This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

To me, Bob Bennett was a giant of a man — and I don't just mean intellectually.

At 6-foot-6, my mother's youngest brother — who was described in one Watergate book as Sleepy Hollow's Ichabod Crane — towered over my 5-foot-2 frame. Hugs were a tad awkward between his stooping and my reaching.

But he never talked down to me, not even on subjects on which we disagreed. He asked my opinion about religion, writing and journalism. On several occasions he invited me to critique his words or offer feedback.

When I was a young woman, I was fascinated by reports that my playful and entertaining uncle was the infamous "Deep Throat," Bob Woodward's super-secret source in "All the President's Men." I collected stacks of newspaper clippings and books naming Bob, a public relations professional in D.C. at the time, as the source. So I asked Bob point-blank, and he vehemently denied it, laughing at the suggestion.

He was appalled at how many journalists — including at least one at my paper — continued to believe it, despite all the evidence to the contrary, until former FBI agent Mark Felt was unveiled as the real Deep Throat.

The experience, though, made Bob skeptical of many claims of certainty, including those by neighbors of Mormon founder Joseph Smith that the young visionary was a fraud.

My loquacious uncle was an LDS believer but able to balance faith with realism. He wore his Mormon pedigree lightly (descended from a prophet and two Salt Lake City mayors), but he saw his church leaders as kin, full of both inspiration as well as foibles.

He also was passionate about finding political solutions to urgent national and global problems.

In the early 1990s, when our baby daughter Camille was repeatedly hospitalized with congenital heart disease, my husband had to quit working to care for her because our primary insurance came from my job. Bob and I talked endlessly about U.S. health care, how insurance was tied to employment and how families can be decimated by rising medical costs.

He listened carefully to my woes, agonized with us, and, later, when he crafted a bipartisan Senate heath care bill, one of its key elements was splitting insurance from employment.

When Camille died in 1994 and we were saddled with $65,000 in unpaid bills, Bob mourned with us and then quietly gave us a sizable donation to help pay down our debts.

That's back when he was considered one of the Senate's millionaires, having built a small fortune marketing day planners and time-management workshops.

But Bob was never a typical man of wealth.

He cared nothing for expensive clothes, homes, furniture or cars (the lanky Republican was one of the first senators in D.C. to buy a hybrid Honda, having to fold his long legs under the steering wheel of the tiny two-door sedan) and his generosity knew no bounds.

A couple of years ago, I was in Washington for a wedding and needed a place to stay. Bob picked me up from the airport and drove me around the nation's capital to the various festivities — all the while regaling me with hilarious tales from his courting days, especially about several unsuccessful marriage attempts until, at age 29, he finally found his wife, Joyce.

Bob was a born storyteller (Joyce sometimes would roll her eyes when he started an oft-repeated narrative), speaking at length and off the cuff, occasionally making himself the punch line. His midcentury home in Salt Lake City's Avenues and his town house near Arlington, Va., were magnets for me and my cousins — some staying for months at a time. We longed to get his behind-the-scenes scoops on Washington or hear what really happened in the Senate cloakroom, where so many deals were struck.

In 2008, I called Bob and asked if my family could have tickets for the first Obama inauguration. After he said, "sure," I then asked, without hesitation, "Can we stay with you, too?"

The night before the ceremony, Bob had three dinner invitations — from Utah Republicans, national Republications and Vice President-elect Joe Biden. He went to the latter.

Biden, a Catholic, and Bob, a Mormon, had many shared values and a lot of mutual respect, my uncle told me. In his speech that night, Biden pointed to his longtime Utah friend and said Bob's presence was a symbol of the administration's hope for the future.

We all know how that turned out — for both of them.

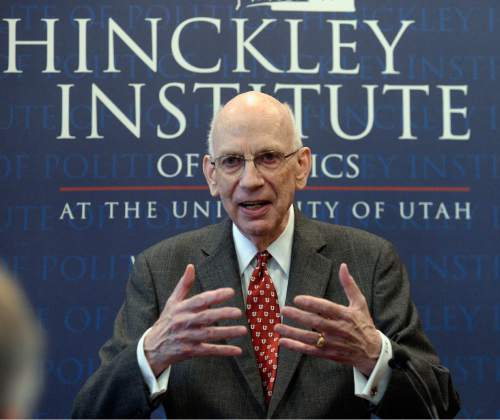

In January, the Hinckley Institute of Politics at the University of Utah inducted Bob into its Hall of Fame.

With a brief respite from the cancer that would ultimately take his life, Bob was in great form that day. Standing tall and energized, he waxed eloquent about the value of a two-party system, one side trumpeting the value of the free market and the other the importance of central government. Both are needed; each offers an important corrective for the other. Compromise helps both — and, in the end, all of us.

That was a conversation he and I had so many times as we argued about political assumptions and approaches.

Earlier that day, former Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt noted that Bob's temperament was a key to success as a politician. Leavitt had never seen my uncle lose his temper, not even in a heated political battle.

I realized that I, too, had never seen him angry — or easily offended or void of optimism — in all our years together.

About two weeks ago, I was chatting with him and he shared his ideas for improving Mormon PR, which he hoped to live long enough to implement.

"That should give me leverage with God," my dying but ebullient uncle said with a grin I could hear through the phone, "don't you think?"