This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Since the launch of the Our Schools Now ballot initiative in November, organizers have emphasized that an individual school's slice of $750 million would hinge on improved performance.

But beyond raising Utah's income tax from 5 percent to 5.875 percent, the initiative has been short on specifics for how schools would spend the infusion of cash.

On Thursday, Our Schools Now shared the draft elements of its performance plan, which would see all schools receive additional funding on a per-student basis for the first two years after the tax hike. After that, schools would need to increase proficiency rates, graduation rates and college-readiness rates by 1 percent each year to receive a full share of per-student funds.

"They can't be expected to make this miraculous change the first year out," Our Schools Now committee member Bob Marquardt said. "By the third year, we should start seeing some difference from this."

Marquardt said the initiative is still gathering information and that nothing is set in stone. But the effort, if successful, would create a new funding account to be dispersed when schools satisfy performance requirements.

In its current form, new funding for elementary and middle schools would be based on math and English test scores, while high schools would be measured against graduation rates and college-readiness rates. Schools would also have the ability to select their own performance metric, for up to 20 percent of their Our Schools Now funding, subject to school district approval.

High-achieving schools would be excluded from the annual improvement requirements once they reached certain thresholds, for example a graduation rate higher than 93 percent or when more than 75 percent of students are proficient in math and English.

"We're talking the top tier of performers," Marquardt said. "You're not going to punish them for dropping back a little bit."

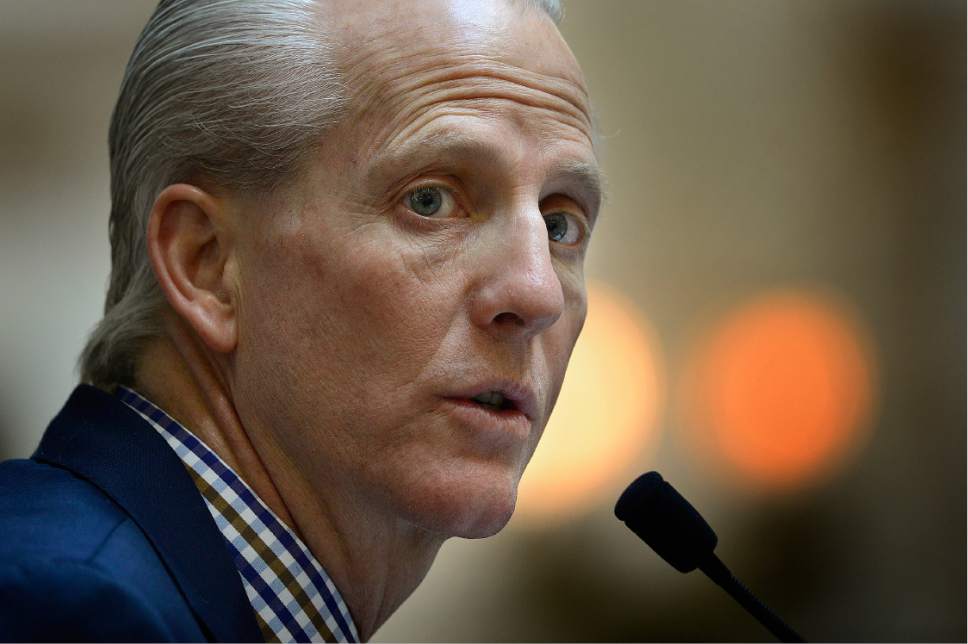

Lawmakers have resisted the initiative's push to raise taxes, and Senate President Wayne Niederhauser, R-Sandy, reiterated Thursday that he views the income tax as a "tax on productivity."

"That is the wrong place to do it," he said.

Niederhauser and other Senate Republicans are working on a series of tax-reform bills aimed at stabilizing state revenue. Those adjustments would be initially revenue neutral, Niederhauser said, but would allow for budget growth over time.

He said Our Schools Now highlights the need to strengthen the state's revenue streams. But he prefers an incremental approach, like the gas and property tax increases approved in 2015.

"If every Legislature would do that much, or something that would help the system going forward," Niederhauser said, "no one legislature has to enact a huge tax increase."

Marquardt said there was some speculation before the legislative session that lawmakers might approve an increase in public education funding, negating the need for Our Schools Now.

But with two weeks to go, and with the new focus on sales tax reform, Marquardt said it is increasingly unlikely schools will receive a major investment this year.

"At this point it's very clear that this initiative is going forward," he said.

A recent Salt Lake Tribune-Hinckley Institute of Politics poll found a small majority of Utahns support the tax increase initiative.

Nolan Karras, a former Utah House speaker and executive committee member for Our Schools Now, said that if the effort to fund schools fails to reach the ballot in 2018, or is voted down by Utahns, it won't be the end of a business-led effort to support schools.

That might mean additional initiatives in subsequent years, Karras said, or a sustained lobbying effort in support of public education.

"We're developing a pro-education group that is pretty deep and wide and that group is not going to go away," Karras said. "It will be a factor whatever election we're in."

Marquardt said there are still details to work out, including what happens to leftover funding when schools fall short of annual performance increases.

That money could be given to school districts, he said, or returned to the state for the education system as a whole.

"The way this is written, it would go back to the state," Marquardt said. "That's one of the issues we're still listening to comments on."

He said initiative organizers are also watching bills under consideration by lawmakers.

It is beneficial for the wording of a ballot initiative to be as short and simple as possible, he said, and school-accountability programs created or adjusted by the Legislature could replace the Our Schools Now plan.

"Depending on what comes out of this Legislature, we could point to a bill that has passed and that takes care of it," he said.

Our Schools Now is focused, he added, on the need to support teachers, including recruitment, retention and training.

It is good that lawmakers are reviewing the state's tax structure, Marquardt said, but adjustments that don't generate additional revenue aren't sufficient to meet Utah's needs.

"Our emphasis and our direction is to increase funding for education," Marquardt said.

Lisa Nentl-Bloom, executive director of the Utah Education Association, said the union appreciates the work of Our Schools Now to put forward a solution to Utah school funding, which is, and has been for years, the lowest in the nation on a per-student basis.

"We are especially gratified that they recognize that having an effective teacher in every classroom is the strongest factor to our students' success," she said. "UEA has been very glad to join Our Schools Now in this initiative."

Twitter: @bjaminwood