This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Nine Mile Canyon • Once threatened by industry, this eastern Utah chasm's archaeological splendor now has a corporate partner and a new chance at preservation.

An energy company drilling for natural gas above Nine Mile Canyon is offering up to $5 million in grants to help study, protect and promote thousands of rock-art panels and long-abandoned American Indian sites.

Denver-based Bill Barrett Corp., which previously reached a compromise with environmentalists and archaeologists to use the canyon road to reach its West Tavaputs Plateau well field, this week announced the grant program to assist in protection.

The grants are open to any applicants who can prove to peer reviewers that they have a valid academic, educational or preservation project. It's a new payoff for the cooperation that previously spawned a deal to shrink the company's West Tavaputs drilling zone while mandating effective dust control on the canyon access road to protect petroglyphs from an obscuring — and potentially corroding — dirt blanket.

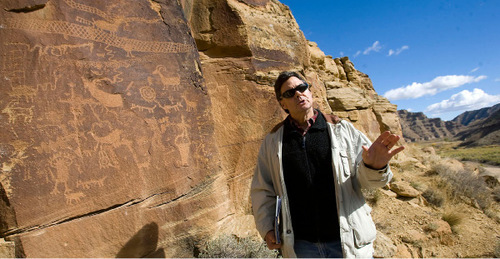

"It's unprecedented in state history," said Jerry Spangler, an archaeologist studying the evidence of Fremont and ancestral Ute occupation among the rock bands between Price and the Green River.

The federal government has pumped big money into archaeological digs such as Glen Canyon before construction of the dam, but always as a prelude to destruction, said Spangler, executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance. Barrett's money will aid both study and preservation.

Nine Mile Canyon, misnamed by mapmakers, is a roughly 50-mile gallery of ancient etchings.

The company has already created a $250,000 grant pool and will offer $5,000 more for each new well it drills in the next few years — potentially topping out around $5 million.

Spangler expects the canyon — a mix of ranches, oil company holdings and rocky, scrubby U.S. Bureau of Land Management hills — to be Utah's most-studied archaeological trove during the coming decade, thanks to the grants. Sites on cliffs well away from the road are well-preserved and could hold compelling secrets about life through the millennia.

He showed off an example of the canyon's 10,000 or so sites Tuesday — a sandstone panel that centers on a chiseled owl but also depicts bighorn sheep, humanoids and other forms of life. The panel needs a management plan because, while relatively unknown until recently posted on the Internet, people now traipse across private land to reach it. Left to its own, it could be scarred by vandals the way other sites near the road have been for decades.

Down the road, there are signs of public access on another rock face near a staging area where Barrett has stacked drilling pipe. People have scratched or hammered initials and dates during the past century, right next to snakes and deer tapped out by artists of 1,000 years ago. At another site, a divot in the center of a human figure's torso is evidence that someone on the road sighted in a small-caliber rifle and squeezed off a shot for the ages.

Vandalism prevention is part of the reason for Barrett's grants. Company spokesman Jim Felton said the work that archaeologists do here will help develop management plans on public and private lands. In some places, that will mean limiting access to ancient treasures. In others, it will mean increasing exposure and adding educational kiosks. A state or local tourism board might apply for money, he said.

The expense is minor compared with the $1 billion Barrett intends to invest in its development, or the $6.5 billion it expects to extract in gas. But Felton said it's the kind of gesture that comes with cooperation among developers and interest groups.

"Listening sure beats litigation," he said.

The company's latest dust-suppression efforts, using a nontoxic pine resin on the road, appears to be protecting the petroglyphs, Spangler said. On fully exposed panels, rain has washed away dust that accumulated from previous truck traffic. Under overhanging rocks, some panels remain coated and probably won't ever be exposed unless archaeologists decide it's appropriate to wash them.

Despite the successes, there is an undeniable dilemma created by the gas development. Years ago, the canyon road was too rough for leisurely sedan travel, and few people ventured here. Now cars and trucks buzz through routinely. It means thousands more people have the chance to admire the rock art — or spoil it.

Flint Lahmann, a German with a summer home near Vernal and a seasonal yearning for American Indian history, traveled the road and photographed petroglyphs Tuesday. He said the smooth, wide dirt road is unrecognizable as the trail he first drove 25 years ago.

"It's better now," he said, "but I think that's not good. Too many people."

Spangler is of two minds about the increased access. It gives more people the opportunity for mischief, he said. But it's also possible that getting more eyes into the canyon will force visitors to behave.

He looks forward to placards drawing attention to the blight of vandalism.

"It's educational, as much as anything," Spangler said, "because people walk up there and say, 'Man, who would do that?' "

There is some evidence that growing education campaigns are helping. Fewer etchings in the rocks carry dates from recent decades. Among about 500 archaeological sites inventoried so far, Spangler said, only two vandals have marked a date since 2000.

Archaeology grants

• Up to $5 million for study, preservation and promotion of Nine Mile Canyon archaeological sites.

• Available to nonprofit, university, government or other researchers or tourism promoters.

• For application information, call Jim Felton at 303-312-8103, Scot Donato at 303-312-8191, or e-mail sdonato@billbarrett corp.com.