This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When a child comes home with lice or a cough appears in the middle of the night, the thought of making a trip to the emergency room — and paying the exorbitant cost associated with it — can be daunting.

But Utahns with the internet and a smartphone, computer or tablet now have several cheaper options, thanks to telemedicine.

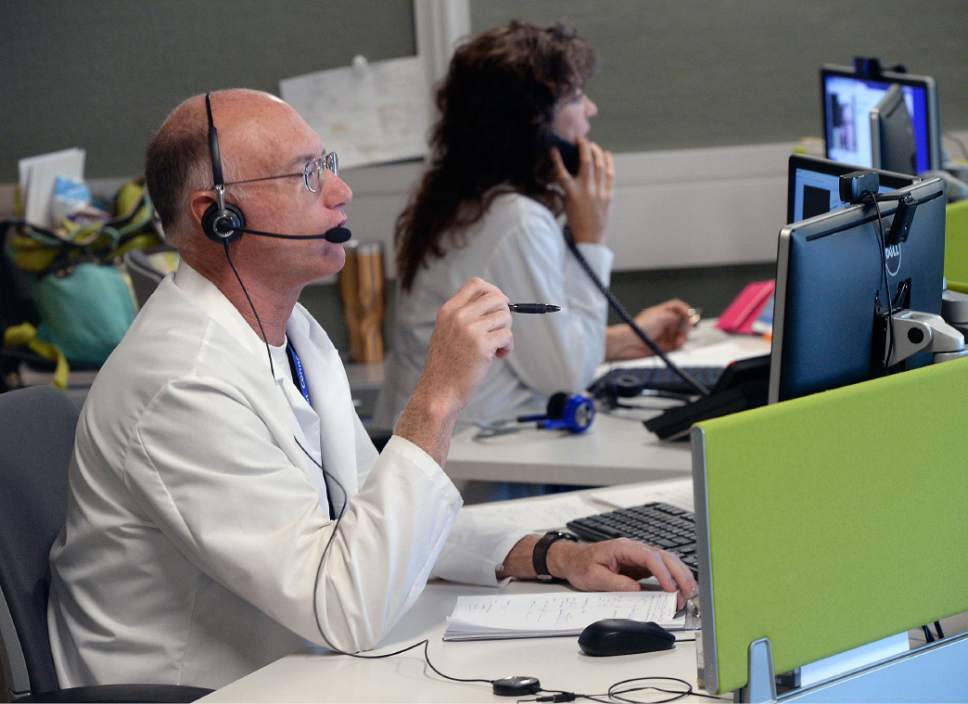

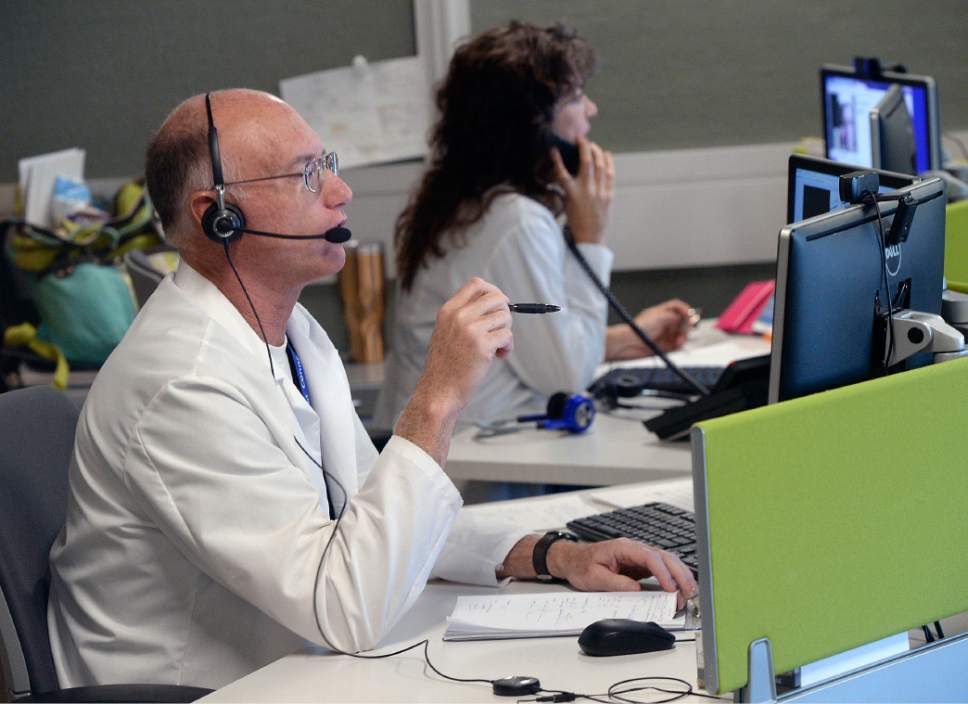

Both University of Utah Health Care and Intermountain Healthcare started primary care telemedicine programs this year, which allow a person to, essentially, video-chat with a doctor about an ailment. That doctor can then make a diagnosis, issue an online prescription or inform the individual that an in-person visit is needed.

"If we can remove 50 percent of the people taking time off work and arranging for child care so they can sit in the waiting room to just receive a diagnosis to wait it out ... it just makes the health care system more efficient," said Nate Gladwell, director of the U.'s telehealth program.

Telemedicine was just one area examined by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University when it recently ranked Utah fifth in the country for health care openness and access.

Center researchers used nearly 40 indicators to rank the states. Other areas examined include pharmaceutical access and public health.

"We consider these rankings to be meaningful and useful, but we stress in the strongest of terms that they are not definitive and final," researchers wrote. "These rankings should begin conversations, not end them."

—

Telemedicine

Though both the U. and Intermountain started their primary care telemedicine programs this year, they vary slightly.

At the U., there are 10 emergency room providers who rotate being on call for virtual primary care visits. Utahns can call 801-213-UNOW between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. seven days a week.

It takes an average of seven to eight minutes to connect to a physician, Gladwell said.

Spanish translators are available through this service, and Gladwell said the hospital plans to roll out more language services in 2017.

At Intermountain, providers are available 24/7 to patients who download the Connect Care application. It typically takes less than five minutes to connect to a physician. Currently, the service only is offered in English, but Brian Wayling, assistant vice president for Intermountain's TeleHealth Services, said the system wants to get translation services online next year.

Slightly problematic is that only some insurance companies cover these virtual visits at both systems, but the cash fee is less than $50.

The service is good for things like coughs and colds, lice, urinary tract infections or some rashes, for example. But it is up to each individual physician to determine whether a more through, in-person examination is necessary, Gladwell said.

Both systems also offer telehealth services for specialized areas such as stroke, intensive care and burns. This allows clinicians in rural areas across the state to conference with a specialist from the U. or Intermountain for help on a case, saving the patient time, distance and money.

That, typically, is covered by insurance.

—

Pharmaceutical access

Researchers also examined an area that has been fairly contentious in Utah for several years: access to medical marijuana.

State lawmakers tried to legalize medical marijuana earlier this year, but the proposal to permit full-plant cannabis use failed in the legislative session's final hours when they found there was no money to implement the program.

As of November, 28 states and Washington, D.C., have legalized medical marijuana in some way, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Utah lawmakers did, however, pass a law in 2014 that allows Utahns with severe epilepsy to import whole-plant cannabidiol extracts from states where medical marijuana is legal.

Under that law, the Utah Department of Health issues hemp extract registration cards to qualified individuals. From July 2014 to October 2016, 166 cards were issued, according to a recent department report.

With the help of $40,000 from the state, the U. will conduct a study analyzing individuals with these cards. The U. is projected to complete the study by February 2018, said Rich Oborn, the department's office of vital statistics director, at a legislative hearing last month.

But several lawmakers intend to try again in 2017 to legalize medical marijuana.

This summer and fall, individuals have proposed measures that would allow for more research on the drug as well as allow medical marijuana to be used for various types of conditions. Another proposal would create a regulatory framework for medical marijuana if and when it becomes legal.

Rep. Brad Daw, R-Orem, will push the research measure in the Legislature next year, a move that's important because he says other states have seen negative outcomes — medical marijuana being used as a stepping stone to recreational use, for example.

"I find that very disturbing," Daw said at a meeting last month. "That's why I propose we start our adventure with cannabis in Utah" with studies.

—

Public health

Jennifer Plumb, medical director for Utah Naloxone, sees a state in dire straights.

It's ranked fourth in the nation for drug overdose deaths and in 2015, there were 268 prescription opioid overdose deaths and 127 deaths due to illicit opioids, including heroin.

That's why she says access to naloxone — also an area examined by center researcher — is so important. Naloxone is a medication that can reverse the effects of an overdose if taken within 10 minutes.

Concerned family members, friends and others have been able to legally obtain naloxone since 2014, but just last week state officials made access even easier. Pharmacies can now hand out the medication without a prescription.

"I'm hopeful this will really empower pharmacists ... to say to their clients, 'I've been taking care of you for a long time, I want to talk to you about a reversal agent,' " Plumb said.

Utah Naloxone has handed out about 4,300 naloxone kits since July 2015, with 175 reported overdose reversals. Plumb's organization, largely funded through grant money, gives away the kits for free.

Naloxone kits typically are covered by insurance, she said, but the price can range from $45 to $150 for people who do not have insurance. There is one type of kit that costs $4,500 and verbally gives you instructions to administer the product, she added, but it doesn't necessarily work any better than other kits.

Now that pharmacies can hand out the medication without a prescription, she said she hopes they don't limit what is offered to the $4,500 talking kit.

"I advocate for everyone to have a kit on hand: we are all at risk of witnessing an overdose," she said. "It doesn't imply anything, just that you're willing to be prepared to help someone who may need you."

Twitter @alexdstuckey —

Utah health care access

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University ranked states based on access to health care and providers' freedom. Here's how Utah ranked:

Telemedicine: 20th

Pharmaceutical access, such as medical marijuana: 9th

Public health, such as access to naloxone: 43rd

Corporate: 1st

Direct primary care: 6th

Insurance: 27th

Medical liability: 8th

Occupational regulation: 28th

Provider regulation: 16th

Taxation: 18th