This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Narrowly missed by workmen's boots and the shuffle of folding chairs, a ball of fuchsia-colored yarn unfurled on the carpet. Ellie Brownstein's callused hands pulled on the loose thread, gently guiding it over a pair of knitting needles that softly clicked as she formed the first few rows of a hat.

As a projector displayed a new PowerPoint slide, Brownstein's fingers continued in the easy and familiar rhythm while she craned her neck to see above the rows of folks bundled in winter coats. "Proposed Principle No. 1," the screen read, "Donald Trump's agenda will take America backwards, and it must be stopped."

Brownstein signaled her support for the message by voicing a "Yea" that faded into the unanimous agreement expressed by the more than 120 people gathered for the first meeting of Salt Lake Indivisible, a group formed in the wake of Trump's election. She then continued to work on the pink pu—- hat that would soon look like the pointy-eared one she and many others wore last month at the Women's March on Washington to protest the newly elected president.

"I'm still knitting hats," said Brownstein, a 54-year-old Salt Lake City resident. It's her way of explaining why she's at the organizing meeting on a cold Wednesday night in February: Though it has been weeks since Trump's inauguration, the dissent over his presidency persists. It didn't end with the march, she says.

It's a growing resistance.

Grass-roots anti-Trump movements have emerged nationwide since the election in a new wave of progressive activism that threatens to dog the administration for the next four years. In Utah, a Republican stronghold, that includes several so-called "resistance groups" determined to challenge what they believe is an assault on democracy with protests, phone calls and town hall sit-ins.

The coming months will determine whether they persist or unravel. But for now, they're dedicated, they're feisty and they're mobilizing.

—

How did it start?

As Joanna Smith drove home in her minivan, her mind was still replaying the meeting she'd just left. How would this work? What would they accomplish? Would anyone join? Was she the right person to lead this?

Smith's boyfriend listened as she talked, mostly to herself, about women and resistance and marches and organizing and Trump. He interjected only when they pulled into the driveway.

"You've used the word 'unite' like five times in the five-minute drive," he said. And that's when Smith stumbled onto the answer to the question she knew had to be addressed first: What would they call themselves?

"Utah Women Unite," Smith whispered as she slid out of the car.

The group — with roughly 8,000 members on Facebook and 200 more added each day — is now one of the largest of at least 10 resistance movements forming in Utah. Smith, a 34-year-old single mom, started the group to register Utah as a "sister state" for the D.C. women's march Jan. 21. She also planned another march on the Utah Capitol for two days later — as the legislative session kicked off. With a flood of followers, she realized it wouldn't just be about the protest.

"This needs to be something more than a march," she recalled thinking. "There has to be more to it than that."

Utah Women Unite has since evolved into a structured activist organization with 30 committees and eight directors targeting different facets of women's rights, including education, queer identities, people with disabilities and safety and security. The group looks to encourage women to run for office, to lobby legislators about rape-kit testing and equal-pay bills and to push back against policies instituted by the Trump administration.

"We're literally one executive order away from losing things that our mothers and grandmothers in previous generations have fought for," Smith said.

Most of the other resistance groups have formed in much the same way: a couple of clicks on the computer screen fueled by Trump's election. For Utah Indivisible, it took two sisters, mounting frustration and a Google Docs spreadsheet.

Courtney Marden and her sister, Kellie Henderson, formed the state's chapter of the nationwide Indivisible movement, a resistance guide started by current and former congressional staffers, on Dec. 19. They downloaded the instructions and started a Facebook page that has since grown to 5,000 members.

"It's another full-time job," said Marden, a 37-year-old nurse, as her 19-month-old daughter cried in the background. "We can't be passive."

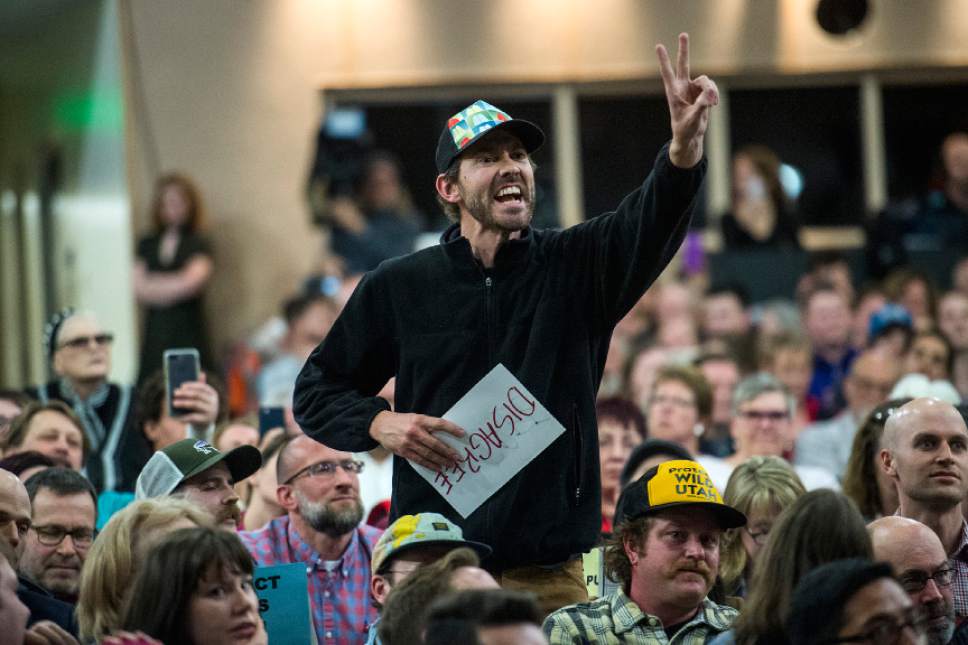

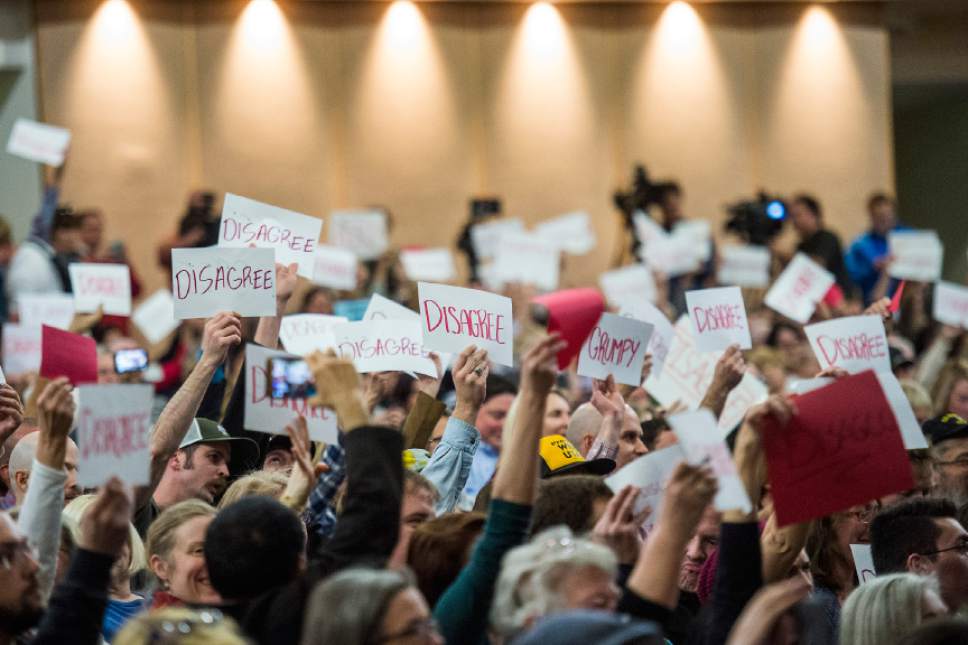

Utah Indivisible focused early on Rep. Jason Chaffetz's town hall this month. The group urged members to attend and question the congressman. One leader created and shared a document that advised: "Ask pointed, leading questions that force Chaffetz to commit to a position or action. We want him to tie himself into knots while the eyes of the nation are on him."

The town hall devolved into a raucous release of pent-up energy. The crowd shouted over Chaffetz's answers and exhorted him to "do your job" and "explain yourself." They booed when he mentioned Trump and they often cut him off midsentence.

The Republican Party later attacked Utah Indivisible for bringing "violence and intimidation" to the meeting. And Chaffetz questioned, and later walked back, whether the audience members were paid protesters from out of state.

Marden says those comments brought attention — and added pressure — to the group that she wasn't expecting.

"Everyone's looking to see how we're going to grow," she said, "and how we're going to hold onto this national spotlight."

—

So what's next?

On Monday, they called about Trump's pick for labor secretary. On Tuesday, they called about Trump not releasing his tax returns. On Wednesday, they called about the Affordable Care Act.

These are just a few of the "phone blitz" campaigns led by members of Utahns Speak Out last week. Each day, the progressive group inundates congressional offices with targeted concerns about the new administration. Sometimes they reach a staffer, but often they're getting full voicemail boxes. Their goal is to be the organized opposition.

Jason Perry, director of the University of Utah's Hinckley Institute of Politics, says that's not enough.

"For these groups that are calling themselves 'the resistance' to be successful," he said, "it will have to become something more than just a reaction to President Trump."

So far, the Republican president — who won Utah with 45 percent of the vote — has been the aim, but several of the resistance groups plan for more. A few have held initial organizing meetings for their members to plot out the next steps, and there have been a slew of protests and marches in Salt Lake City just about every weekend since Trump's election.

For Utahns Speak Out leader Madalena McNeil, it starts with talking to Utah's representatives and senators in person. She's made petitions for each congressional member to hold a town hall meeting in the state. The one for Sen. Orrin Hatch got the most response with 2,128 signatures. The least? Rep. Rob Bishop with 342.

Regardless, none of the leaders pledged to speak with constituents face to face. McNeil booked a venue anyway. The group, she said, plans to hold a "town hall for all" so constituents can air grievances — with or without a member of Congress present.

"We're going to let people ask questions, even if they're asking them to an empty chair or an empty podium," McNeil said, joking that maybe she'll order cardboard cutouts of the representatives to put on stage.

While that's a start, Perry said, the resistance movement might better be able to capitalize on the momentum by fostering its own candidates.

"The great secret to protests or movements is that you find a way to turn that energy into some kind of action," he said. "That often requires you to focus on very key issues that are important to your group and you turn those issues into candidates."

It's a tactic the tea party used, gaining seats in Congress during the 2010 midterm, including the election of Utah Sen. Mike Lee, and beyond. Though today's resistance is not an exact parallel, the Indivisible movement, in particular, mimics how the tea party disrupted the status quo by channeling frustration into a concerted effort.

Salt Lake Indivisible, one of 4,500 Indivisible groups nationwide, chose to focus on four areas: Obamacare, immigration, the Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments. Group co-founder Joanne Slotnik says the next step is figuring out how to have an impact on those objectives.

At the first organizing meeting in February, members circled around posters, each with the name of a Utah congressional leader written at the top in black marker. They brainstormed and bandied ideas. Are phone calls to Hatch really working? Should Democrats in the state register as Republicans so they can vote in the primary? How will they take this movement to the ballot box?

Slotnik, a 69-year-old retired attorney with gray hair dropping to her shoulders, is pretty cavalier in saying she has no idea what she's doing in leading a resistance.

"We started this thing, but we're figuring it out as we go along," she said. "This is grass roots. I'm not a professional organizer."

While Slotnik suggests that may be a shortcoming, she also sees it as "the only silver lining I can find in the whole situation" — that people who have never met before are coming together to respond to the Trump presidency.

—

Can it last?

When Martha Black mounted the last stone step leading up to the Capitol, her heavy breath pouring out as white steam in the cold air, she turned around and looked back. Behind her was a crowd of thousands of Utah women treading through the snow and slush, speckled with pink hats and posters.

"I couldn't believe the amount of people that showed up that day," she said.

Black, now a member of Utah Women Unite, says the march on the Capitol in January cemented her passion for the resistance. She acknowledges, though, that for the movement to last, there's a grocery list of repairs needed. That starts with diversity.

An immigrant from Mexico, Black says it's crucial to include people of color. She's been promoting events and translating posts into Spanish but insists that's not enough. Trump labeling minorities "rapists, criminals and drug dealers," Black believes, has alienated and silenced the populations that need to speak out the most.

And without addressing some of the weaknesses, Perry suggests, the movements will have a "certain life span." One of the major setbacks he sees is a "lack of some kind of consistency of message." With at least 10 resistance groups in Utah and thousands nationwide, it's unclear how, or if, a consensus might be forged. They have to actually be indivisible, Perry notes, in action and not just in name.

"If there are many different groups, all with different priorities or different demands," he said, "the message can become confused."

Growing pains are to be expected, Utah Women Unite leader Joanna Smith adds, in a weeks-old grass-roots resistance. They'll work through them, she promises, and continue onward — even if that means a march every day for the next four years.

It's a plan Ellie Brownstein wouldn't oppose. The Women's March on Washington was "the first time I'd felt hopeful since the election," she said. As she talks, two kids in the back of the room flip through the pages of a picture book called "The Trouble With Chores" and Brownstein folds the half-finished hat she was knitting into her purse.

The work, she said, will continue another day.

ctanner@sltrib.com Twitter: @CourtneyLTanner