This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

On a frigid Minnesota morning more than a decade ago, Erin Clark got a call that would determine the trajectory of her medical career.

A family had agreed to let Clark, then a second-year resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, observe the birth of their child. The experience, she said, proved nothing short of inspiring.

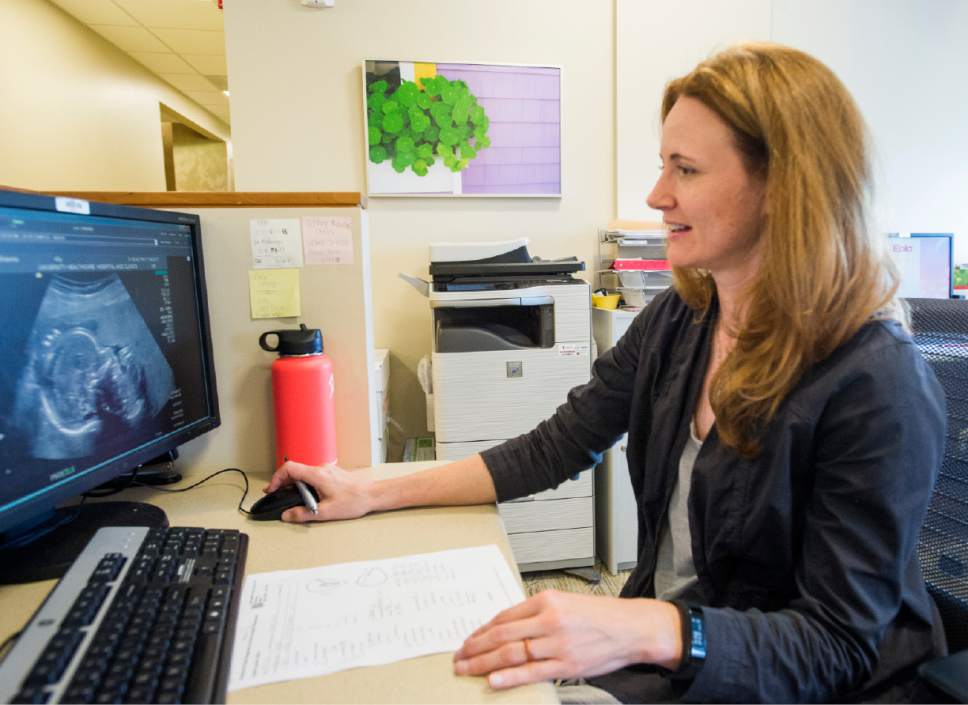

"This baby was just in [the mother] and now it's an independent, living, breathing being," said Clark, now director of the University of Utah's Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. At that moment, Clark, now 40, said she knew obstetrics/gynecology was her specialty of choice.

But a study published Thursday found that the OB-GYN medical specialty is increasingly less popular in Salt Lake City among young doctors. Only 13.73 percent of the city's obstetricians are younger than 40 and many of the others are swiftly approaching retirement age, according to a study conducted by Doximity, a California-based social-media network for medical professionals.

Those metrics, in part, led Doximity to rank Utah's capital among the top 10 U.S. cities nationwide most at risk for an OB-GYN shortage.

Doximity examined data compiled by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as well as self-reported and certification data from 30,000 full-time, board-certified OB-GYNs in the 50 largest metropolitan cities in the country.

Doximity's Utah findings are in keeping with measures indicating an overall physician shortage in the state. With 207.5 physicians per 100,000 population, Utah ranks 43rd in the nation, according to 2015 Association of American Medical Colleges data.

But officials with the three main health care systems in Salt Lake City — the U., Intermountain Healthcare and St. Mark's Hospital — say they are not yet experiencing a significant shortage in OB-GYN specialists.

Some attribute this to the state's high fertility rate — the number of live births per 1,000 girls and women who are between 15 and 44 years old.

The Doximity report found that there were 115.22 births per OB-GYN in Salt Lake City, which is higher than the national average of 105.37. The highest ratio was Riverside, Calif., with 248.05 births per OB-GYN, according to the report.

Eric Rose, vice president of physician recruitment at HCA's Mountain Division, which owns St. Mark's Hospital, said the sheer number of births in Utah attracts OB-GYNs to St. Mark's.

"Utah is the kind of state where there is way more demand. That's one of the things we find that works in our benefit when we talk to and recruit physicians," Rose said. "We don't anticipate a shortfall in patients."

However, officials with all three systems say they've noticed a push among doctors in recent years for more flexible hours.

Clark, who works with residents at the U., said she's detecting some hesitancy among doctors in training to take on the unpredictable, stressful hours that come with delivering babies.

"There is a little bit of burnout" among these specialists, said Bob Silver, chairman of the U.'s OB-GYN department.

And that fatigue is why many OB-GYNs retire earlier than other specialists, beginning at age 59, according to Doximity's report.

In Salt Lake City, the average age of an OB-GYN is 51.59, slightly higher than the national average of 51.39, the study found.

The city's health care systems are working to make hours more palatable for all doctors, but especially the younger ones.

For example, some employ obstetricians who are on-call 24/7 to deliver babies, freeing other OB/GYNs from having to rearrange their schedules or work extended hours when a mom delivers.

"That's helping a lot with the lifestyle," Rose said, "and that's a buzzword we hear time and time again when we're out there recruiting."

These arrangements also makes deliveries safer, Silver said. "There may be a decrease in quality if you have doctors who are working 100 hours a week."

Despite those and other demands from delivering babies, an official with Intermountain said the system hires between five and 10 OB-GYNs each year. And most of those recruits, said Ross Fulton, Intermountain's operations officer of central services, "are young physicians, coming out of their residencies and fellowships."

Clark completed her residency 11 years ago and said she makes sure to stress to new hires that a good work-life balance is essential. She's a runner, she said, and has a family and life at home. But she also has an incredibly fulfilling career.

"Sometimes I'm very tired but I'm never burned out," Clark said. "It's a testament to the fact that you can find something you love and you can make it work."

Twitter @alexdstuckey