This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ella Johnson doesn't remember exactly how many ACT tests she has taken.

"I think I took it a total of six times," the Davis High senior said.

But Johnson does remember her scores. She started with a 28 and got better with each attempt.

The final time she took the test, however many times that was, she earned a 36 — the highest possible score on the college-readiness exam.

"I just knew I could do better if I kept trying," she said. "I didn't want to quit before I knew I'd done my best."

Johnson was one of 15 Utah high school students who earned a perfect score on the ACT this school year — an achievement level met by less than a tenth of 1 percent of students nationally, according to ACT administrators.

ACT perfection remains rare, but is becoming increasingly more common in Utah.

A single member of the class of 2009 earned a 36 on the ACT — out of 23,229 Utahns who took the test. Last year, when 35,074 students took the exam, 17 claimed a top score.

At one time, a 36 could virtually guarantee a full-ride scholarship to a good school. But the meaning of a perfect score may be slipping as more and more test takers top out and colleges move to a less-structured assessment of student abilities.

For their part, ACT administrators figure there's nothing wrong with the test. They have no plans to make it harder or adjust the scoring.

"We would love it if everybody got a 36," said Ed Colby, ACT public relations director. "The ACT is not graded on a curve in any way."

Still, if everyone racked up a 36, it would likely mean the end of the ACT as a college admissions tool, according to Matthew López, director of the Office of Admissions at the University of Utah.

"Before you see a world of 36," he said, "we're going to see schools not using the ACT in the same way they use it now."

Try, try again • Many Utah 36ers didn't achieve perfection on their first try. They took the test repeatedly until they reached the top score.

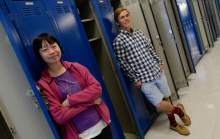

Hans Lehnardt, one of three students at Skyline High who notched a 36 on the ACT this year, took the test four times.

The senior, who will leave for a Mormon mission in Madagascar next month before enrolling at LDS Church-owned Brigham Young University, said he studied for roughly an hour before his final test attempt.

"I knew I could do it," he said. "And my brother got a 36."

His tip for acing the test: chewing gum.

"It gets blood flowing to your head and to your brain," Lehnardt said.

Juncen "Amy" Wang, a junior at Skyline, started taking the exam in eighth grade, when she scored a 30 during a talent search program.

When she took the test again this year, she earned a 36.

Wang said she is looking out of state for universities. She's interested in computer science or linguistics but also hopes to continue studying piano, which she has played for 12 years.

"I really enjoy it," she said. "It would be kind of a pity to just drop it after high school."

Despite the bump in Utah's number of perfect scorers, Colby said the nation's performance on the ACT is fairly consistent. Overall scores of a state such as Utah, he noted, are better judged by averages than a dip or a surge in the pool of top scorers.

"Those can vary year to year without necessarily representing a trend."

In 2014, Utah's high school graduates scored an average of 20.8 on the ACT — the best performance among the 12 states that tested all seniors, so-called "full participation" states.

Utah's average score has increased each year since 2012, when testing of all seniors started. The state's rising scores mirror the way individual students tend to improve on repeat attempts at the ACT.

That type of micro- and macro-improvement over time is common with testing systems, according to Jo Ellen Shaeffer, director of assessments and accountability for the Utah Office of Education.

"Any time you have a large-scale assessment," she said, "it's sort of a natural process over time that kids end up doing better and better every year."

While some are determined to up their scores, López said students shouldn't take the ACT ad infinitum in pursuit of perfection.

There's value, he said, in taking the exam at least twice, because first-time jitters can hinder performance. But the ACT, like the game horseshoes, has value even if students fall slightly short of their target.

"The college-admissions process is stressful enough as it is," López said. "Stressing over an ACT the third, fourth or fifth time is probably not going to get the return on investment that you would expect."

Nationwide, a "college ready" score on the ACT is between an 18 and a 23, depending on the test subject — well below the flawless 36.

Colby said a perfect score isn't a guarantee of college and university success, but instead indicates that a student is well-prepared for the first year of higher education.

"They may not succeed," he said. "But this says they are ready from an academic standpoint."

And López said the median ACT test score for half the students at the U. ranges from a 23 to a 27. A quarter of students score higher, a quarter lower.

"We don't have a minimum, per se," he said, "but once you get into the 18s and below, that's where we're a little bit worried about remediation requirements."

Tomorrow's test • ACT administrators are starting to implement a new, computer-based version of the exam. About 6,000 students nationwide took the computerized test in April and early May.

But Utah education managers say the transition to digital remains several years out in the state.

While the new test is available as an option for full-participation states, including Utah, Shaeffer said a computer-based ACT would interfere with other state assessments and strain school resources.

"It was just never really a conversation for Utah to do that," she said. "Trying to get all kids on a computer on the same day at the same time might be problematic."

Colby said students shouldn't worry about which format they see on test day. The computer-based ACT is designed as a digital copy of the paper-and-pencil exam.

Even on a computer, "a 25 means exactly the same thing as a 25," he said. "We don't want to change the content, and we don't want to do anything that's going to impact the scores themselves."

Colby said there are no plans to make a more-challenging ACT if students achieve scores of 30 or better.

"We love to see the average get higher and higher, because it means college and career readiness is improving," he said. "That's our goal."

López credits population growth in Utah for the uptick in top scorers. At the same time, U. admissions staffers have not noticed any significant change in prospective students' overall ACT scores.

The U. recently implemented a "holistic" admissions process, which favors individual student qualifications over test- and grade-based formulas.

He said ACT scores remain among the top five factors considered by schools, but admissions officers also are instructed to look at extracurricular activities and the relative difficulty of students' high school course loads.

"We really look for students taking advantage of the opportunities that were available to them," López said.

Utahns traditionally have favored the ACT over the rival SAT, which is seen by many as the primary exam for East Coast and elite universities.

But Colby said SAT exclusivity among the Ivy League is a misperception, and all of the nation's four-year schools now accept ACT scores as a measure of college readiness.

"It's no longer an issue," he said. "The last holdout itself was probably five or six years ago."

Meanwhile, the quest for a perfect 36 continues among Utah students.

Dale Schlachter, another Utah ACT top scorer and a junior at Hillcrest High, said he might apply to an Ivy League school, but would likely stay in state at either BYU or the U.

Even though he has a perfect 36 under his belt, Schlachter said he's not satisfied with his performance on the optional reading section, which doesn't factor into a student's aggregate score.

"I might take it again," he said, "even though I got a 36."

Schlachter said students should study and get enough sleep before taking the ACT. But last-minute preparations aren't as beneficial as long-term academic habits.

"It's hard to cram for intelligence," he said. "I think it's important to just enjoy learning."