This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Mentally ill inmates charged with crimes, but who have not been tried, languish in jail cells for months because Utah does not provide enough hospital beds and specialists to treat them.

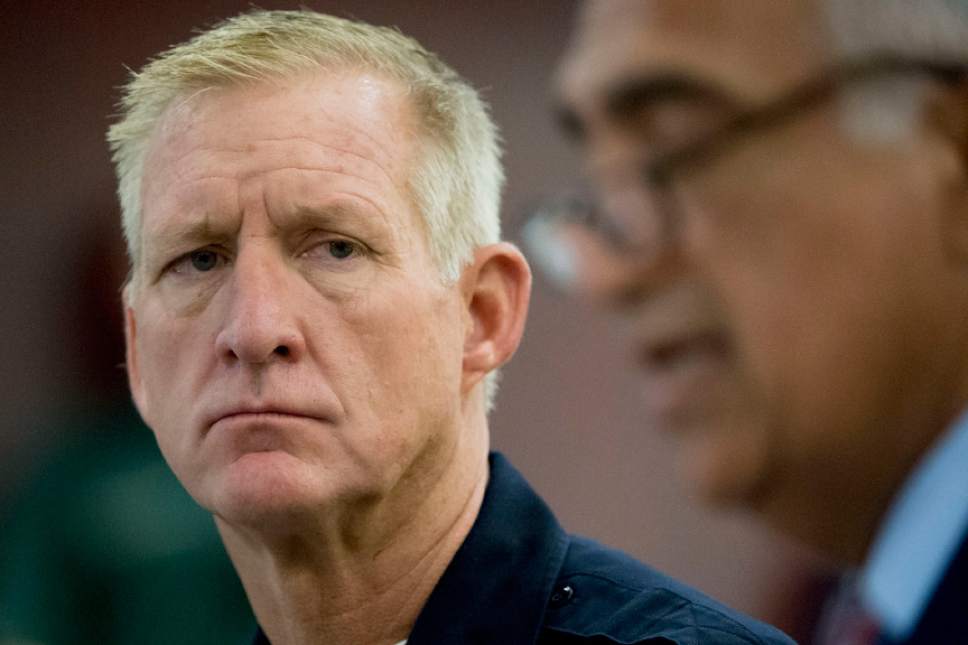

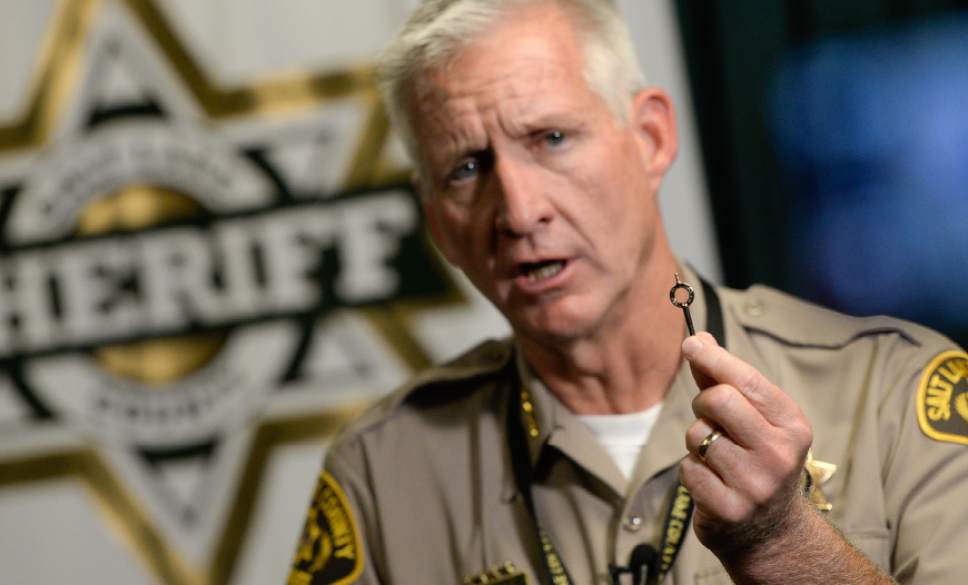

Salt Lake County Sheriff Jim Winder called the situation "abhorrent."

"The fact that an individual can be maintained in a correctional facility in our country without a [case] disposition is the epitome of a problem," Winder said. "I can't even find the right words for it."

These inmates allegedly broke laws and have been deemed incompetent to stand trial. Usually, they are ordered into treatment after competency hearings in an effort to make them fully aware of their circumstances and rights.

The charges against them run the gamut from petty misdemeanors to violent felonies. In some instances, they wait in jail for treatment longer than a standard sentence for their alleged crime, according to the Utah Disability Law Center, which filed suit in U.S. District Court for Utah against the state in 2015, claiming violations of constitutional rights.

"At any given time, there are 40 to 50 people on this wait list," said Aaron Kinikini, of the Disability Law Center. "County jails are set up to house inmates ... not to provide crisis management."

One problem among many is that the state has 100 beds for such individuals, so overflow inmates are placed in county jails, where they wait for months for a bed at the Utah State Hospital.

In its lawsuit, the Disability Law Center highlighted a 71-year-old plaintiff identified only as S.W. He was booked into Salt Lake County Jail March 21, 2014, on a shoplifting charge. More than 13 months later, he was found mentally incompetent to stand trial and was committed to the state hospital for treatment to bring him to a legally acceptable competence.

But four months after the court's order — and after nearly a year and a half in jail — S.W. had not been admitted to the hospital.

The waiting list to get into the state hospital for treatment had doubled every year for three years prior to 2015 from an average of 30 days to 180 days, according to the lawsuit.

Further, it alleged that inmates were sometimes kept for months in solitary confinement for minor crimes.

Since May, the Utah Attorney General's Office and the Disability Law Center have been negotiating toward a settlement. Neither side is willing to discuss specifics at this point. No solution appears likely without help from the state Legislature, which convenes on Jan. 23.

The hang-up to a resolution apparently is that lawmakers would have to allocate a substantial sum for more facilities and practitioners to ensure that inmates are not sitting in jail for months without treatment and without trial.

"It all comes down to the mighty buck," said Winder, adding that the treatment of the mentally ill should be prioritized over almost everything.

But the fall-back position is jail, the sheriff said.

Not only is that backward, he said, it's not the most financially prudent strategy. The cost at the Salt Lake County Jail is equivalent to $92 per day for each inmate.

State Sen Todd Weiler, R-Wood Cross, who is chairman of the Senate Judiciary, Law Enforcement, and Criminal Justice Committee, said last week he is not aware of details regarding a settlement agreement, although he may get such information in coming weeks.

"I'm encouraged to see progress on a settlement agreement," Weiler said of the ongoing negotiations. "It's imperative that people with disabilities have accommodations within the state judicial system."

In April, the state sought dismissal of the suit based on a new outreach program. But federal Judge Robert Shelby denied the motion.

Alan Sullivan, an attorney representing the Disability Law Center, told Shelby that the launch of a new outreach program in which inmates deemed incompetent are being evaluated by social workers in the jail does not mean they are getting treatment.

"[It] doesn't even pretend to be a treatment program," Sullivan said. "It's a monitoring program."

But Parker Douglas, chief federal deputy for the Utah attorney general's office, said jail inmates' mental-health needs are being met adequately through the program.

"They claim that all people do in jail is sit there," Douglas said, "and that's just not true."

Nationally, most states have wait times for treatment of less than 30 days, while several states have requirements that mentally incompetent inmates are transferred to a state hospital within seven days.