This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

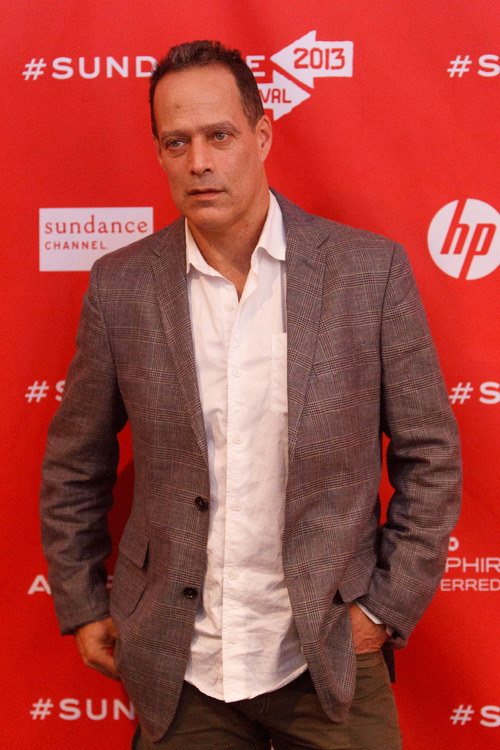

In 2011, after their Afghanistan war documentary "Restrepo" was nominated for an Academy Award, photographer Tim Hetherington and writer Sebastian Junger were briefly embedded in a very different kind of place: Hollywood.

Attending the Oscars was perhaps as otherworldly as watching young soldiers sleeping in combat zones. "People who makes films generally aren't in combat," Junger says. "People who are in combat generally don't make films."

That heady trip made what happened next, Hetherington's death from mortar fire while reporting on the Libyan civil war, even more tragic.

Hetherington's work was lauded for its humane vision, for the photographer's ability to capture human stories that undercut and deepened viewers' perceptions of war. A tribute to that vision unfolds in Junger's intimate new film, "Which Way Is the Front Line from Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington," screening this week at Sundance in the Documentary Premieres program.

The documentary takes advantage of hours of videotaped interviews with Hetherington as he and Junger were promoting "Restrepo," which won the Grand Jury Prize in the documentary competition at Sundance three years ago.

Over the course of 10 years, Hetherington, who was mostly self-trained as a photographer, had successfully moved into documentary filmmaking. In a phone interview, Junger, the author of The Perfect Storm and War, talked about the singular vision of his friend and colleague, as well as the nobility of the work of war reporting. After the film's Sundance launch, it will air on HBO in April.

Why did you make this documentary in the first place?

I wanted to remember and honor Tim's life and his work and his humanity and his courage. He had this idea he was working on in Libya, how young men see themselves in combat and how they emulate the news images and from Hollywood. He called it the "theater of war." I wanted to bring that idea into public view.

How did you begin to make the documentary?

It came in stages. I organized a memorial for Tim in May — three weeks after he died. Some of the journalists who were with him in the attack (while covering the civil war in Misrata, Libya) and knew him well were coming to New York for the memorial. I had a lot of questions about how he died. Then I thought I should record the interviews, and if I was going to record them, I should videotape them properly in the studio.

One of the things that deepen the documentary is the video footage of Hetherington talking about his work. How did you have that kind of access?

We were very lucky. The timing was horrific in some ways. We had just been at the Academy Awards with a documentary about war. When it happened, when Tim died, all of those interviews he did to support the movie were suddenly available to us.

In the video interviews in the documentary, Hetherington was expressing his doubts about continuing to report from war zones.

I recognize that debate from within myself. He was 40. He had taken a lot of chances. He was starting to wonder if it was time to leave the poker table, but he didn't leave the poker table in time. The war kind of depressed him, being exposed to violence like that. He had a pretty decent case of PTSD. He didn't talk about it like that, but I saw the effects of it, of what has come to be called "moral injury."

What sets apart Hetherington's approach to war photography?

It's very easy, if you're a war reporter, to think if there's no shooting going on, there's nothing to report. It's a very narrow way to think. Tim wasn't necessarily interested in combat. What he was interested in was how young men relate to each other, and how they act in moments of great stress, like combat. And actually, the lulls in between combat are very stressful.

In the documentary, you talk about Hetherington's photographs of sleeping soldiers, 19-year-olds looking like 12-year-olds, made for "Restrepo." What distinguishes those images for you?

He was recording something that is absolutely essential to the combat experience, which is everyone is exhausted and can fall asleep everywhere. Exhausted sleep is part of combat. Tim thought to remember that. That morning he created one of the great documents of the War on Terror.

What do you mean by that? 'One of the great documents of the War on Terror'?

I feel like the image of the War on Terror is so clichéd, and very tinted by people's political views. Many Americans see soldiers as righteous heroes, very morally black and white. Others think morally black and white in the other direction, that we shouldn't be there. The truth of the matter is war is a lot of things: Very violent, very everything, very tiring, very fulfilling.

What do you hope to accomplish with this film?

I hope it will have an impact on public conversation. I think about war. I think about the Arab Spring, and the dangers of war reporting, and the specific extraordinariness of one guy who died way too young.

Beyond war reporting

"Which Way is the Front Line From Here? The Life and Times of Tim Hetherington" is screening in the Documentary Premieres category at the Sundance Film Festival.

Wednesday, Jan. 23, 9 p.m. • Egyptian Theatre, Park City

Friday, Jan. 25, 3:30 p.m. • Redstone Cinema 1, Park City

Saturday, Jan. 26, 6:45 p.m. • Broadway Centre Cinema 3, Salt Lake City

More • The documentary is scheduled to air on HBO in April.

Also • In response to Hetherington's death, filmmaker and writer Sebastain Junger launched a nonprofit called RISC — Reporters Instructed in Savings Colleagues — to provide free emergency medical training to freelance journalists. "Tim's wounds were not necessarily fatal, but he could not get to help in time, and he bled out," Junger said. "I realized if I had been with him, I could not have saved his life. Like most war reporters, I know almost nothing about battlefield medicine. Most of the war reporting done now is by freelancers, brave people who head into combat and hope for the best."

Info • http://www.risctraining.org

—

Tim Hetherington: Photographs from Afghanistan and Liberia

Hetherington's work will be on exhibit in Park City through Jan. 30.

Where • Julie Nester Gallery, 1280 Iron Horse Dr., Park City; 435-649-4893