This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

St. George • Nearly a decade before 21-year-old Matthew Shepard was beaten, tortured and left to die in a Wyoming field, there was Gordon Ray Church.

Just like Shepard, Church was brutally killed primarily because his attackers believed he was gay.

The 28-year-old Southern Utah University student was taken by two recent parolees to a remote location in Millard County, where the men attached jumper cables to his testicles, used the car battery to shock him and then sodomized Church with a tire iron to the extent that his liver was pierced. They then beat Church to death with a car jack before burying him in a shallow grave.

Unlike Shepard, Church's killing was a decade too early to receive national recognition as an LGBT hate crime. There were no hate crime prevention acts or foundations created in his name.

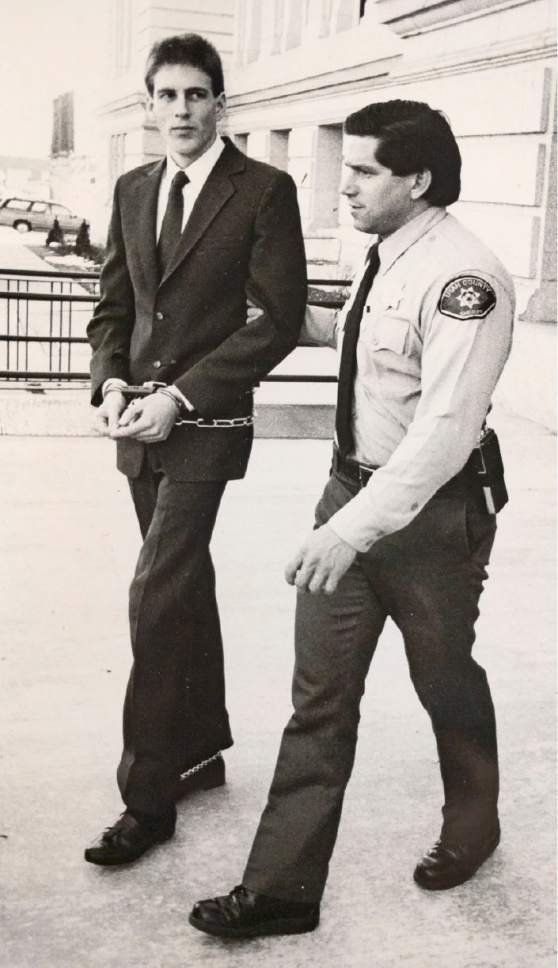

In two separate trials, Michael Anthony Archuleta and Lance Conway Wood were both convicted of capital murder. Wood was sentenced to life in prison, while Archuleta, who was believed to have been the primary instigator, was sentenced to death.

More than 28 years later, Wood remains incarcerated in an Oregon prison while Archuleta is one of the nine men on Utah's death row awaiting execution by lethal injection.

After growing up in a devout LDS family in the small community of Delta, he was eager to explore his interests and build his own life as a student at SUU, reported the Spectrum & Daily News (http://bit.ly/2ibnWhT).

"We got the sense that his parents were disappointed but supportive to an extent," Kathy Long said. Long, who is an employee of The Spectrum & Daily News, developed a close friendship with Church through mutual friends while they were both in college. The pair would meet to smoke cigarettes and drink coffee outside of the Sharwan Smith Student Center after their morning classes.

Church, Long and two other friends were actually planning to meet for a last-minute dinner before everyone returned to their family homes for the Thanksgiving holiday. The plan was to meet at an apartment before heading to the restaurant in the early evening on Nov. 22, 1988.

First, Church just had to stop by the 7-Eleven on South Main Street to pick-up a pack of cigarettes and then he'd be right over to head to dinner, Long recounted.

But the predetermined meeting time passed and Church wasn't there. Two hours passed and there was still no sign of their friend. There was no answer when they called his house, so they went to dinner without him. While they didn't think to contact police, they were concerned because it wasn't like him to just not show up without an explanation.

"He just never showed up," Long reminisced. "It was strange because he had always been so dependable. That's one of the reasons why we waited so long."

Long would learn the next morning that Church's body had been found approximately 76 miles away off a deserted dirt road in Millard County.

Archuleta and Wood were never supposed to be living together. The two men had both been recently released from prison. Archuleta, who was 26, for a drug offense in Utah County, while 20-year-old Wood had served one year after he was convicted of stealing and crashing a motorcycle in Bountiful when he was 18.

Despite the fact that it violated both of their parole guidelines, the two parolees had been living in an apartment in Cedar City with their respective girlfriends for a few weeks.

On the evening of Nov. 22, the two men were bored. Wood's girlfriend was out of town for a few days, so the pair headed out to the 7-Eleven to get a soda before adding a few ounces of whiskey to each of their drinks.

That's when they met Church.

According to testimony from Wood's 1989 trial, the two men just started a conversation with Church while he sat in the parking lot in his white Ford Thunderbird.

The three men then decided to cruise down Main Street in Church's car. They even pulled over to chat with two young women during their drive, according to witness testimony during the trial.

They then drove to a secluded area in Cedar Canyon as the sun began to set. As they parked the car, Church revealed to his new companions that he was homosexual.

At this point, Wood and Archuleta's versions of what transpired differ drastically. Wood alleged that the two men had previously made the decision to rob Church because "he was a homosexual," while Archuleta asserted there had been no such conversation.

This is not the only place their stories differ. According to Archuleta, Church offered to engage in anal sex after he told them he was gay. He even asked him to use a condom, but Archuleta changed his mind and stopped halfway through. Wood told police that Archuleta sexually assaulted Church with a knife to his throat before turning to Wood and asking if he "wanted any."

What is clear is that the two men then began to attack Church. At only 5-foot-5 and approximately 150 pounds, Church was fairly easy for the two men to tackle to the ground following the sexual assault, breaking his arm and the lower left portion of his jaw in the process. Trial prosecutors later established that Wood used a knife held in a scabbard on his belt to cut Church across the throat, resulting in a superficial wound in the shape of an "x."

During the trial, Wood detailed how Archuleta then bound Church with tire chains and a bungee cord found in the trunk of his own car. While he was still conscious, Church was shoved into the trunk of the car and trapped there as the two men drove north on Interstate 15 for nearly 80 miles. They stopped nearly an hour later in a secluded area in Millard County known as Dog Valley.

The brutality only continued in the new, deserted location. After removing Church from the trunk, battery cable clamps were attached to him and to the car battery in an attempt to electrocute him before they beat him on the head with a tire jack and tire iron, according to trial records. Injuries to Church's skull were so severe that a medical examiner later testified that they appeared similar to if his head had been run over by a truck.

His lifeless, mangled body was then dragged up a hillside and buried in a shallow grave covered by twisted dead tree branches.

With Wood at the wheel, according to trial records, the two men left the crime scene and headed north on the I-15 before abandoning Church's car in Salt Lake City. With their pants covered in Church's blood, they headed to a local thrift store to buy some clean clothes. Archuleta told the clerk that the blood stains were from a rabbit hunting trip the night before.

After dumping their clothes in a drainage ditch in Salt Lake County, Archuleta and Wood hitchhiked back to Cedar City. They were home free.

But then Wood panicked.

Wood told his parole officer how he had witnessed Archuleta kill someone less than a day after they had left Church's body buried in Dog Valley.

In the early hours on Nov. 24, Wood, accompanied by his parole officer and the Iron County sheriff and attorney, returned to the scene of the crime. Wood even retold the story to Millard County officials over breakfast after they realized that the actual murder had occurred in Millard County.

Millard County Sheriff Robert Dekker, who was heavily involved in the investigation and prosecution process, still remembers being guided to the body by Wood.

"You don't ever like to deal with those kind of things, but it's a part of the job," he said. "It was right before Thanksgiving, so it was a difficult time. It was a difficult case to investigate. It was a very brutal crime."

Wood was initially arrested as a material witness due to concerns that he'd try to run off, Dekker recounted. It didn't take long for investigators to figure out that Wood had done much more than just watch Archuleta kill Church after reviewing the crime scene.

"The physical evidence at the scene — especially the blood splatter — gave him away," Dekker said. "And the way he was talking. It was obvious that he was involved from the get-go."

Archuleta was arrested shortly after in Cedar City on a parole hold.

Millard County isn't exactly a hot spot for violent crimes. FBI crime data indicates just one or two murders every few years. In 1988, the population of the small county was barely 11,700. All of these factors made the brutal murder of Church particularly difficult for the community. Church's family, which lived in Delta, was well known throughout the county, Dekker remembered.

"Some people were affected by it really hard. The Church family was respected really well in Delta. They were a well-known family," he said.

The crime took a large enough toll on the community that a change of venue was granted for both Archuleta and Wood's trial. So the Millard County Sheriff and the County Attorney packed up their offices and moved up to Utah County for Archuleta's trial, barely 13 months after the murder, in December 1989.

Wood's trial immediately followed in January 1990.

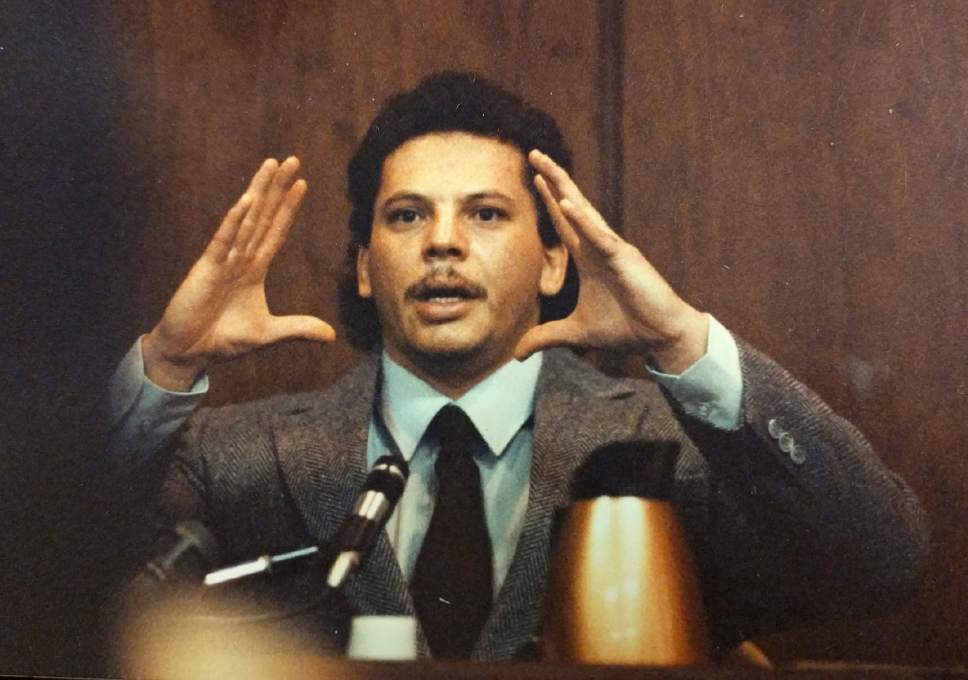

In both trials, the two defendants kept pushing the responsibility on to the other. Archuleta's attorneys attempted to shove the blame on Wood, while Wood's defense team portrayed Archuleta as a seasoned criminal who acted as the ringleader throughout the entire assault while Wood waited quietly in the car.

Dekker saw right through their defenses.

"We had blood on both of them, on both of their clothing," he said. "They would shift responsibility back to the other guy, but we had a lot of physical evidence from the crime scene that tied both of them back to it."

Church's blood was found on the back of Archuleta's jacket and on Wood's shoes. A strand of Church's hair was wrapped around Wood's shoelaces. A medical examiner testified that the cuts on Church's back were likely caused by a dull-tipped instrument similar to the red-handled side cutters found in Wood's jeans. The front of Archuleta's pants, which were recovered from the Salt Lake drainage ditch, were drenched in Church's blood.

Both men faced a long list of charges on top of the one count for the murder, including aggravated sexual assault and kidnapping. But a hate crime charge never made the list. Prosecutors hardly attempted to prove that the crime was motivated by Church's sexual orientation because hate crime laws wouldn't even exist until three years later in 1992.

The evidence was there, though. During Archuleta's trial, Millard Sheriff's Sgt. Charles Stewart testified that Wood had told him during a police interview that Archuleta said he wanted to rob Church "because he was a homosexual."

In the second trial, Wood testified that "Mike (Archuleta) said Gordon was a faggot and he wanted to rob him of his money."

Long even recalled investigators telling her that a witness had heard Archuleta say, "Let's get the fag" inside of the 7-Eleven. No other record of this exchange was found.

"They couldn't charge it as a hate crime because it just didn't exist at that point, so that part of Gordon's murder just got lost," she said. "It should have been a real flashpoint in gay rights or hate crimes if it had been dealt with a little bit differently. The context of the time really didn't allow for that, though."

Ultimately, the prosecution's attempt to portray Archuleta as the main instigator worked. He was sentenced to death, while Wood received a lesser sentence of life in prison.

Dekker believes the drastic differences in sentencing had more to do with their physical appearances than their actual roles in the crimes. Archuleta, a Hispanic Catholic, seemed to fit the look of a murderer better with prison tattoos covering his neck, Dekker recalled.

"Wood (during the penalty phase) was a good Mormon boy who had his old (Boy Scout) master and bishop come to testify how good of a kid he was," he said. "Archuleta didn't have that. He was an adopted kid (though Wood was also adopted). I think that definitely had an effect on the jury."

At his sentencing, family members of the then-22-year-old Wood said that he had a strong desire to be rehabilitated, finish high school and to even get married someday.

With his life sentence, though, he had no choice but to accomplish it all from within prison walls.

Wood was initially held in the Utah State Prison, but was transferred to an Idaho facility under the Interstate Compact, which allows for the transfer of inmates between states.

There, Wood managed to accomplish one of his goals when he married Renee McKenzie, the ex-wife of an Idaho state senator. She eventually left him to marry the convicted murderer.

McKenzie was appointed to help Wood with his court paperwork while working as a paralegal for her former husband's law firm in 2012. She had agreed to Wood's request to help him fight a federal case against an employee of the Idaho Department of Corrections who accused him of sexual harassment, according to a complaint filed in the U.S. District Court in Portland in 2014. Wood was accused of having inappropriate relations with four different prison employees.

But the pair began to develop romantic feelings as they worked on preparing Wood's defense, the court document detailed. The relationship went unmonitored by prison officials as they believed McKenzie was working under the supervision of a lawyer. Their affair was discovered in 2013 when a prison staff member read a letter McKenzie wrote to Wood that revealed their relationship was no longer strictly professional.

McKenzie was later investigated by the county for practicing law without a license, but no charges were ever pressed.

Wood was transferred to an Oregon facility in 2013, which McKenzie said was a calculated move to keep the couple separated. They ultimately married in 2015 before filing a federal lawsuit seeking $50 million in punitive and compensatory damages based on claims that they faced retaliation from the Idaho Department of Corrections staff for their continued work to uncover corruption within the prison system.

The case is still pending at this time. Wood, now 48, is not currently scheduled for a future parole hearing.

Archuleta hasn't stopped fighting his death sentence since the jury's decision was read in the Fourth District Court 27 years ago.

In nearly three decades, Archuleta has come close to facing his looming execution only once in 2012. His appeal on the grounds that his trial and subsequent appeals counsel was ineffective was rejected by the Utah Supreme Court in 2011. A federal judge ultimately halted the firing squad execution after Archuleta decided to pursue an appeal in federal court.

While that appeal was also rejected, Archuleta's case is continuing to unfold as he remains on death row in the Utah State Prison. A new brief appealing a Fourth District Court's decision to dismiss a previous appeals claim alleging that he was ineligible for execution because he was "intellectually disabled" was submitted on Dec. 19.

"We have presented evidence to the court that Michael does have an intellectual disability, therefore he has a merited claim that he should be exempt from execution," David Christensen, the lead attorney in the case from the Utah Federal Defenders Office, said.

In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that defendants who are found to be intellectually disabled could not be sentenced to the death penalty as it was considered to be cruel and unusual punishment because the deficiencies generally related with disabilities are known to reduce their level of culpability.

The decision to not bring attention to Archuleta's alleged intellectual disability during the initial trial wasn't an oversight by his trial counsel as it wasn't even a real claim at that point.

Court documents indicate that Archuleta's mental health history was investigated extensively during the trial preparation. A board-certified forensic psychologist did not uncover any brain damage or recommend any possible lines of defense based on his mental health or intellectual levels.

But Archuleta did have a known history of both physical and mental health issues. He was born in what court documents describe as "deplorable conditions" to a 16-year-old until he came in contact with the Charitable Trust and Custody Services of the LDS church. The 3-year-old was covered in cigarette burns and was in a "filthy state" when he was taken into their custody, according to court documents. He was placed with a foster family, who eventually adopted him.

The problems continued throughout Archuleta's youth as he suffered from ADHD and spent a significant time in the Utah State Hospital and mental health facilities, where he may have been sexually assaulted. A second post-conviction evaluation in 2006 concluded that Archuleta suffered from a neurocognitive impairment that heavily affected his ability to write and spell.

Andrew Peterson, with the appeals division at the Utah Attorney General's Office, argued that it just isn't enough to prove Archuleta was actually intellectually disabled.

"His attorney sort of guessed that he is," he said.

A previous request to have Archuleta re-evaluated during district court proceedings was denied on the grounds that that the information should have been presented to the court sooner, but instead his attorneys had been "sitting on it," Peterson explained.

"The court wouldn't even allow the expert to go into the prison to evaluate him because he's not even allowed to present all of the information because of the timeliness issue," Peterson said.

The intellectual disability claim was actually tacked on to an earlier appeal to the federal court, but federal law prohibits the court from considering any claim that hasn't already been presented to the previous courts. The matter will now be considered by the Utah Supreme Court before returning to the federal court.

Peterson speculated that the claim was only brought forward to further delay the execution.

As to if — or when — Archuleta will ever face execution, Peterson estimated that he could still have years left of appeals if that's the route he wants to take.

But Dekker is hopeful that he will one day face his punishment for the nearly 30-year-old crime.

"I'm still waiting for that phone call to come up and witness that execution," he said.