This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Given the extreme fire risk, Rep. Mike Noel should be careful running around with his pants on fire.

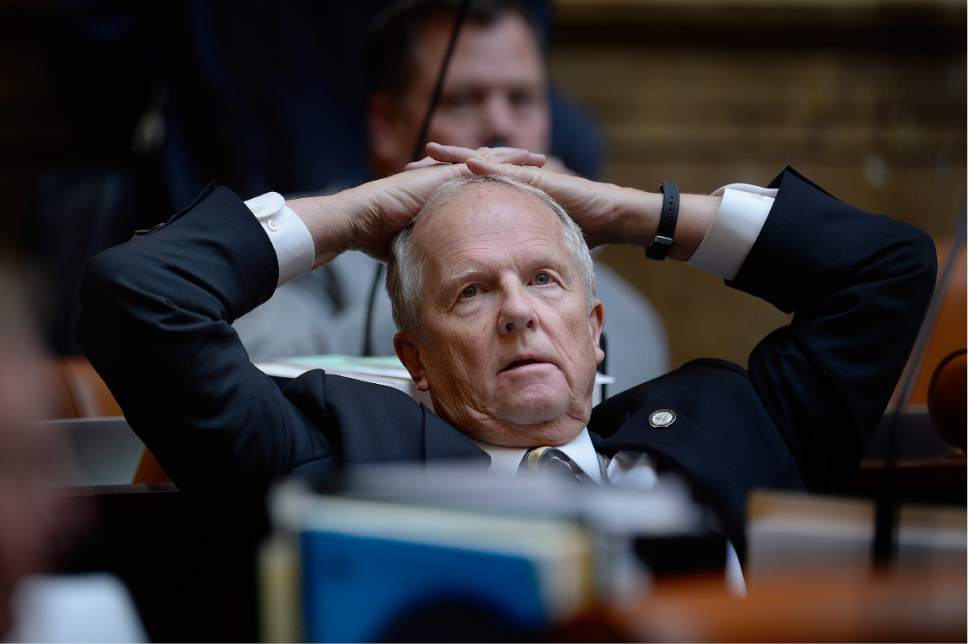

Last week, as flames still threatened seasonal homes near Brian Head, Noel took the opportunity to dish out some inflammatory rhetoric, blaming the wildfire on environmentalists who he says are determined to stop any kind of logging, even if it means watching the forests burn.

"When we turned the Forest Service over to the bird and bunny lovers and the tree-huggers and the rock-lickers, we turned our history over," Noel said at a news conference.

"We're going to lose our watershed and we're going to lose our soils and we're going to lose our wildlife and were going to lose our scenery — the very things you people wanted to protect," the Kanab Republican said. "It's just plain stupidity."

Those rock-lickers, always causing trouble.

The reality, like a forest ecosystem, is a lot more complicated than Noel leads people to believe.

First, the fire Noel is ranting about actually started on private land inside the town of Brian Head, when a resident torching weeds let it get out of hand. It spread from the private land to the nearby state forest and burned on state forest land for three days before it reached the Dixie National Forest.

Second, the timber sale Noel seems to be talking about appears to be the Tippets Valley sale, which was indeed challenged by the group Friends of Dixie National Forest — a group that now is long-defunct. The thing is, Friends of Dixie lost the lawsuit and yet the trees, for more than two decades, still were never cut down.

Something similar happened in the early 1990s, when a bunch of rock-lickers sued to stop a timber sale in the Sydney Valley. They lost, too, but when the trees were offered, nobody bought them.

Overall, though, trees seem to be getting less love and fewer hugs than Noel would have us believe. According to Forest Service data, there has not been a single appeal of a fuels-reduction project in the Dixie National Forest in three years.

There have been just five projects challenged since 2010, and one of those was challenged by the Garfield County Commission. In every instance, the appeal was either rejected or withdrawn.

Even if the dead, beetle-stricken trees had been cut down, it's hard to know if it would have made much difference.

Mike Kuhns is a forestry professor at Utah State University and said when he first came here in the early 1990s, he remembers looking out over large swaths of dead and dying spruce trees in the area. One of his graduate students studied the stands and found them to all be old trees, susceptible to spruce beetle infestations that ultimately ravaged acres and acres of the forest.

If they had logged the area aggressively before the beetle outbreak, Kuhns said, some younger trees would have grown in and there would have perhaps been less dead fuel, but "it's still likely there would have been a major bark beetle outbreak because of the age of the trees, and there may have been fire."

The fire could have been less devastating in that case, Kuhns said, but the old forest was primed for a major change.

Noel's bombastic blame game also distracts from a real and dire threat to forests in Utah and around the West, and that is the reality of the changing climate.

Across the West, the wildfire season is now six weeks longer than it was just a few decades ago and there has been an increase of more than 50 percent in the number of large fires and a threefold jump in the number of "mega fires" that burn 100,000 acres or more.

That's because the average temperature across the West has climbed by nearly two degrees since the 1970s, meaning the snow melts earlier and forests are left hotter and dryer.

It also has put stress on the trees, leaving them less capable of withstanding the bark beetles that have infested millions of acres of forest land all across the West. The milder winters aren't cold enough any more to kill off the pests.

Decades of aggressive fire suppression have compounded the problem by removing the natural cycle of fire and regrowth from the equation.

We need more active management of our forests to remove excess fuels and increase diversity in the forests — both in the types of trees growing and the age of the trees. To do that, forest officials need to be able to do their jobs, without the fear of litigation. But that also means that there needs to be trust on both sides.

Maybe that trust will grow, like a tree, over time, but it is hard to see that happening when you have people like Mike Noel eager to throw firebombs into the tinder-dry forests for the sake of trying to score partisan political points.

Twitter: @RobertGehrke

Editor's Note: This column has been updated to clarify that there have been no appeals of fuel-reduction projects in the Dixie National Forest in three years, and no successful ones in 10 years. The original version did not spell out that the statistics related to the specific forest.