This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • Every Saturday, Salt Lake Tribune columnist Robert Kirby digs into the state's past to enlighten or, at least, entertain Utahns in the present. Have a story to share? Visit Facebook.com/DisturbingHistory, or email rkirby@sltrib.com.

I drove a TRAX train once. No, I did not commandeer it at gunpoint. The opportunity was not only legal, but UTA officials even invited me to do it.

It was a fine spring day in 1999. UTA was set to officially open its first light-rail line in the Salt Lake Valley. Many important dignitaries were invited to take a ride and see for themselves that there was nothing to fear.

I wrote a breaking news report extolling the virtues and the deficiencies in the new transportation system. The main issue I raised is that TRAX trains — and later FrontRunner — lacked cowcatchers, a plow device mounted on the front as a means of flinging obstacles out of the way.

Cows were the main culprits in the early days. They still are. As a cop, I investigated and diagrammed a number of cow-train accidents. There was even a rough mathematical formula for it: C+RR+T/50=1/2.

Here's how it works: If a cow is standing on railroad tracks and sees a train a mile away approaching at 50 mph, it will be only halfway through wondering what the hell is going on by the time the train arrives and solves the problem.

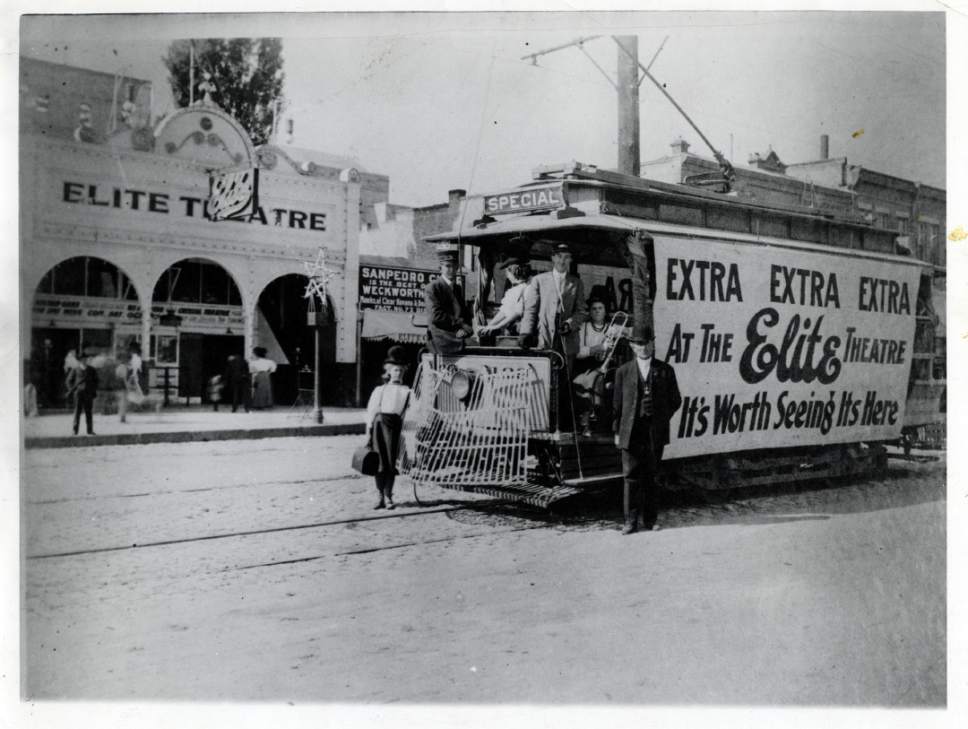

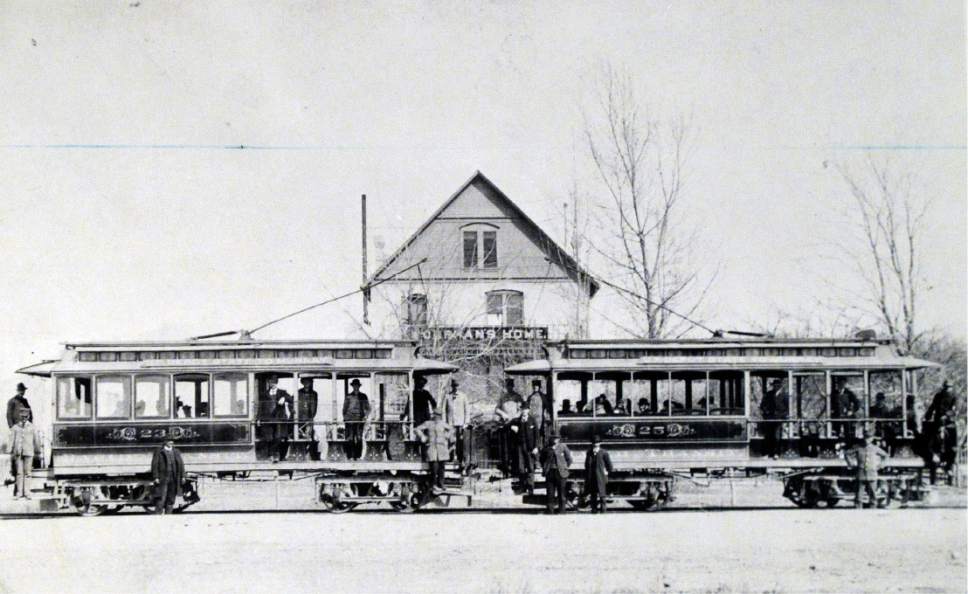

People aren't much better. Public transportation by rail along the Wasatch Front has always been necessary and problematic. The streetcar system in early Salt Lake City was a marvel yet dangerous.

Early electrical streetcars had both an operator (the person driving) and a conductor (the one who collected fares and threw off misbehaving passengers).

Today's TRAX and FrontRunner riders must contend with lots of things, but frequent robberies aren't one of them. Armed banditry and shootouts were hardly unheard of.

On Jan. 7, 1904, Salt Lake City streetcar operator Amasa L. Gleason and conductor Thomas B. Brighton were murdered during a robbery near 1300 East and 200 South. The suspects were captured almost immediately.

The next day, a mob of streetcar operators and employees stormed the police department seeking the killers. They left only upon discovering that there was no one to lynch. The suspects had been moved to a penitentiary for safekeeping.

Mostly, passengers had more to fear from themselves than violence. In the early days of downtown commuter rail, riders disembarked straight onto the street. It's surprising how often they were then hit by passing traffic or collided with utility poles.

If passengers weren't getting hurt riding streetcars, other people were. On Jan. 22, 1910, Elinore Berryman, 25, threw her 6-month-old child to safety just before she was struck and killed by a westbound South Temple streetcar near the southwest corner of 400 East and Brigham Street.

On July 12, 1920, while responding to a blaze, a Salt Lake City fire engine collided with a streetcar at 200 South and 300 West. Five firefighters were injured. Lt. Asa Hancock died the following morning, the first Utah firefighter killed in the line of duty.

On Sept. 20, 1920, in Ogden, Richard Saunders, 45, was killed when his motorcycle stalled on streetcar tracks on Washington Street near 13th Street. The streetcar had to be jacked up to remove his body.

The mayhem continued until 1946, when the last Salt Lake City streetcar made its final run. The rails were eventually ripped up or paved over. The age of the automobile had claimed the life of the streetcar.

Five decades later, thanks to rising fuel costs, death rates and gridlock, commuter rail returned as both a cheaper, more timely and safer way to commute.

As before, only time will tell if that holds true.