This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

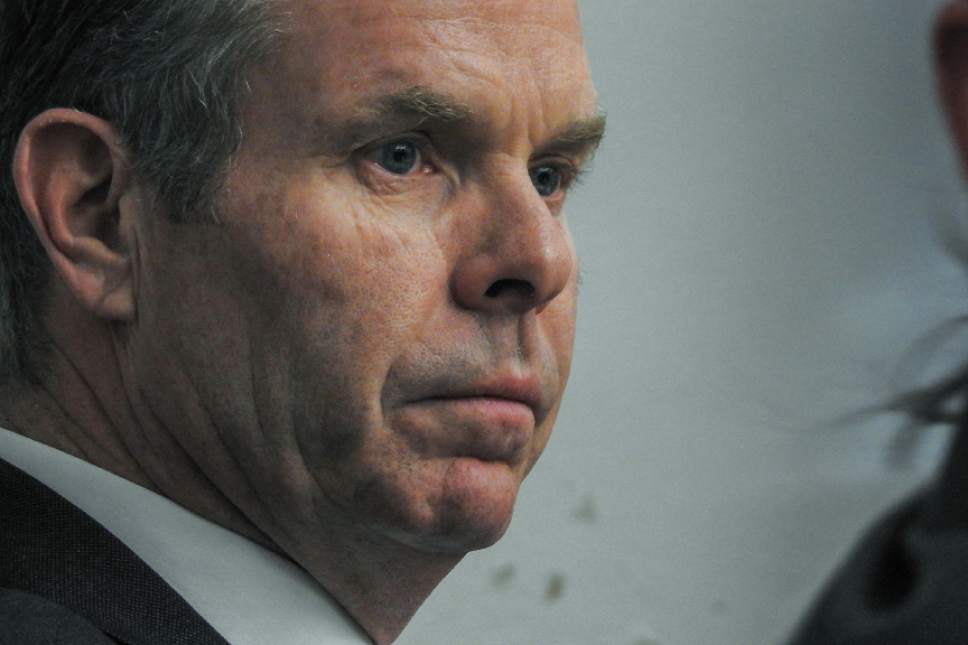

More than 2½ years after he was charged, former Utah Attorney General John Swallow opened his defense Wednesday before a jury with a blistering attack on prosecutors and investigators, his lawyer portraying the ex-officeholder as the victim of a "political frenzy."

"This case does not involve investigation; this case involves 'inventigation,' " in which investigators twisted facts and witness statements to reach the outcome they wanted, defense attorney Scott C. Williams said as the state court trial opened on Swallow's 12 felony counts and one misdemeanor charge.

"Listen to the witnesses," Williams told the jury. "From what we've heard, they are not going to cooperate with the state's narrative."

Williams gave his opening statement before a jury of seven men and five women in a trial that is scheduled to last 16 days. Williams for the first time outlined Swallow's defense, focusing on politics instead of criminal acts as the reason the former attorney general is before the court.

"This case starts with politics and, I think you'll see, continues with politics," Williams said, pointing to the five investigations that erupted in 2013 over allegations of a pay-to-play scheme inside the Utah attorney general's office.

"This political attack, this frenzy, went on for about a year," the attorney said. "And it worked."

Swallow, a Republican, resigned after 11 months in office amid a political scandal that became the biggest in Utah history.

The upheaval also engulfed Swallow's immediate predecessor, Mark Shurtleff, whose own criminal case was dismissed last year but whose visage cast a long shadow over the proceedings.

Salt Lake County Deputy District Attorney Chou Chou Collins cast Shurtleff as the ringleader of a trio who set out to amass power, privilege and money by using the office of the Utah attorney general. She outlined a case that includes gifts of gold coins, and luxury trips on a Lake Powell houseboat and to a ritzy California resort.

In her opening remarks, Collins showed the jury a huge poster with a triangle comprising life-size photos. At the apex was Shurtleff, and below was Swallow on the right with Timothy Lawson, Shurtleff's friend and "fixer," on the left.

"You've got this power-greed-corruption triangle here," Collins told the jury. "That's the basis for this story."

From there, Collins portrayed a complicated web of storylines and relationships, failed business deals, allegations of strong-arm tactics, extortion and a cover-up.

"I know it sounds like a lot," Collins said, "but every count has specific facts."

Swallow has pleaded not guilty to charges that include racketeering, bribery, obstruction of justice, accepting gifts, evidence destruction or tampering and misuse of public funds.

Williams countered, saying much of the state's case was built on the words of criminals, pointing to the state's opening witness, businessman Marc Sessions Jenson, who has served prison time because of a securities-fraud conviction.

Swallow's attorney called Jenson a career criminal and a "con man," who tried to buy his way out of prison and has changed his story over time.

Williams attacked Jenson's expected testimony involving meetings at the posh Pelican Hill resort in Southern California and what the attorney characterized as a "big $35 million conspiracy" that allegedly involves Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes, R-Draper, and former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev.

"This is a brand-new story, and it's a good thing for you as jurors that it's coming out," he said, "because it is just completely false and misproven. It will be misproven."

Jenson may be the prosecution's most important witness if it hopes to prove the racketeering charge.

On the stand Wednesday, Jenson repeated a story that has become familiar since he went public in 2013 with allegations of a "shakedown" for money at the same time he was facing criminal charges brought by the attorney general's office, when Shurtleff was at the helm.

That account includes paying Lawson, who died last year, for access to Shurtleff and footing the bill for the Pelican Hill junkets Shurtleff and Swallow took.

Jenson testified that Lawson showed up one day in 2007 at his office while charges were pending and presented himself as Shurtleff's right-hand man, who could facilitate a resolution to Jenson's legal woes.

Jenson said he didn't believe Lawson, so Lawson called Shurtleff and put him on the phone with Jenson.

"He said, 'Lawson is your conduit to me,' " Jenson told the jury. "He said, 'You got to pay him.' "

Jenson testified that he paid Lawson amounts ranging from $2,000 to $10,000 between 2007 and 2010.

Later that year, Swallow, then a private attorney and a fundraiser for Shurtleff's campaign, also showed up, Jenson testified. Swallow said he was the "heir apparent" to Shurtleff and would be going to work for him as a civil division chief but needed to do some legal work because, according to Jenson, "I [Swallow] can't live on what I can make in the attorney general's office."

In 2008, Jenson got an unusual plea deal in which his efforts to pay restitution were controlled by the attorney general's office.

In January 2009, after his plea deal, Jenson moved into the posh seaside resort called Pelican Hill, where he was paying about $1,000 a night to stay in a villa.

"Did anyone come to visit?" Collins asked.

Jenson grinned and laughed.

In May, Shurtleff, Swallow and Lawson flew down, stayed in a separate villa, played golf and ate meals, all on Jenson's dime, the businessman said.

Prosecutors introduced photos showing Shurtleff and Swallow at the resort, eating poolside meals and playing golf. They displayed receipts that included room-service charges of $84 for a 12-pack of diet Coke and $8 for M&Ms.

Golf charges by Shurtleff, Swallow and Lawson topped $1,200, and a receipt showed a stone massage for $220, signed for by Swallow.

In all, that May visit cost as much as $7,000, Jenson testified.

Late Wednesday, prosecutors started asking Jenson about a second trip to Pelican Hill in June that Jenson said cost him between $12,000 and $15,000.

Collins asked Jenson why he continued to pay Lawson and foot the bill for Shurtleff's and Swallow's trip.

Jenson did so, he said, because the attorney general's office was monitoring his payments toward the $4.1 million in restitution he owed from his 2005 criminal case and could send him to prison if he didn't obey.

Prosecutors are expected to continue questioning Jenson on Thursday about the second Pelican Hill trip.

At a hearing two weeks ago, Jenson testified that the outing included a secret meeting involving officials from the Utah Transit Authority, Hughes and Reid. Hughes has adamantly denied he was at the resort and may be called as a defense witness.