This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

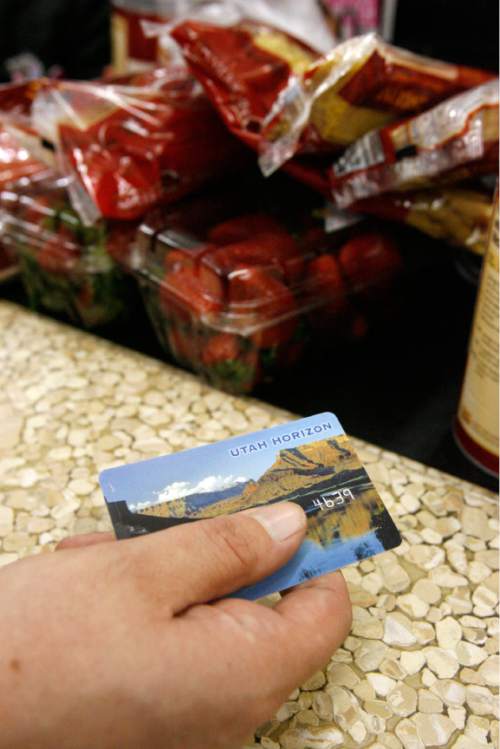

As Utah's economy improves and more people find jobs, the number of residents receiving food stamps has declined — just not very fast.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, it may take most of the next decade for the state to revert to the levels seen before the collapse. As it stands, 234,500 residents still receive federal support to buy food (it was 130,000 back in 2007) and the percentage of children in the program has jumped from 48.6 percent in 2007 to 53.4 percent in January, indicating that families have had a harder time escaping poverty.

"It is definitely the case that this Great Recession has been so much different, the effect so much larger," said Carrie Mayne, chief economist for the Utah Department of Workforce Services.

And yet the trend lines are all moving in the right direction. More than 41,000 people have dropped off the food-stamp rolls since 2011. The percentage of recipients who work has risen to nearly 39 percent, and among those still receiving help, the average assistance has declined from $303 per month in 2011 to $285 in January 2015.

Economists expect some lag between the decline in food-stamp recipients and economic growth. Those on the lower end of the income scale are often among the first laid off, and when the economy rebounds they are not the first rehired.

"The people who are going to be the first re-entrants into employment are going to be the most employable," Mayne said. "You tend to see those with fewer work skills, those who have been experiencing poverty, to be the later ones to experience the benefits in the growth of the economy."

This recession resulted in high numbers of long-term unemployed and underemployed people, wages that have stayed flat and workers who have left the labor force altogether. As a result, Gina Cornia, executive director of Utahns Against Hunger, says it's easy to see why food-stamp rolls are expected to remain inflated for years to come.

"The economy just doesn't work the same for poor people," she said. "They face greater challenges in providing for their families."

When an economy starts to recover, employers have plenty of prospects to pick from, so there's little pressure to offer higher pay. It's only when fewer people are unemployed and the pickings are slim that companies increase wages. While that has yet to happen, Utah has seen its housing become more expensive as the population continues to grow.

"All of those things just conspire against people who are just not earning enough money," Cornia said. "Your food budget is the one that has the most flexibility in it."

In January, 38.8 percent of the families receiving food stamps had at least one member employed, a figure that has ticked up every year since the economy hit its nadir in 2011.

It's been easier for younger adult Utahns, 18 to 29, to transition off food stamps. This group accounts for nearly two-thirds of the reduction among adults in the program. Older working-age adults have seen some improvement, while the number of senior citizens receiving food stamps has climbed, which Mayne attributes to the aging of the population.

The Census Bureau reported in late January that one in five children nationwide receives food stamps. In Utah, the rate is one in seven.

To be eligible for food stamps, a person or a family must make 130 percent of the federal poverty level or less. For a family of four, that is $2,584 per month before any taxes or deductions are taken out. For able-bodied adults without children, they can receive food stamps only for three months out of every three years unless they work or are in a training program for 20 hours per week.

Nationally, the food-stamp program cost $74 billion in 2014, double the outlay in 2008. Republicans in Washington, including Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, have argued that it's time to create new work requirements to nudge people off the program.

"Ultimately," he said, "the purpose of the social-safety net — and so the goal of any welfare reform — should be to make poverty temporary, not just tolerable."

Cornia is skeptical of such changes, saying she doesn't see any widespread reluctance on the part of poor Utahns to improve their situation and she believes the approach discounts the problem of low wages.

"What do we do with those folks who are working and just can't make it?" she asks.

While Congress debates structural reforms, 10 states will use federal grants to try to reduce their food-stamp rolls. In Georgia, participants would create an online work plan, while California is testing a new child-care program, according to The Associated Press.

The Congressional Budget Office predicts that, as things stand, the nation won't see food-stamp rolls fall to the level they were before the Great Recession until 2025.

Utah's government produces no such projections and with the state's economic growth, it's safe to assume the Beehive State would beat the national average. Even so, it will still take years, possibly into the 2020s, to achieve the pre-recession mark.

mcanham@sltrib.com Twitter: @mattcanham