This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah officials are preparing to face an "unprecedented" assortment of new street drugs that are concocted by mixing already dangerous substances together into one pill or tablet, said Brian Besser, the district agent in charge for the Drug Enforcement Agency.

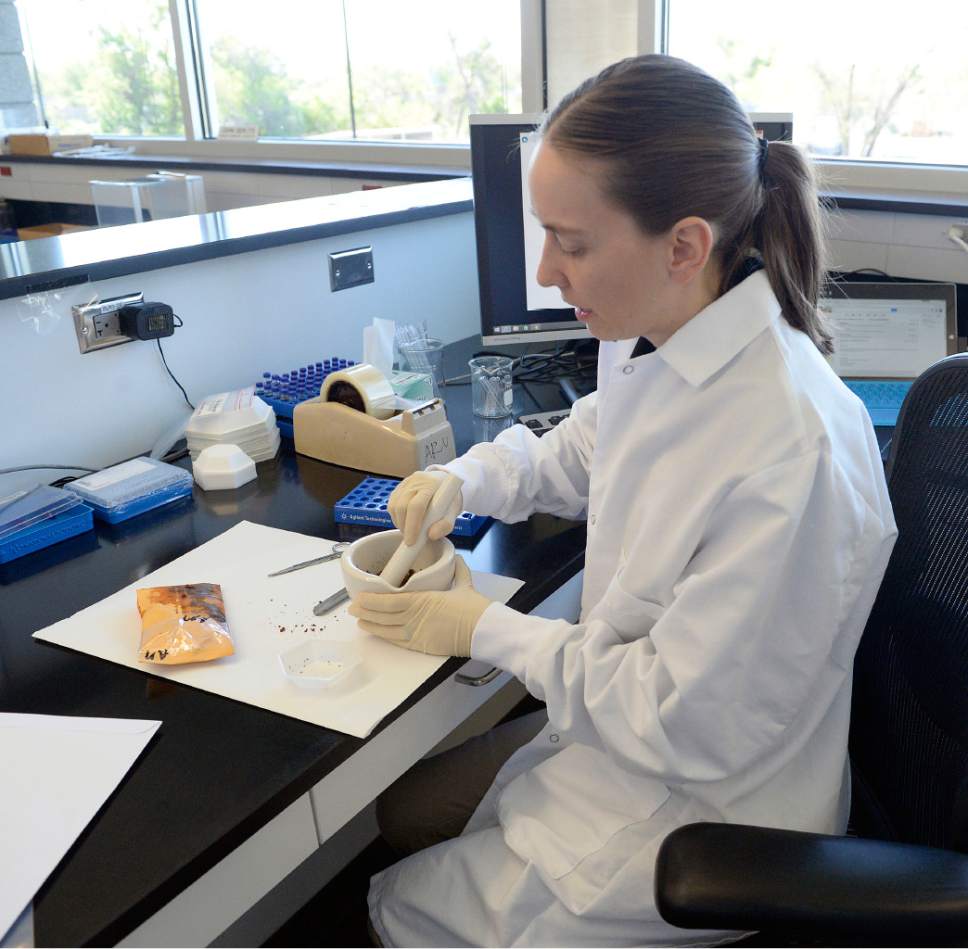

"These are unprecedented times," Besser said Wednesday, speaking to a crowd in front of the new space for the Department of Public Safety's crime lab, which is working to identify the new combinations being sold. "Every day, the flavors change, and every day, the flavors get more deadly."

Since moving into the new building three months ago, analysts have more space and equipment, Utah Crime Lab Director Jay Henry said, and the team has identified the makeup of different drugs quicker, which has become more necessary, given the drug trend.

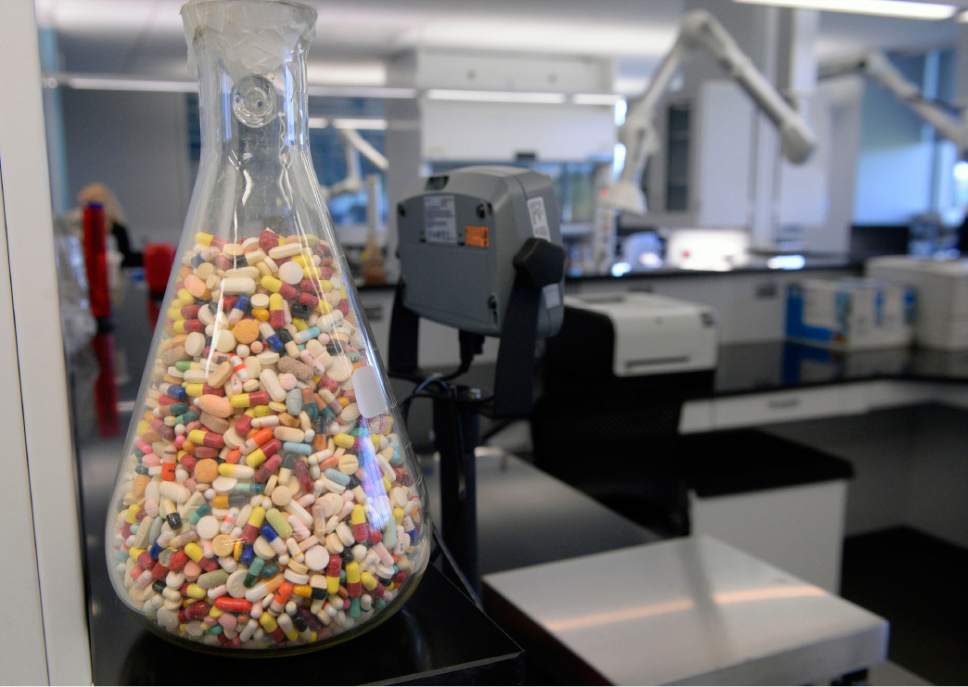

Illicit-drug manufacturers have been creating "designer drugs," some of which contain multiple compounds — such as methamphetamine and fentanyl — in one pill. The pills and tablets not only contain a dangerous combination, Besser said, the amounts of each vary; substances are combined in batches, then pressed into pills, creating an unknown ratio of each ingredient in a single tablet.

"The first 20-25 years of my chemistry career, you might see a new compound every few years, and that was a big deal," Henry said, adding that since 2010, the Utah Crime Lab has identified between 60 and 80 new compounds.

Drugs such as "pink" and other synthetic opioids fit under an overarching trend of designer drugs.

The DEA classified pink as a Schedule 1 Drug after it caused the death of two Park City teenagers last year.

Schedule 1 drugs are substances or chemicals that are defined as having "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse."

Manufacturers also are attempting to bypass controlled substance laws by changing the structure of, or adding a molecule to, a compound to create analog, or similar, drugs, Henry said. Alterations have also been seen with drugs like "gray death," a Schedule 1 opioid that looks like chunks of concrete. A pill similar to gray death was involved in a near-death in Morgan last month.

Recreational-drug manufacturers also modify fentanyl — which can be 100 times more potent than heroin because it is synthetic, said Utah Highway Patrol spokesman Todd Royce. It is even dangerous because some of the pills lack a protective coating, and fentanyl is absorbed through the skin, he said.

When the chemical makeup of a banned drug is changed so it is no longer specifically listed as banned, prosecuting the drugmakers or sellers takes a lot more effort, Henry said.

That is when chemists are brought into courtrooms to argue whether a drug is an analog, Henry said. If the crime lab can show that the drug in question is related to an illegal substance, it can be prosecuted under the analog law, Henry said.

Another trend law enforcement has spotted is chemists searching old pharmaceutical journals to find research about pain medication that was abandoned, in some cases for being too addictive, Henry said.

Crime labs across the country network try to determine which compounds are being created and sold to help officials decide what is necessary to classify as scheduled, according to Henry.

When a compound is identified, the crime lab submits an analysis to the Controlled Substance Advisory Committee, which decides whether to schedule it, pending a vote in the Utah Legislature, said Henry.

And then the sale of that drug tends to drop off, said Henry, creating relatively quick spikes of dealers moving on from one substance to the next. And as drugs are added to the DEA's list of scheduled drugs, Royce said, the parent compound is slightly modified, creating the next drug.

Officers say they hardly see "spice" — a synthetic compound that was added to the list of banned substances in 2011 — anymore, ever since it was added to the DEA's list of scheduled drugs, said Royce.

"We used to see it everywhere," Royce said. " 'Bath salts' was the same thing. As soon as it was scheduled, it dropped off."

Twitter: @tiffany_mf