This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

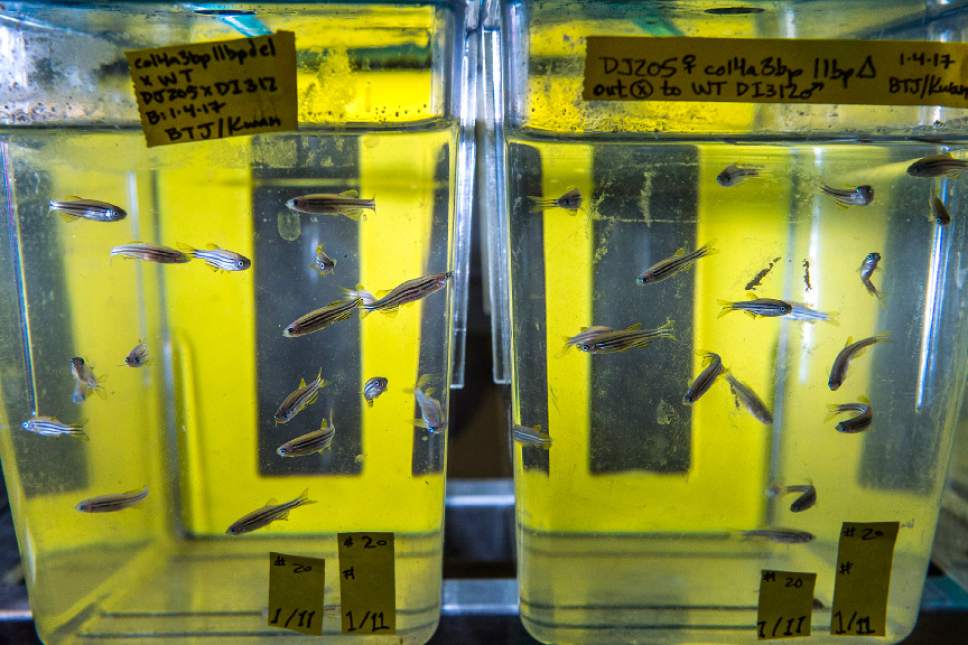

At 5 days old, zebrafish are just tiny black specks barely visible through squinted eyes pressed close to their plastic container of a home.

That size makes them perfect for University of Utah experiments in drug development: After the fish are given a gene mutation associated with a disease, such as cancer, only a tiny amount of any drug under investigation is needed to see side effects.

Randall Peterson, dean of the U.'s pharmacy school, and others conduct dozens of drug studies using zebrafish, he said, to find potentially helpful treatments for health and mental problems ranging from anemia to heart failure and even autism. He's also tested potential cyanide antidotes for counter-terrorism efforts.

Projects such as these largely are possible because of funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Between 2012 and 2016, U. researchers received about $744 million in NIH funding for various research projects. That funding accounts for roughly 40 percent of the U.'s funded awards each year.

"We have had some wonderful philanthropic support and industry support," Peterson said, " ... [but] we would be in real trouble without [NIH] help."

The future of NIH funding, however, is far from certain under President Donald Trump's administration. In the proposed federal budget Trump released Thursday, funding for the National Institutes of Health would be cut by 20 percent, or nearly $6 billion.

It remains unclear how the proposed cuts might impact scientific research at the U. and across the country.

In January, Trump asked current NIH Director Francis Collins to remain in his position, but the president last year also told conservative radio host Michael Savage that he had heard "terrible" things about the organization.

Though federal research funding is now uncertain, Vivian Lee, dean of the U. School of Medicine, has said the NIH has bipartisan support in Congress.

Yelena Wu, an assistant professor in the U.'s Department of Family and Preventive Medicine and an associate member of the Huntsman Cancer Institute's cancer control and population sciences program, and her collaborators rely on NIH funding to conduct her melanoma studies.

It's important, Wu said, because of the high rate of melanoma in the Beehive State. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no state has a higher melanoma rate as of 2013.

She has been teaching families at high risk for melanoma how to prevent the disease, Wu said, particularly in their children. In fall 2016, she video-chatted with three separate families every couple of weeks to discuss preventive measures — such as when and what type of sunscreen to wear. The participants also wore a UV exposure monitor to determine how tan their skin is over time.

"Our goal is sort of a combination of minimizing kids' UV exposure and getting them to engage in these behaviors, like sunscreen use and then, ultimately, whether they actually get sunburns," Wu said. "We'd like to lower the likelihood of [high risk] children getting melanoma."

She plans to try these video chats again this year, she said, this time expanding the number of participants.

But NIH funding is critical to that goal, she added.

"Without this funding, it would make it difficult for me to spend this much time on this kind of work, which is what it requires," Wu said. "It is so, so key."

Twitter @alexdstuckey