This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • The Salt Lake Tribune won the second Pulitzer Prize in its nearly 150-year history last week for its investigation of campus sexual assaults. So what about the paper's first Pulitzer? This story looks back at that honor, awarded in 1957 for coverage of a 1956 midair collision that sent two airplanes crashing into the Grand Canyon, killing 128 people in what was then the world's worst commercial aviation disaster.

When a teletype machine alerted The Salt Lake Tribune newsroom that a second airliner was missing somewhere east of Los Angeles on the otherwise quiet Saturday afternoon of June 30, 1956, the paper's staff kicked into gear.

Managing Editor Jim England chartered "one of the fastest small airplanes adaptable for flying in desert areas" and whisked a young reporter, Robert Alkire, and photographer Jack White off to Cedar City, anticipating it was close to wherever those planes might be. Besides, The Tribune had a bureau in Cedar City with the technology to send stories and pictures directly to the newsroom.

Back in the office, reporters like Bob Blair started making phone calls to United and TWA airlines, the Civil Aviation Board, National Weather Service and other potential sources of information about the flight paths of the two planes, which had left L.A. three minutes apart.

"I remember the newsroom being very calm. No one was running around hollering and screaming," recalled Mike Korologos, a longtime Salt Lake City advertising man who was then a sportswriter.

"A lot of the guys in the newsroom were veterans of World War II and the Korean War," he added. "They were tough old codgers and they were good under pressure."

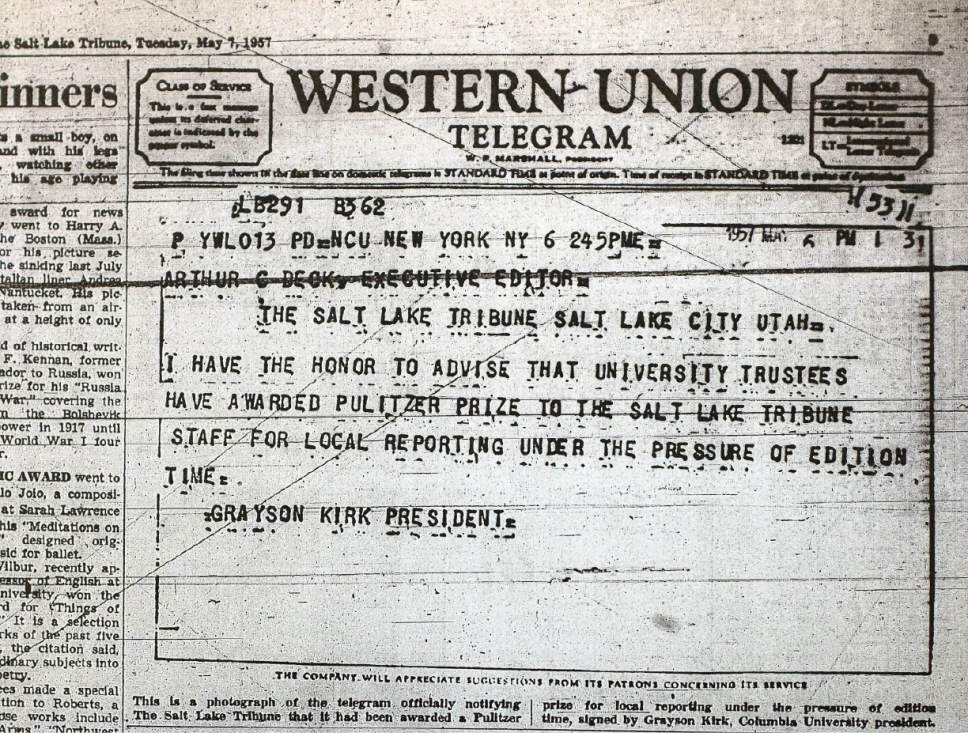

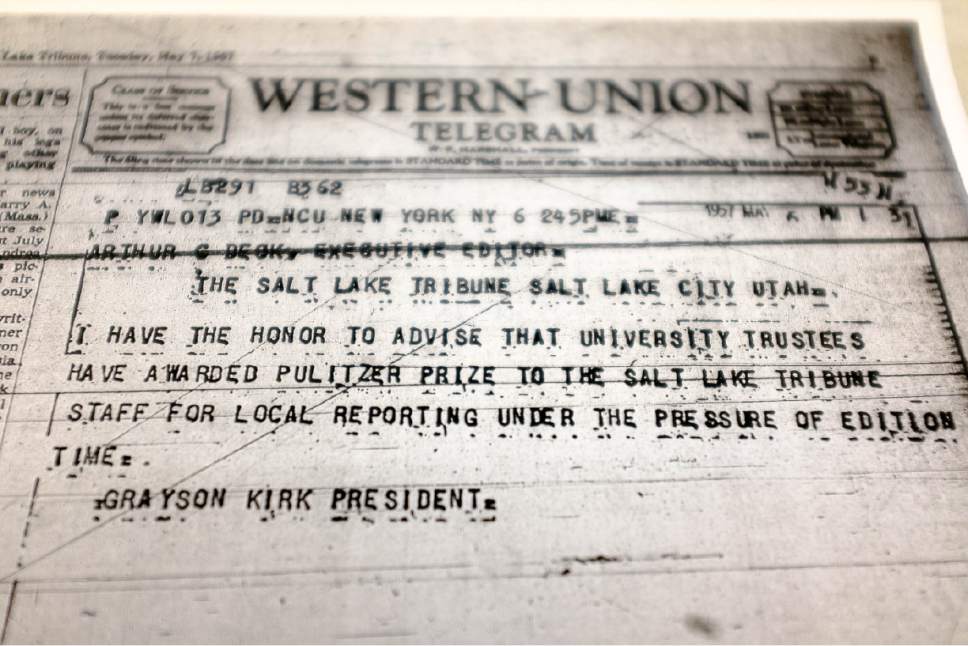

Pulitzer Prize judges thought so, too.

The prize citation they awarded The Tribune in May 1957 heralded the paper's "prompt and efficient coverage of the crash ... in which 128 persons were killed. This was a team job that surmounted great difficulties in distance, time and terrain ... made possible because of the complete coordination of editors, rewrite men, laboratory photographers and technicians."

Blair, now 95 and living in St. George, said England deserves the most credit for "us winning the prize. He realized right away what we needed to do. He was a wild man. He did things without advising [top editor] Art Deck, which he probably shouldn't have done."

England made Blair the rewrite man that first night. Blair pulled together all of the information assembled by various reporters and from the wire services, including grim news that arrived as night fell that plane wreckage had been spotted in the Grand Canyon — and clearly there were no survivors.

The Tribune's Sunday morning coverage included detailed information from the two airlines, including photographs of the pilots and flight attendants, and crash-site graphics by Tribune artists based on the topographic maps of outdoors writer Don Brooks, the self-proclaimed "Dead Fish Editor."

But the key to The Tribune's award-winning coverage occurred Saturday night.

Frank Jensen, who ran the paper's Cedar City bureau, got an interview with the first people to spot the wreckage, Palen Hudgin and brother Henry, operators of a sightseeing operation, Grand Canyon Airlines.

The Tribune team also conferred with a Grand Canyon National Park ranger, who helped them plan a Sunday morning photographic flyover "when haze and shadows in the canyon had been penetrated by the rising sun but the air turbulence wouldn't be too great to permit flying."

So that morning, the speedy plane took off with Alkire, Jensen and Associated Press reporter Frank Wetzel on board. A second, smaller aircraft also departed, carrying photographer White. Both got within 200 feet of the crash sites.

"The reporters aboard gathered materials for their stories. Later, they landed at the Grand Canyon airport for additional pictures and interviews with airline and air search officials," The Tribune reported after getting the Pulitzer. "Within a short time, all were back in Cedar City, where the pictures [and stories] were transmitted directly into [AP's] wire-photo network and used by all the nation's leading newspapers."

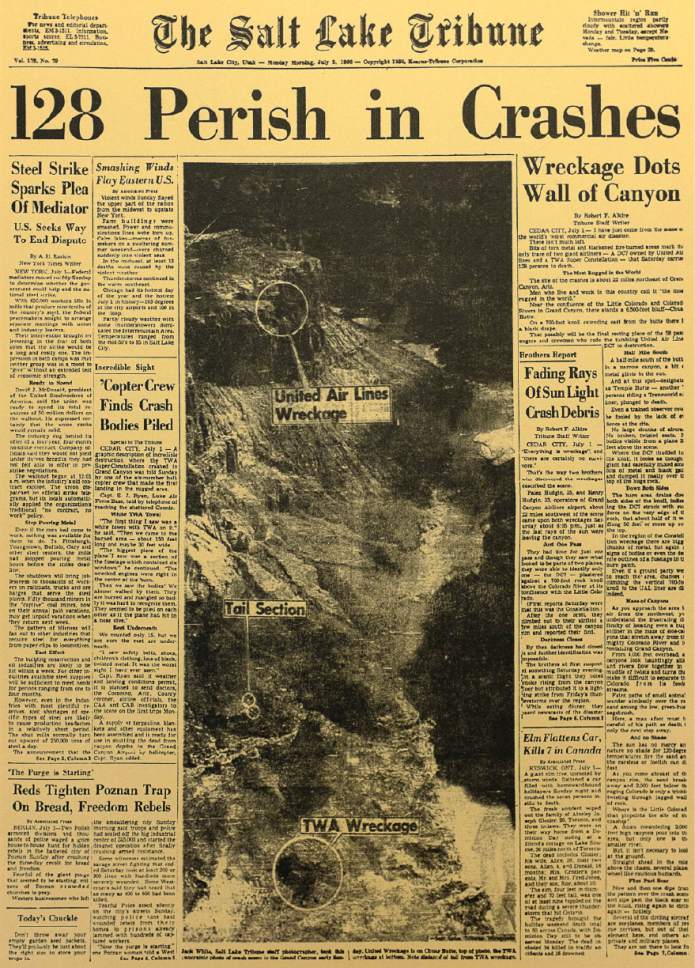

On Monday morning, The Tribune published a crash-site photograph that stretched from the top of the front page to the bottom, a dedication of space unheard of in those days. The main story, under Alkire's byline, also began in unusual fashion — with a first-person lead:

"I have just come from the scene of the world's worst commercial air disaster.

"There isn't much left.

"Bits of torn metal and blackened fire-burned areas mark the only trace of two giant airliners — a DC7 owned by United Airlines and a TWA Super Constellation — that Saturday carried 128 persons to death."

Later, he described the scene:

"Even a trained observer could be fooled by the lack of evidence at the site.

"No large chunks of aircraft. No broken, twisted seats. No bodies visible from a plane 220 feet above the scene.

"Where the DC7 thudded into the knoll, it looks as though a giant had carefully mixed small bits of metal and black paint and dumped it nearly over the top of the huge rock. ... In the region of the Constellation wreckage, there are bigger chunks of metal, but again no signs of bodies or even the definite outlines of a fuselage in the burn patch."

Photographer White also contributed a sidebar story, giving vent to his nightmarish thoughts about what doomed passengers must have felt as the planes hurtled down.

"Sitting in the open door of the plane, safely buckled into a parachute, I thought about the length of time it takes to fall 18,000 feet. Three minutes? Five minutes? Perhaps longer.

"Even one minute would seem like an eternity. What do people do in that time? Are they stunned, unbelieving? Do they panic, scream, try to run? Do they curse the fate they're meeting? Or do they just sit and pray?"

Korologos isn't positive, but "in my heart of hearts I believe" editor England wrote the main article's unconventional opening rather than Alkire, who was 27 and had worked at The Tribune just two years after serving in Korea.

"Alkire was a good workmanlike reporter," Korologos said, "but England had a flair for the un-mundane style of writing prevalent at the time. It was prevalent in his writing of memos, etc. He had a casual style in whatever he did. That lead was a little more dramatic and not characteristic of a 'just the facts' type of reporter that was Bob Alkire," who went on to work for AP before settling into a lengthy career as a spokesman for Kennecott.

Alkire died in 1988.

England stayed at The Tribune only a year after the Pulitzer commendation, ending a 13-year stint to move on to the Idaho Statesman in Boise. He later returned to Salt Lake City to be the head of public relations for EIMCO, a mining machinery company, and died in 2010 at age 93.

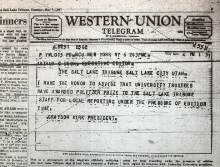

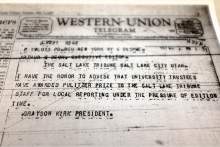

While The Tribune won for "local reporting under the pressure of edition time," two other Pulitzers of note were awarded in 1957.

Playwright Eugene O'Neill became the first posthumous Pulitzer recipient for his autobiographical drama, "Long Day's Journey Into Night." And John F. Kennedy became the first member of Congress to get the award, for his biography "Profiles in Courage." —

The stories that won the 2017 prize

In 2016, The Tribune uncovered troubling practices at BYU in handling sexual assault reports.

Reporters spoke with more than 60 current and former students, who shared stories of how many assault victims felt silenced by BYU's Honor Code or blamed for their assaults by school personnel. Another investigation found that campus officials and law enforcement apparently did not take proper action in responding to multiple sex assault reports against a former Utah State University football player. Widespread reforms — including a sweeping overhaul of how BYU handles sexual assault reports, policy changes at USU and criminal charges against the ex-USU football player — followed The Tribune's reporting.

Here are the 10 stories from that coverage for which judges awarded the paper the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in local reporting:

April 13 • BYU students say victims of sexual assault are targeted by Honor Code

April 15 • Prosecutor says rape case is threatened by Honor Code investigation

April 26 • Sexual assault victims say abusers wield Honor Code as a weapon

May 5 • How outdated Mormon teachings may be aiding and abetting 'rape culture'

May 19 • BYU students who reported sex assaults say they faced presumption of guilt

June 3 • Sex-assault victims and experts agree: Seeing BYU as inherently safe is 'naive'

July 24 • After four women accused a Utah State student of sex assaults, no charges and no apparent discipline

Aug. 16 • BYU Honor Code leaves LGBT victims of sexual assault vulnerable and alone

Oct. 26 • BYU announces Honor Code amnesty for sexual assault victims, other sweeping changes

Nov. 19 • After five new reports, former USU football player charged in additional rapes

Rachel Piper —

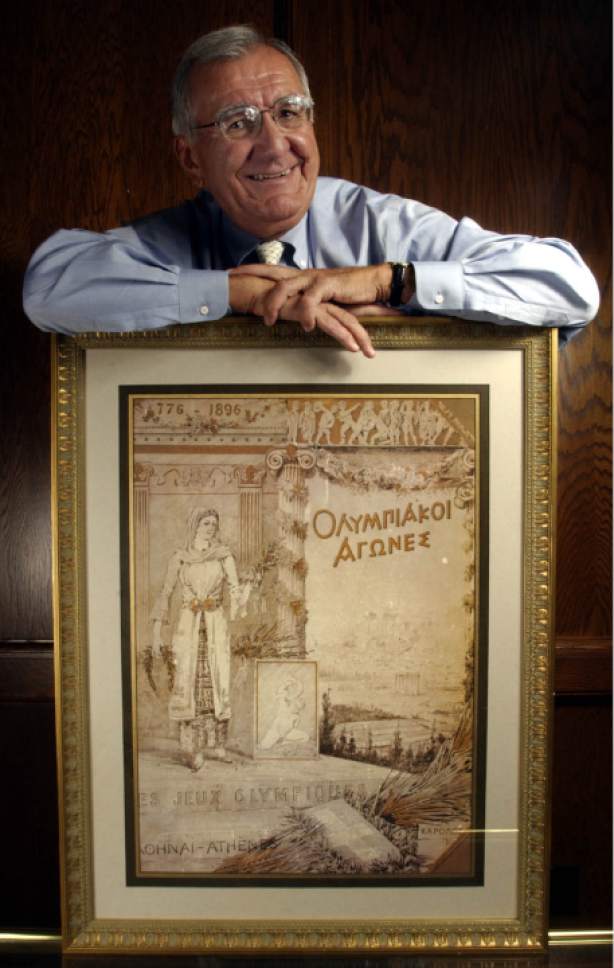

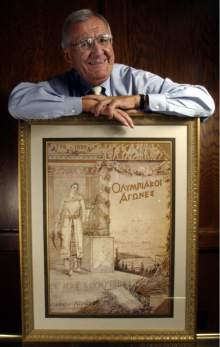

Utah's other Pulitzer

The Deseret News is the only other Utah newspaper to have earned a Pulitzer Prize. In 1962, Robert D. "Bob" Mullins took home the honor for local, edition-time reporting for his "resourceful coverage" of a 1961 murder and kidnapping at Dead Horse Point. An ace investigative journalist, Mullins worked for the News for nearly four decades. He died last year at age 91.