This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It's been common sense and a basic principle of science: We get half of our genetic makeup from each of our parents.

But scientists from the University of Utah have found that that isn't always true — some cells in the brain choose to express one parent's genetic information over the other, and such preferential treatment could be linked to vulnerability for mental illnesses.

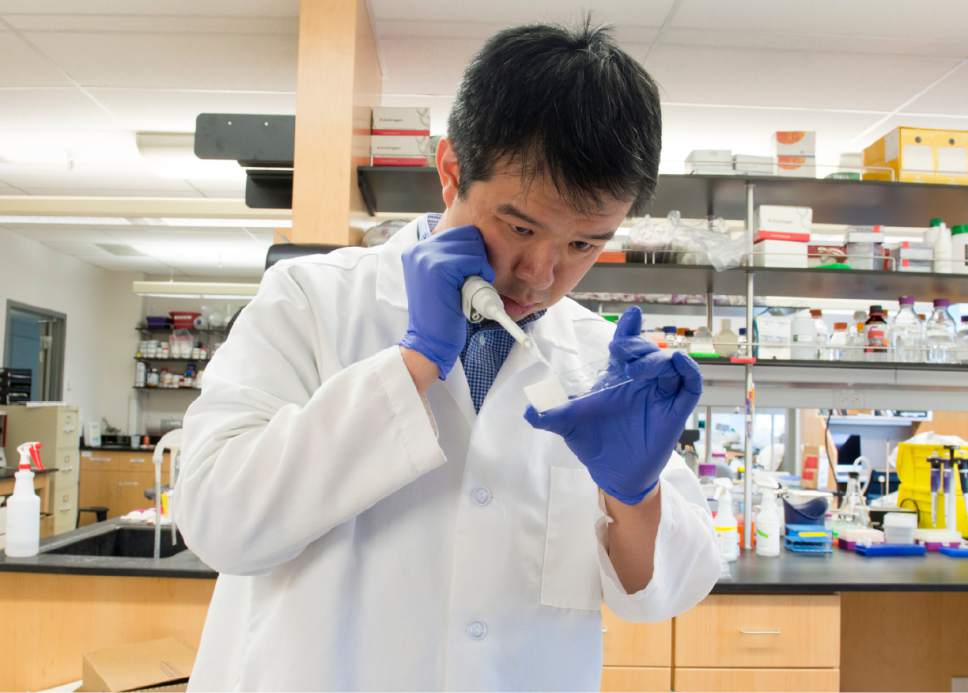

Researcher Christopher Gregg and his team discovered 200 genes in the mouse brain that always activate the DNA inherited from a single parent, showing a preference for either the mother's or father's gene. Typically, cells have switches that activate both parents' genes.

Gregg, an assistant professor of neurobiology and anatomy, wondered whether any cells in humans showed the same bias — and how they might influence risk for mental illnesses, such as autism, schizophrenia and depression.

After four years of work, Gregg and his team have found such biased cells in primates and humans and developed unexpected information about how they work.

"The results present a different picture of genetics that we didn't know about if it weren't for these genes," Gregg said.

Among their findings: Some cells with a maternal or paternal preference choose mutated gene copies rather than dominant or healthy ones. In some cases, they silence a healthy copy from the disfavored parent.

Having two active copies of a gene normally provides protection in case one copy is defective,

Brain cells that prefer mutated genes may contribute to brain disorders, Gregg said. The research provides a new path toward understanding how mental illness occurs and may help discover new ways to treat it, he said.

"What we are now working toward is being able to better predict how mutations in the genome from mom and dad can shape risk for mental illness," Gregg said. "We are interested in discovering mechanisms that could provide an opportunity for a new gene therapy where you can switch on healthy gene copies that are silenced in the brain."

In a new study published online in Neuron in February, Gregg's team described brain cells in primates playing favorites with genes linked to Huntington's Disease, schizophrenia, attention deficit disorder and bipolar disorder. In humans, they showed brain cells preferring gene copies associated with autism and intellectual disability.

The researchers also revealed that these cells can change that preference, later switching to the other parent or activating DNA from both.

For example, in at least one region of a newborn mouse's brain, about 85 percent of the genes activated by cells were solely maternal or paternal gene copies. Ten days later, the cells were expressing all but 10 percent of the genes equally.

The region secretes serotonin, a chemical associated with mood.

The team also pinpointed cells in other regions of the body that prefer one parent's genes, including in muscles and in the liver. Gregg said his team is expanding into how preferential expression by cells could be linked to cancer and autoimmune diseases.

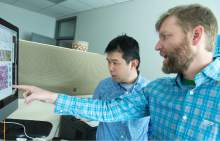

Monica Vetter, chair of the U.'s neurobiology and anatomy department, said Gregg's results are fundamental to providing new insight into brain development.

"The research changes how we think about understanding and treating human disease," she said. "His work is important to the department because it's linking research to important clinical problems and hopefully shows how scientific discoveries like this are important in diagnosing and treating illness and disease in the future."