This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

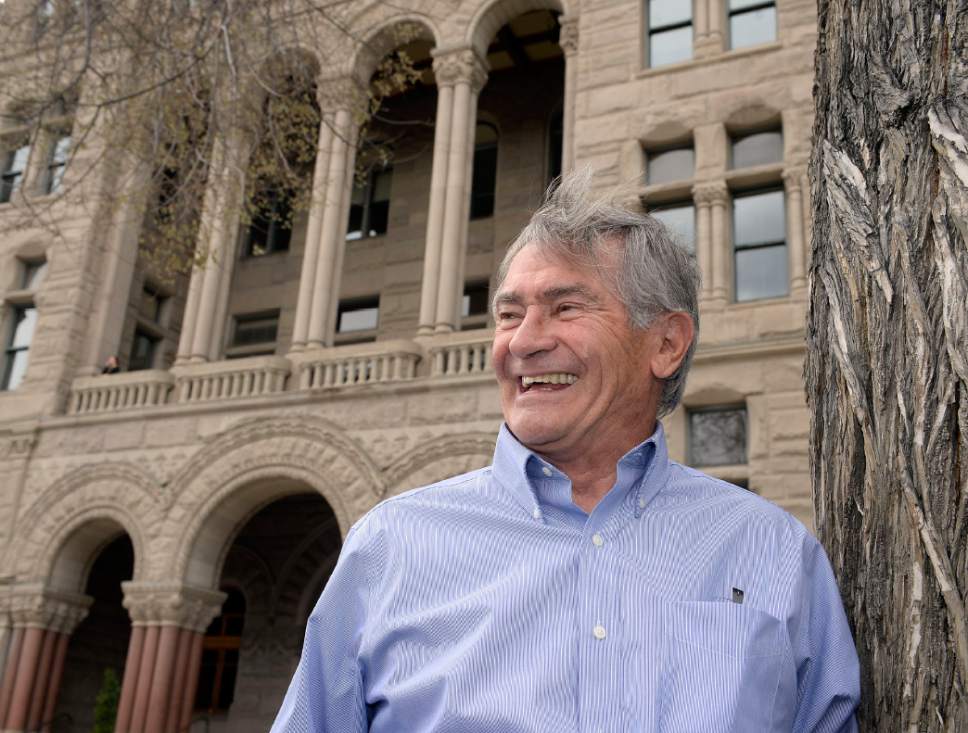

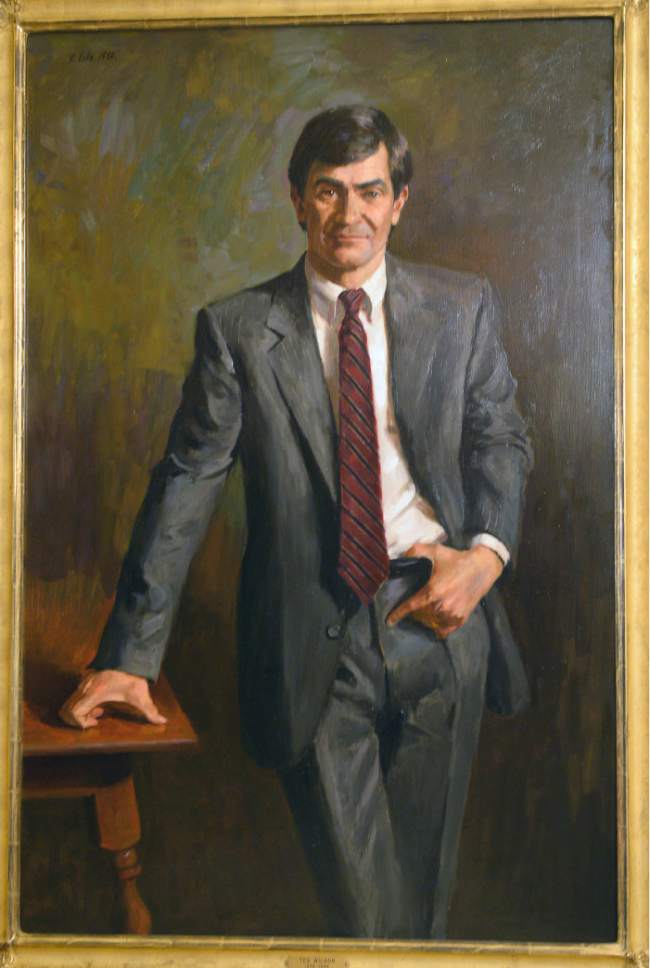

The elevator door slides open on the third floor of City Hall and there stands a relaxed but confident Ted Wilson, the only three-term mayor in the modern history of Salt Lake City.

He wasn't quite as old then — the portrait was completed 35 years ago. But Wilson still wears that easygoing smile and strides with a sure-footed step.

He has been a mountain climber, a teacher, a politician, an environmentalist and more. Now, at 76, he says he's retiring — for real. Some who have known the energetic and affable Wilson may find that hard to believe.

"He is a Renaissance man," said Palmer DePaulis, Wilson's hand-picked successor and the capital city's 31st mayor. "He thinks, he reads, he's fun to be around. It's contagious."

Wilson was the last mayor of Salt Lake City's five-member commission government and became the first mayor when it morphed into a strong mayor/council structure. The upheaval came amid a scandal, dubbed Citygate, where commissioners attempted to usurp power from the mayor's office.

Wilson had first been elected mayor in 1975, and then ran for the new chief executive spot in 1977, as voters sought a change of structure at City Hall.

Wilson was an incredibly popular mayor, said Tim Chambless, who worked for him and is now a professor of political science at the University of Utah and also is affiliated with the Hinckley Institute of Politics. Chambless conceded that he isn't objective when it comes to his old boss and friend.

"He brought a youthful enthusiasm to city government and a sense of cooperation and congeniality," Chambless said. "I look back on those days and see Ted Wilson as an outstanding mayor."

By most accounts, Wilson and the new council, which included DePaulis, soon righted City Hall. For his part, Wilson recalls his contribution with humility.

"You come to the realization that you don't know how to do everything. But you could put the right people in the right places," he said. "Until you learn that you depend on everyone around you — until you learn that — you won't do very well."

Wilson, a Democrat, will be remembered for many things. He ran an unsuccessful campaign against Sen. Orrin Hatch in 1982. In 1988, Wilson had a huge lead in polls over incumbent Republican Gov. Norm Bangerter. only to lose the election. Merrill Cook also ran in that race as an independent.

That defeat was stinging but Wilson took it in stride.

"I've always said to myself, that if you have to hatch out better things for yourself through public office, you're in it for the wrong reasons," he said. "If you can't retreat back to where you were before, you've cheated reason."

For many, Wilson will be remembered for his leadership in late spring of 1983, when a heavy late snowfall on top of a formidable snowpack gave way to a heat wave that unleashed flooding that turned City Creek into a roiling, brown monster.

On May 28 of that year the city hydrologist predicted City Creek would exceed capacity, leading to drastic flooding. The next day, Wilson called LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball and leaders of other church denominations to request volunteers. By 7:30 p.m. that evening. sandbag dikes were completed from Memory Grove to 400 South just as City Creek came raging down into the valley.

—

The early years • By the time Wilson graduated from Salt Lake City's South High School in 1957, he already was hooked on climbing and skiing. He also earned a bachelor's degree in political science at the University of Utah and, eventually, a master's degree in education from the University of Washington.

He married his sweetheart, Kathryn Carling, in 1962 and, in 1964, took a job teaching at the Leysin American School in Switzerland. He also ran the ski program there. They had just had the first of five children.

"My wife put up with a lot from me," he recalled, "because I did a lot of skiing and climbing."

After a year, the young family returned to Utah where Wilson began teaching at Skyline High and worked as a summer ranger at Grand Teton National Park.

In the summer of 1967, he and a half-dozen others rescued a climber with a broken leg on the north face of the Grand Teton. "We spent three days on the face," Wilson remembered. "At the time it was the most technical rescue in North America."

In 2012, his daughter, Jenny Wilson, who sits on the Salt Lake County Council, made a documentary of the rescue. It played on more than 100 PBS stations.

Wilson got his political feet wet in 1972, when he joined Wayne Owens' campaign for Congress. Owens won and he appointed Wilson as his administrative assistant.

"It was exciting and scary," Wilson said. "My boss was on the House Judiciary Committee investigating [President Richard] Nixon."

In 1974, Owens ran for the U.S. Senate against then-Salt Lake City Mayor Jake Garn. But Owens was tied down with the Nixon investigation in the nation's capital and sent Wilson around the state to campaign for him and, in several cases, to act as his surrogate in debates with Garn, the Republican.

"After one debate, Garn told me he would win the Senate race — and then I should run for mayor," Wilson recalled.

Garn was right on both counts. Owens lost and Wilson ran for mayor the next year, serving until July 1, 1985, when he left the post mid-term to become the director of the Hinckley Institute of Politics at the University of Utah.

It was a move he almost didn't make.

"It was my dream job because, at heart, I'm a teacher," he said.

But he felt he couldn't leave the mayor's chair in mid-term, although the political "fire was no longer in my belly."

"I told Kathy I got the Hinckley job but had to turn it down."

Eventually, he was convinced by friends and family to change his mind.

Wilson stayed at the Hinckley Institute until 2003 (taking a leave to run for governor). His 18-year tenure there broadened the program's vision and substance, said former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson.

"He built up the Hinckley Institute to expose countless students, including my son, to experiences that changed their lives," Anderson said.

During that period, Wilson also was an assistant professor of political science at the U. Among other things, he taught a class in Indian government, which included taking students on a three-week trip to India. During one week of the outing, students helped construct a school for poor residents.

Sheena McFarland, a one-time Wilson student and former Tribune reporter, recalled that he was accessible and dedicated.

"Ted was really engaged and wanted his students to have a full understanding of how government worked in India," she said. The trip "was really exciting. He was a great teacher, but he also was a wonderful guide into a new culture."

After his long marriage to Kathy ended, Wilson married former Tribune columnist Holly Mullen in 2004.

—

The environmentalist • Wilson also had his hands in community and environmental issues. He did a stint as executive director of the Utah Rivers Council, where he successfully fought to protect 165 miles of the Virgin River in southern Utah as a Wild and Scenic River. He also championed the right of anglers and other outdoor enthusiasts to have access to waterways flowing through private property.

In 2009, Utah Gov. Gary Herbert, a Republican, appointed Democrat Wilson as his environmental adviser.

"He's someone who brought a lot of cachet and could build consensus between sides," Herbert said. "He listens and can bring people together. His background is one of practicality."

Wilson later took a position with Talisker Corp., which owned and operated The Canyons resort in Summit County. There, he advocated for a controversial tram into Big Cottonwood Canyon that brought criticism from the environmental and ski communities.

Some accused him of selling out.

"I think there were a lot of people who felt Ted's environmental credentials were being used by a corporation that was intent on environmental damage," Anderson said.

That allegation still brings a furrowed brow to Wilson. "I really got criticized," he said. "My ski buddies went crazy. I was attacking the canyon."

Wilson explained, however, that he was trying to save Big Cottonwood Canyon from automobile traffic by providing an alternative access route.

"There is nothing harder than having a good idea 10 years ahead of its time," he said.

Wilson's latest position has been the director of UCAIR — the Utah Clean Air partnership — a program that encourages Utahns to voluntarily reduce air pollution. It began as a state program, but has since become a private nonprofit.

Whether it's leading a city into a new era or losing an important political race, Wilson moves on without bitterness or remorse.

Those who know him say he's always gracious and forward looking. It's his style and has won him many admirers.

Ted Wilson

• Salt Lake City mayor — 1976-1985

• U.S. Senate candidate — 1982

• Gubernatorial candidate — 1988

• Director of the Hinckley Institute of Politics — 1985-2003

• Environmental adviser to Herbert — 2009-2011

• Talisker Corp. governmental relations — 2011-2013

• UCair director — 2013-2017