This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Clayton James "Jim" Kearl plans to arrive at the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., early Monday morning, dressed in his white-trimmed Navy jacket and blue USS Salt Lake City cap.

The 96-year-old Salt Lake City veteran will listen to tales of battle told by two of his fellow veterans, one of whom survived the Pearl Harbor attack at age 16. He will listen to patriotic music, including several tunes played by a country music artist who served as a paratrooper in the Army.

And then, Kearl will rise and lay a wreath at the base of the Freedom Wall — a gesture of remembrance to the more than 400,000 Americans who lost their lives in the deadliest human conflict in history.

He is one of 19 World War II veterans from around the country who were asked to lay wreaths at the annual Memorial Day event.

"I'm very nervous," Kearl said in an interview last week.

Sitting alongside his wife, Betty, at their Sugar House home, Kearl explained he's pretty active for 96. But the wreath he's responsible for is big. It's probably heavy.

Still, deep down, Kearl must know he'll be fine.

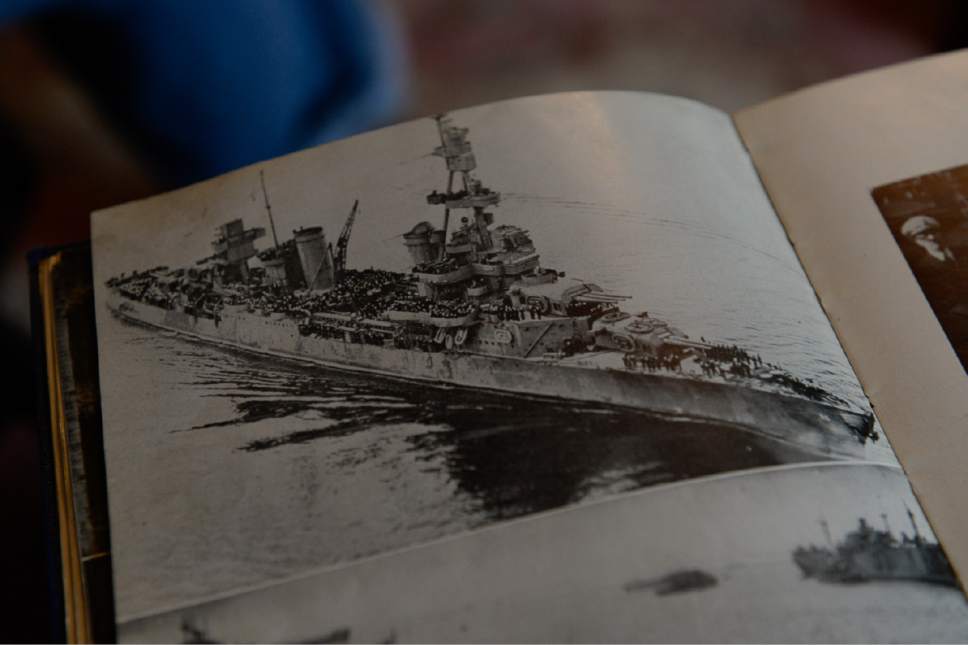

This is a man who witnessed some of the war's largest battles, rising to radarman 1st class aboard the USS Salt Lake City. A man who mastered a revolutionary radar technology to identify Japanese warships and airplanes, and watched the American flag rise on Iwo Jima after weeks of deadly fighting.

He's cool under pressure.

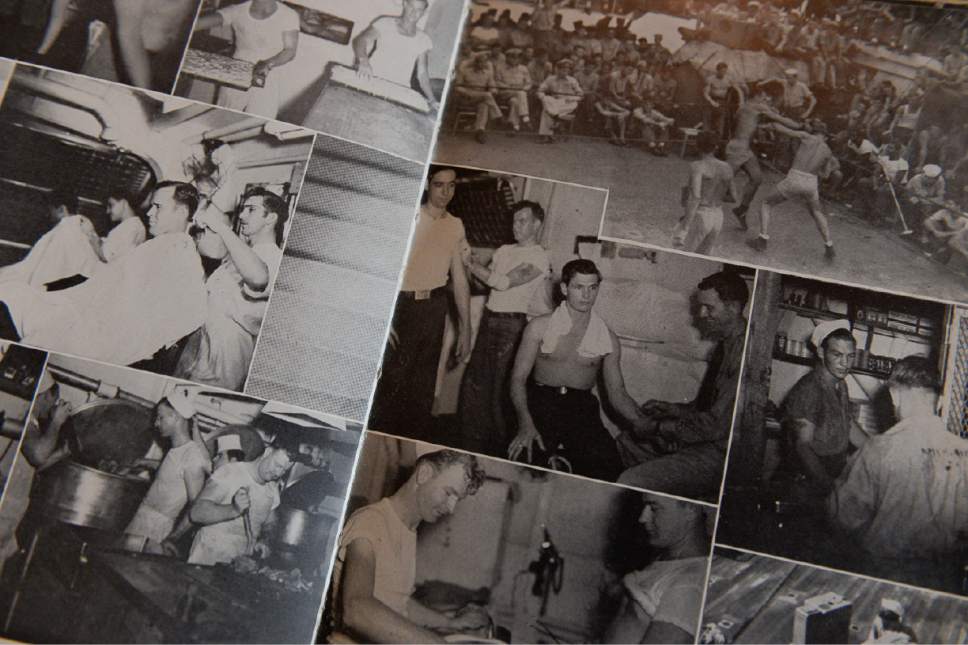

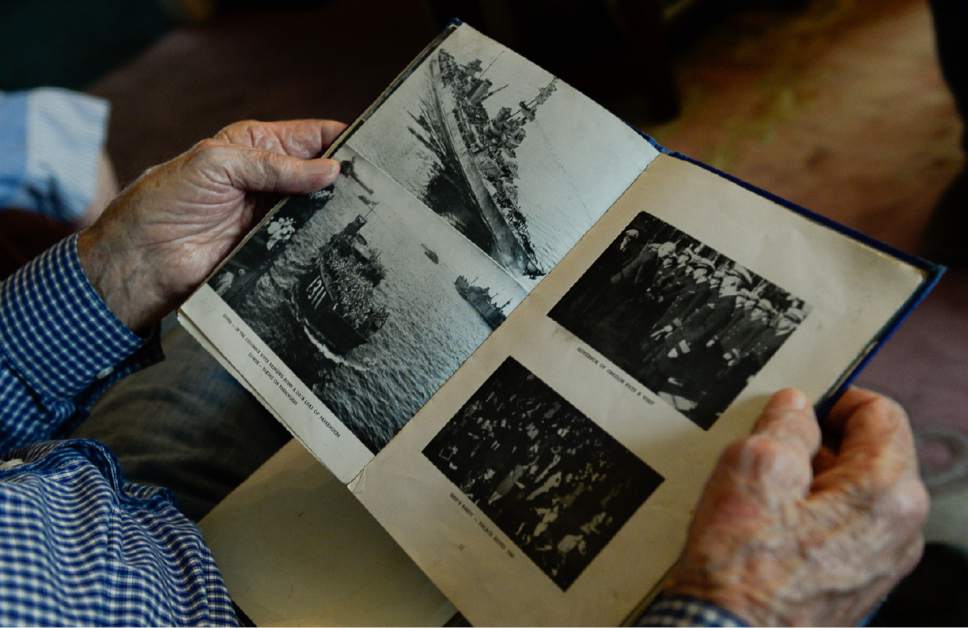

He's also a great storyteller. Flipping through a small weathered book that serves as a historical record for the USS Salt Lake City, Kearl's memories began flooding back.

He recalled watching on his radar as a fleet of Japanese warships closed in on the USS Salt Lake City, not far from the Aleutian Islands, late on the morning of March 27, 1943.

The ship and its crew of 1,200 had endured a four-hour firefight with the Japanese earlier that morning, in what became known as the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. And after several direct hits, the American cruiser was "sitting dead in the water," Kearl said, its fuel tank and engine crippled.

The captain's voice came in over the loudspeakers.

"I hate to say these words," he said, "but prepare to abandon ship."

But in the windowless combat information center where Kearl worked, nobody moved. There was nothing to do but wait and see what happened next: "If we had jumped overboard, we would have froze to death" in the icy waters, he said.

As the Japanese ships drew closer, several American destroyers went for a last-ditch torpedo attack. "We didn't know if it hit anything or not," Kearl said. "But at that point, the ship came alive and started to move, and the Japanese turned and left."

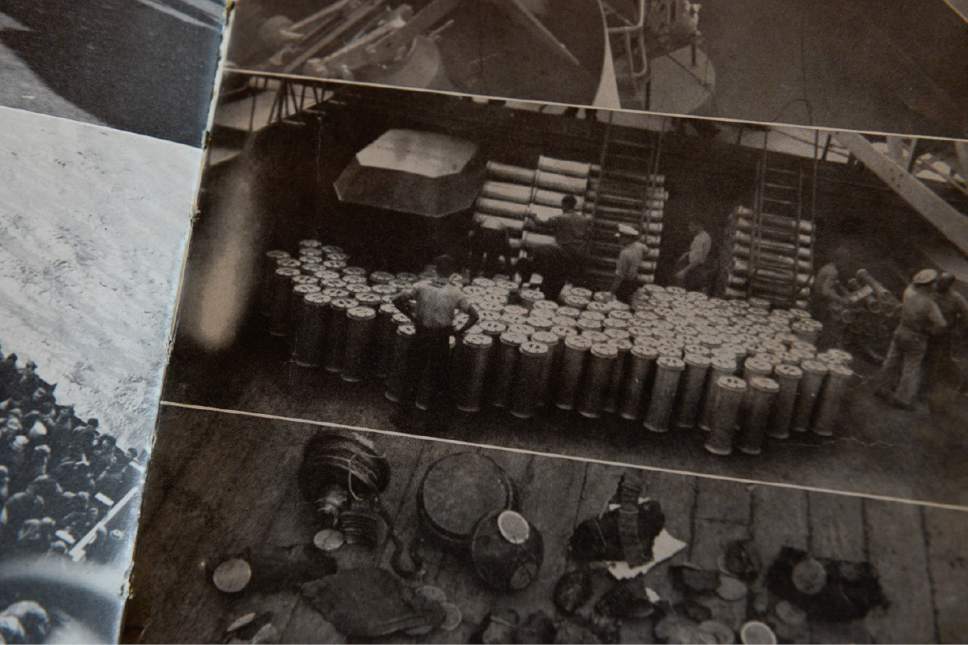

The USS Salt Lake City also participated in the assault on Iwo Jima, bombarding the island regularly for weeks, Kearl said. On D-Day, the ship went around the north side and began firing its 8-inch guns at the island's various caves. The captain "got too anxious," Kearl said, and the ship ran aground just as the Americans gained control of the island.

Kearl and several others went to the aft of the stalled ship, he said, and watched the American flag being raised.

"That was the end of their navy," Kearl said of the Japanese.

Kearl met his soon-to-be wife just before the war. It was love at first sight, he said. They were on their second date — a dinner at a relative's house — when news of Pearl Harbor came over the radio airwaves, Kearl's daughter, Marianne Samuelson, said Wednesday.

Kearl enlisted in the Navy shortly thereafter, at age 21, and served three years. He married Betty, now 92, while home on leave. The couple has seven children. Many of Kearl's kids and other extended family plant to attend Monday's ceremony.

Kearl's cohort of World War II veterans is fast-dwindling. As of 2016, just 620,000 of the 16 million who served in World War II were alive, and some 372 are dying each day, according to Veterans Affairs statistics. In Utah, there are roughly 4,000 World War II veterans still alive.

It was a son-in-law, Doug Brown, who suggested Kearl travel to Washington to lay the wreath, knowing it could be his last chance. Brown, a publisher of American war memorial books, said he was recently talking with the director of the World War II Memorial about a forthcoming project, when the topic of Kearl and the Memorial Day ceremony came up.

"He said, 'Man, we'd love to have him out,' " Brown said of the director. "They are always looking for people [to lay the wreaths], and it is getting harder and harder to find these guys."

Twitter: @lramseth