This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The health care coverage that many low-income Utahns would get under the plan advanced by the House on Friday may be the insurance equivalent of a Yugo, sponsor Majority Leader Jim Dunnigan acknowledged.

"But it still drives," the Taylorsville Republican said, arguing for his HB446, Utah Cares, before a House committee.

The ride, however, is nowhere near as sweet as that enjoyed by the more than 90 percent of Utah lawmakers who take the health insurance offered to them as part-time state employees.

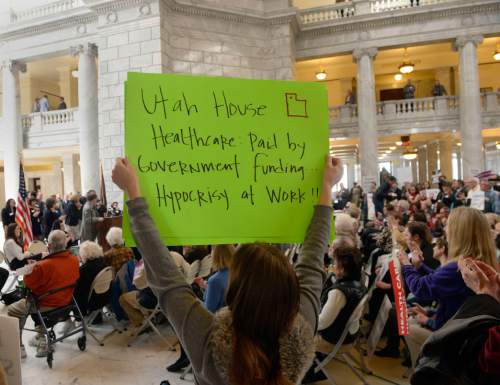

It's a point advocates of the governor's more generous — but jeopardized — Healthy Utah plan are making as the end of the session looms without a decision on Medicaid expansion.

Utah legislators, as part-time state workers, are eligible for a package of benefits that includes the health insurance offered to other state employees, including highway patrol officers, motor vehicles clerks and wildlife resource officers.

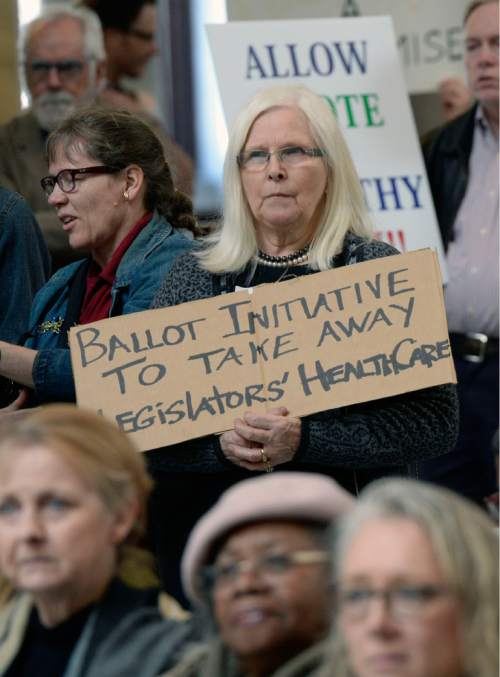

Under legislation tweaked several times over the years, retired lawmakers also are eligible for medical coverage, depending on when they retire and how many years they have served in the Legislature. Lawmakers who were elected before 2012 and have served 10 years or more can have 100 percent of their health insurance costs covered by taxpayers — for life.

The House and Senate denied The Salt Lake Tribune's open-records requests for documents explaining members' insurance benefits and declined to say how many and which lawmakers participate.

The state's Public Employees Health Program declined to provide an exact number or the names of lawmakers who participate, citing the federal health care privacy act, HIPAA.

PEHP did say, however, that year in and year out, more than 90 percent of the 104 lawmakers take one of the insurance plans offered to state employees. And it provided information about the plans.

As soon as they take office, legislators qualify for the same three plans as other state employees, including all permanent full-timers and some part-timers who work at least 20 hours a week.

The plans are called Traditional, STAR and Utah Basic Plus, and each has two tiers — distinguished by which network of doctors and hospitals the employee wants to use. STAR and the high-deductible Utah Basic Plus offer tiers that require no monthly premium payments from employees.

Of the state's 23,300 employees, 18,900 take one of the plans.

And whichever route lawmakers choose — Healthy Utah, which would cover 89,000 Utahns; or Utah Cares, which proposes to expand coverage to half that number — their own insurance is pretty deluxe, said Sen. Luz Escamilla, D-Salt Lake City.

"It is shameful for all of us who have the best health care coverage in the state, which is PEHP, to talk about people who do not have coverage and think that's OK," she said when the Senate was debating a Medicaid expansion bill.

Indeed, Dunnigan himself, an insurance agency owner, said lawmakers' health care insurance is "probably gold," just under the most premium plans, regarded as "platinum."

While lawmakers pay pretty much the going market rates for co-pays, deductibles and their share for routine medical services — 20 to 30 percent in most cases — they can opt for plans that cost nothing until they seek medical care. Those plans — STAR and Utah Basic Plus — have zero premiums when a lawmaker chooses the Summit or Advantage networks.

Summit plans use University of Utah, MountainStar and IASIS doctors and hospitals; Advantage plan users go to Intermountain Healthcare. Employees who want access to both networks pay a premium.

The premium for a lawmaker with a family choosing the Traditional plan with either network is $58 every two weeks. If they want access to both networks of hospitals and doctors, they pay $239 bi-weekly.

The state also kicks in taxpayer dollars to help cover lawmakers' insurance costs — with the tab ranging from $377 to $518 every other week for families on the various plans. And it tucks a contribution into health savings accounts for participants on STAR and Utah Basic Plus plans.

Dental plans can cost a lawmaker with a family $4.59 to $17.77 every two weeks, and vision plans run from $6.29 to $9.04 bi-weekly.

All of the lawmakers' health insurance plans allow them to see specialists, be treated in hospitals and go to an emergency room. They also get routine coverage of pregnancy, mental health, heart disease and cancer.

There are extra perks in the state plans: allergy serums, chiropractic treatment, infertility consultations and up to $4,000 for adoptions.

That can't be said for the state's Primary Care Network (PCN), which Dunnigan's Utah Cares plan would expand to enroll 24,500 more poor people.

PCN, essentially a bare-bones plan for the relatively healthy, already covers 18,000 on a first-come, first-served basis.

Its low-income participants pay no premiums and can visit a doctor for $3, or get up to four prescriptions a month for $3 each. Emergency room visits for true emergencies are free, as are diabetes products, birth control and mammograms. A PCN participant can get a free ambulance ride, free eye exams and dental exams, and even cavities filled for free. But a participant can't get a pair of eyeglasses or a colonoscopy, and is out of luck if he or she gets sick — the network does not cover specialists or hospital care.

As Brook Carlisle of the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network said, "You can find out you have cancer. ... But you can't treat it.

"I don't know if I'd rather know or not," said Carlisle.

PCN is known among doctors as the acronym for "Pretty Crappy Network," the executive director of the Utah Academy for Family Physicians told a House committee last week.

In addition to enrolling more Utahns in PCN, Utah Cares would expand Medicaid to 22,000 more people. More deluxe than PCN but still no Cadillac, Medicaid has low co-payments and allows people to get treatment when they are sick. But it's not the best at providing preventive care.

Dunnigan's plan would expand coverage by allowing adults without children to qualify for Medicaid if they make less than 34 percent of the poverty level and adults with children if they make less than 65 percent of poverty.

Healthy Utah would offer Medicaid to qualifying Utahns who chose it, and most low-income Utahns would get help paying for the premiums of insurance offered by their employers or help buying private insurance in the marketplace.

Healthy Utah would cover 89,000 Utahns next budget year, while Utah Cares would extend coverage to 44,500 not now covered.

With four days left in the session, the Senate has to decide whether to try to marry the two plans, do nothing and see if the governor calls a special session on Healthy Utah, or jump on board the Utah Cares train.

Westminster student Stacy Stanford said Utah Cares would be of limited help to her. She uses a wheelchair due to a degenerative neurological disorder, the result of a car accident five years ago.

Stanford falls in the coverage gap that Utah Cares strives to fill — not qualifying for Medicaid because she doesn't have children and making too little to get subsidized private health insurance on the federal government's marketplace.

Stanford figures she would be covered by PCN under Dunnigan's plan, but it would do her little good.

She still would not be able to go to a neurologist or get the tests to determine the nature of her disorder. She's called 15 such specialists, and the cheapest offer for a first visit was $500, which she hasn't been able to afford.

And the drugs? Said Stanford: "Four prescriptions a month is nothing for someone with a chronic condition."

Stanford has nine. —

House and Senate balk at disclosure

The Salt Lake Tribune made open-records requests to the House and Senate for documents explaining the "health insurance coverage for representatives, including the cost of plans and coverage levels."

Both houses denied the requests, saying they have "no records that are responsive," and said they "do not prepare, own or maintain documents explaining such coverage." The Senate suggested contacting PEHP, the Public Employees Health Program.

PEHP, a division of Utah Retirement Systems, provided that information.

The Tribune also requested data "showing how many representatives participate" in the state plan, and the names of those who do. Both houses denied the request, saying those records are private and not subject to disclosure.

PEHP said disclosure would violate the federal health care privacy act known as HIPAA. It added that it's up to the employer — in this case, the Legislature — to consider such a disclosure request. PEHP said it is exempt from the state's Government Records Access and Management Act (GRAMA).

The Tribune also asked for the rules that describe when former members are able to continue receiving state-provided health care. Both houses said they had "no records responsive to your request," and referred the Tribune to the state code.