three continued on their way.

Troy Rasmussen was working as a Sandy police officer in March 2003, when he received a report of some suspicious people walking on State Street near 10000 South.

He wasn't getting answers from the women because Mitchell kept fielding all the questions. So Rasmussen separated the group.

"I observed him become agitated," said Rasmussen, now a Cottonwood Heights police officer. "He started talking to me. He became nervous. He was concerned what the other two girls were doing."

Mitchell tried to inch closer to Rasmussen as he spoke with Smart.

"When we first questioned him, he was in preacher mode. He would talk in biblical sayings, telling me he worked for God. He had no identification. He gave up his earthly name and his positions," Rasmussen testified. "When he was separated, he talked more on a normal encounter basis, as you would with a normal police officer talking to somebody."

The officer said he did not believe Mitchell was mentally ill. Rasmussen said Mitchell was "coherent" and would "only seem to go into this prophet persona when he was cornered."

"I took it as a smokescreen to hide the truth," Rasmussen said of Mitchell's biblical talk. "He wouldn't use it when I was alone with him. It was like he was going in and out of character."

When Rasmussen suggested the girl was Elizabeth Smart — "The gig is up. We know who she is." — Mitchell "tried to intimidate me with his body language. He gave me a look like ... an 'F. You' type look toward me."

Defense attorney Wendy Lewis zeroed-in on details of Rasmussen's involvement in the arrest, including whether he put the handcuffs on Mitchell and where Mitchell and Smart stood. Lewis pointed out that Rasmussen's report lacked nearly all of the details he testified to Monday.

Leslie Miles, who was a psychiatric nurse practitioner at the Utah State Hospital when Mitchell was under evaluation there, said she believes he was not psychotic and that he was able to control his behavior when he wanted to.

When he first arrived, Mitchell sang and later used charades to communicate with the staff, she said. However, he stopped after one request, she said.

Miles described Mitchell as self-centered.

"Mr. Mitchell functioned very well," Miles said. "He could get his needs met. He was not psychotic."

She once observed him lining up enough patients to agree to turn the channel to "Charmed," a television program he liked, Miles said.

She also testified that Mitchell appeared to turn his belief system on when his treatment team was around. Mitchell expressed concern about her salvation, but didn't go into preaching spiels and never told her he was a prophet or destined to fight the Antichrist, according to Miles.

Miles testified she has seen numerous patients with religious delusions — "I've met Jesus many times," she said — and Mitchell did not seem compelled to share his ideas as they did.

She also said, "My opinion is, when I saw him he was not mentally ill."

Tye Jensen, a psychiatric technician at the Utah State Hospital when Mitchell arrived in the fall of 2005, testified he and Mitchell talked "freely" and often, but seldom did conversations focus on religion.

They would talk about books, television and Jensen's schoolwork, although Mitchell tended to dominate the conversations.

"They were almost refreshing," he said. "I could hold a deeper level of conversation with him than I could with any other patient on the unit."

At one point, a conversation between another psychiatric technician and a patient with whom Mitchell was close caused Mitchell to stop talking for about eight months, communicating only through notes. Mitchell began talking again when the patient became frustrated and yelled at him to talk.

Judith Fuchs, a Utah State Hospital psychiatric technician, said Mitchell would be "front and center" when "Charmed" came on. He claimed to be a strict vegan, she said, but ate pork.

She referred to Mitchell as sneaky and a liar, saying he took food from other patients' trays.

One day, after Mitchell got removed from court for disrupting proceedings by singing, he came up to her as soon as she arrived at work and asked her if she was going to the library that week, Fuchs said.

"He was supposed to be this ranting, raving lunatic" but was asking about books, she said.

Psychiatric technician David Talley said he asked Mitchell why he sang in court and Mitchell replied that he was not going to be judged by man.

"I said, 'You know you'll be thrown out.' He said, 'Yes, absolutely,'" Talley said.

Another time, he heard Mitchell describe to another patient the staffing patterns, when shifts changes occurred and which hallways could not be seen by cameras, he said.

Outside court, Talley said Mitchell is very much in control of his actions.

Mitchell exercises, sleeps and occasionally sings in the room where he has watched his trial over the past month, according to the man who has escorted Mitchell to and from court for the past year.

Dennis Durando, a deputy with the U.S. Marshal's Service, said Mitchell sometimes rolls up tissue paper and sticks it in his ears "as ear plugs and lays down on the bench" to sleep.

During Barzee's testimony, Mitchell's demeanor changed.

"He was very attentive," Durando said. "He stood as close to the monitor as he possibly could and didn't move. He was very still."

Durando was not asked about Mitchell's behavior during Smart's testimony.

Rarely does Mitchell sing when he is not in the courtroom, he said.

Durando said Mitchell begins singing when he reaches the door behind the jury box and continues until he has to be removed from court. He stops once he arrives in the room where he watches the trial.

One morning before the trial, Mitchell entered a mostly empty courtroom and stopped singing until someone other than his defense counsel and court employees were there, Durando said.