This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

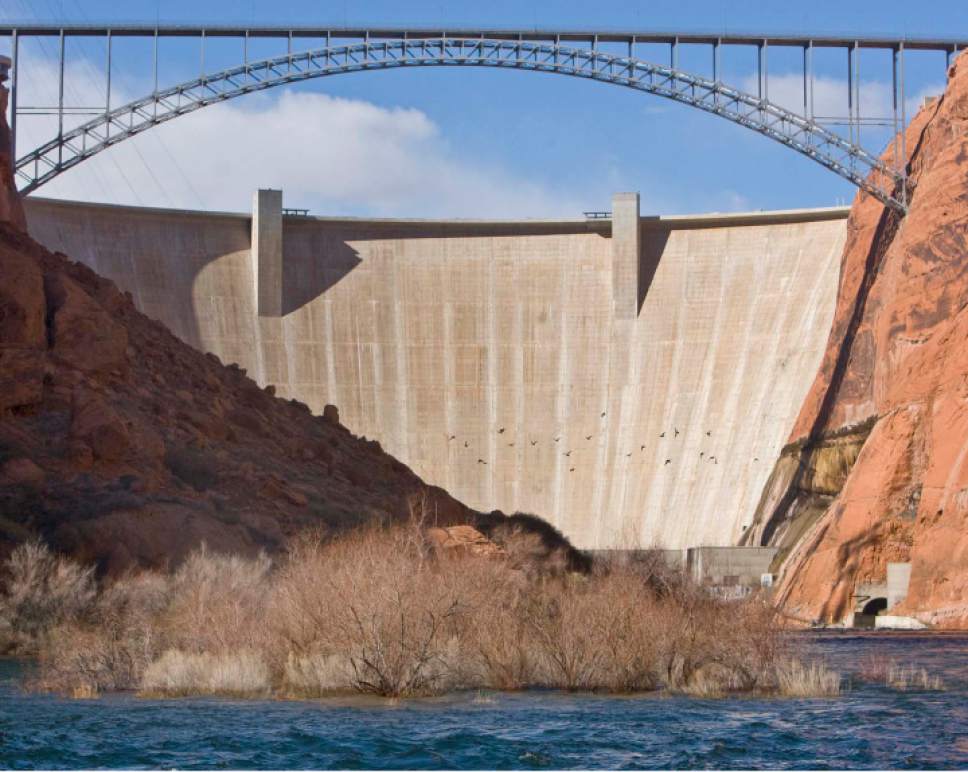

On her way out the door, Interior Secretary Sally Jewell has signed off on an agreement to "adaptively manage" the Glen Canyon Dam and Utah's Lake Powell for the next 20 years.

The agreement, which follows a previous 20-year plan approved in 1996, gives some certainty to those who rely on the dam and lake, but that word "adaptively" is a sign that the future isn't getting easier to predict. Like most baby boomers, the 53-year-old dam isn't facing its own mortality — yet.

The agreement ensures the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will continue to provide water and hydropower from the dam, and it has provisions to continue dam releases intended to more closely mimic natural conditions to protect the ecosystem below the dam, including protected fish species. The agreement comes after a years-long process involving 15 federal agencies, seven states and the Navajo Nation.

"I applaud the diverse set of partners that came together to develop a plan that will deliver water and power from Glen Canyon Dam, while also protecting the incredible natural and cultural resources that call the Colorado River Basin home," Jewell said.

Environmental groups have called the agreement a waste. They want the dam removed, arguing that it and the lake are destructive to nature and inefficient for water storage. Rep. Rob Bishop, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, doesn't like the agreement, either, saying it favors fish protection over hydropower users.

The Bureau of Reclamation, which has been building and managing western water projects for almost a century, isn't buying either side. The dam will be structurally and environmentally sound for decades to come, the bureau says, and the loss of hydropower under the new agreement will be less than 1 percent, a small price to pay for improving the ecosystem.

A major presence in Utah's tourism portfolio, Lake Powell faces major challenges. It hasn't filled for years because of drier climate, and it loses millions of gallons through evaporation and porous sandstone. Some have argued the water is better stored downstream in Lake Mead, but that has tradeoffs, too. The rock is less porous there, meaning less seepage, but the desert heat is higher, leading to more evaporation.

Adaptability in the agreement is about two things: First, the effects of dam releases are still being learned, so new variations are still possible to protect the downstream environment. And, second, the climate is changing. The agreement does not predict the specific effect of climate change, but it must manage the change that comes.

Given all that, 20 years is a reasonable timeline. Here's betting the next 20-year agreement will need to be even more adaptive.