This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Josh Schiffman likes to think of the tumor-suppressing protein p53 as a superhero in a bright red cape.

It swoops in whenever there is DNA damage and fixes or eliminates the problem in an attempt to keep the body healthy. Most mammals, from humans to elephants, have some p53. But elephants — which rarely get cancer — have many more copies, Schiffman said, and they're stronger.

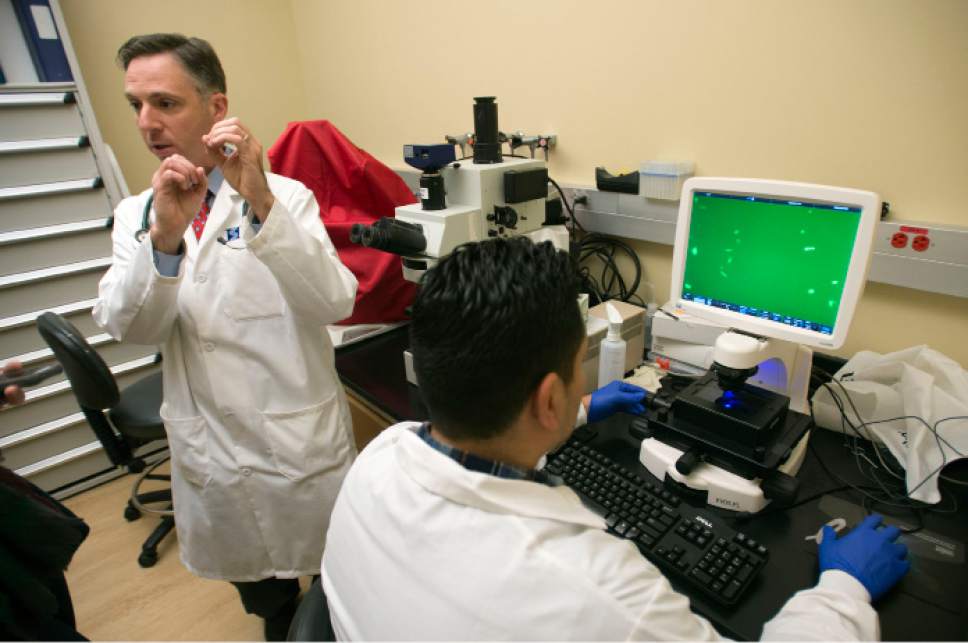

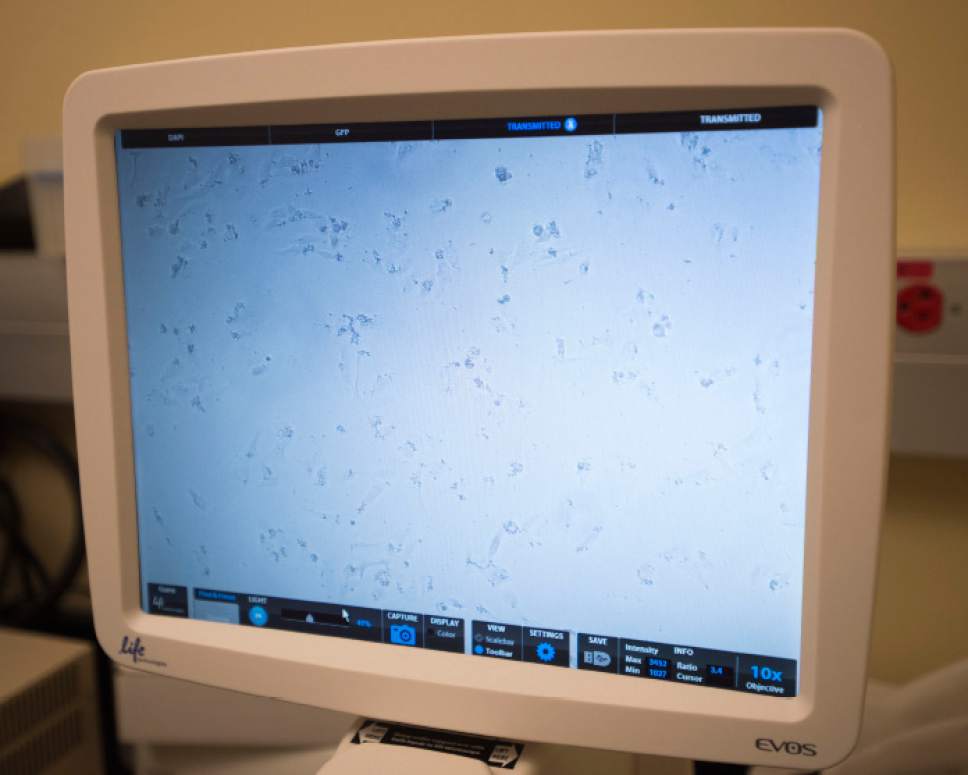

That's why it's such a thrill watching human cancer cells injected with synthetic elephant p53 shrivel up and explode in a dish.

"I'm so excited by this potential," a pediatric oncologist and medical director of the shared High Risk Pediatric Cancer Clinic at Intermountain's Primary Children's Hospital and University of Utah's Huntsman Cancer Institute.

The idea to study elephant DNA came to Schiffman about five years ago. In 2015, he showed that the animal's extra, slightly different copies of p53 make them cancer resistant. Elephants have 40 copies.

And this year, he plans to submit a paper for publication showing the impact elephant p53 can have on human cancer cells. It's quickly destroying the cells in the seven cancers, including lung, breast and bone, he's tested it on so far, he said.

Most people have just two copies of p53, and Schiffman said p53 is inactive in more than half of all human cancers.

"Nature has had millions of years to figure this out," he said. "What we're doing is learning from nature."

Schiffman cautioned that he has not found the cure for cancer, but that early results are promising. The elephant p53 "is working and it's working better than we ever could have imagined," he said.

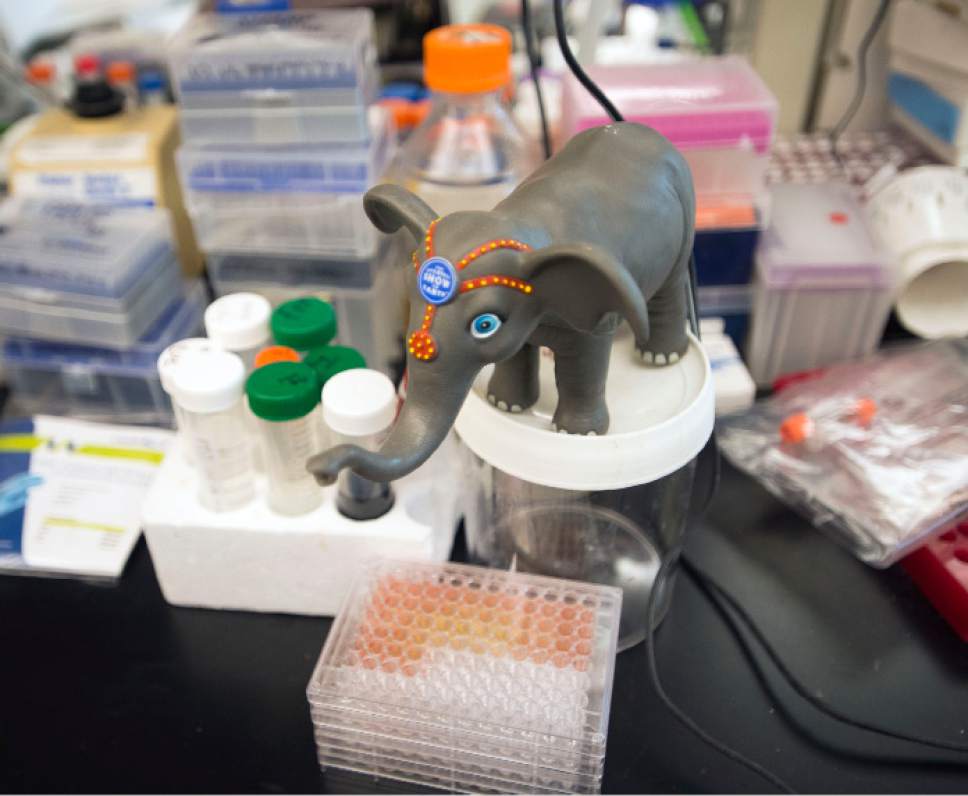

Initially, Schiffman was using a small amount of blood from elephants at the Hogle Zoo and Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, but researchers have developed a synthetic form of p53 and are injecting that into the human cancer cells in dishes.

Currently, he's working with Avi Schroeder, an assistant chemical engineering professor at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, to manufacture the protein in nanoparticles to begin preclinical testing. Tinier than the width of a human hair, the tennis ball-shape nanoparticles would deliver the protein to the cancerous tumor, likely through an IV to start.

It's a technology already used in chemotherapy, which Schiffman said will help with Food and Drug Administration approval when the time comes.

Schiffman said his team already is developing a test for mice, and hope to test it in pet dogs with cancer as well. Testing in humans would come after that: a feat that could be accomplished in three years if Schiffman can secure the $20 million he believes he needs to pay for the trials.

In preparation for those human clinical tests, Schiffman has formed a spinoff company, PEEL Therapeutics. Peel is the Hebrew word for elephant — appropriate terminology given Schroeder's role in the endeavor.

Until then, Schiffman takes time each morning to watch a time-lapse video of the human cancer cells dying in their dishes, envisioning a time when elephant p53 could help even one person. As a cancer survivor himself — he had Hodgkin lymphoma when he was 15 — he knows what that could mean.

"I'm on a quest to get rid of cancer," he said. "I think we're on the way and I think the elephants are going to lead us there."

astuckey@sltrib.com

Twitter @alexdstuckey