This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The second desk drawer on the right in John Opitz's study isn't lined with the typical pens, pencils and Post-it notes: It's lined with eggs.

Twenty-two eggs, to be exact, laid by his bird, Darwin, who is just one of myriad animals that roam Opitz's home, his love of zoology and biology brought to life.

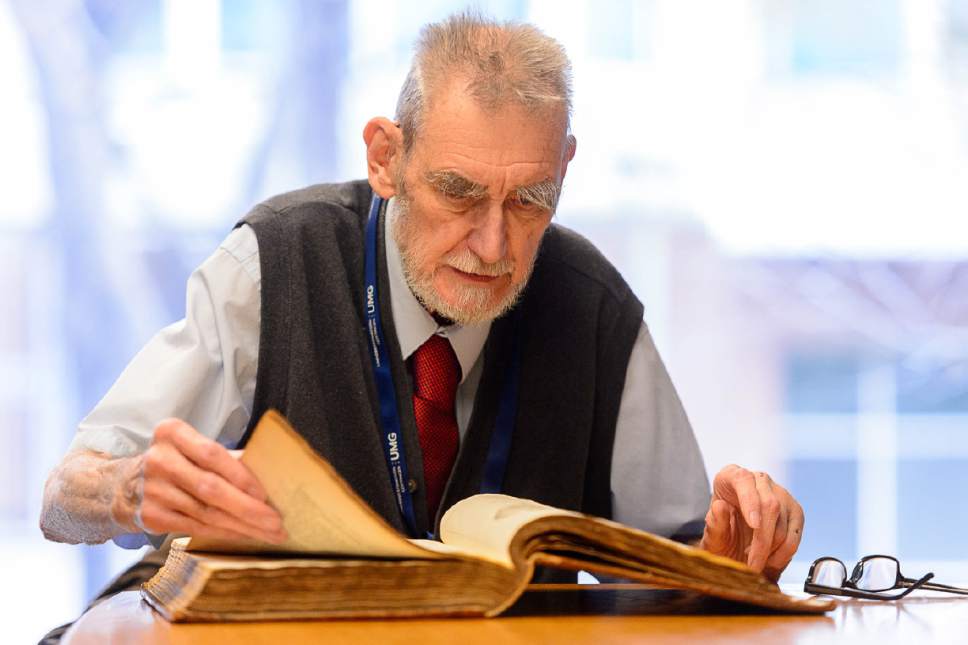

"I always had a strong interest in nature," said Opitz, 81.

That love began as a child growing up in war-torn Germany, where he wandered the woods behind his home studying plants, animals and fossils.

It spawned into a lifetime of studying pediatrics and human genetic disorders — at the University of Utah and in other places — culminating in his receipt this month of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for his "outstanding contributions in the field of medical genetics," according to a letter sent to Opitz from the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany in Los Angeles.

To most people, this would be the perfect bookend to a career in pediatrics. But Opitz isn't most people.

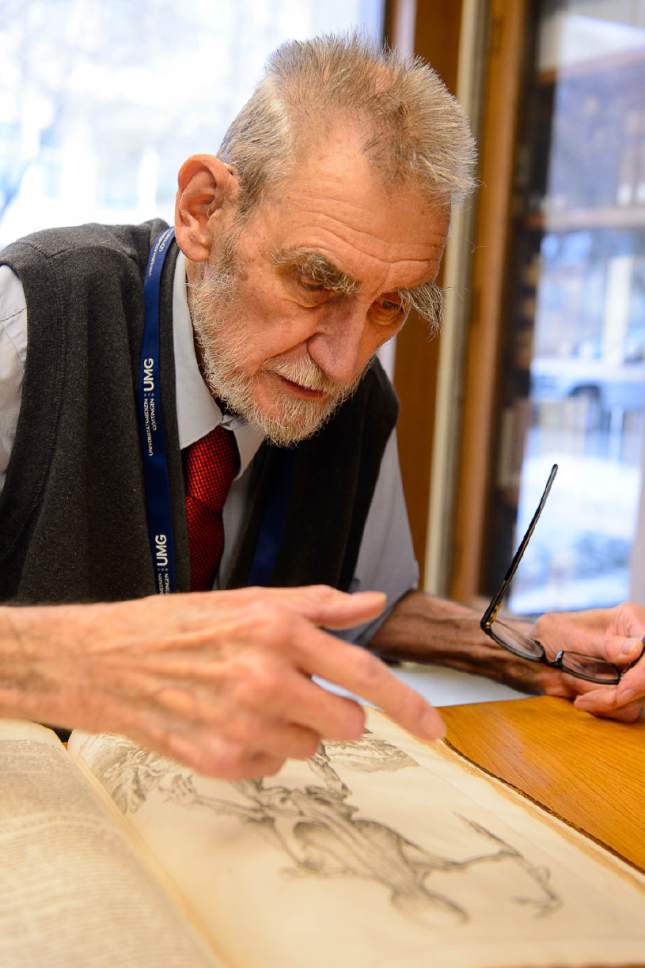

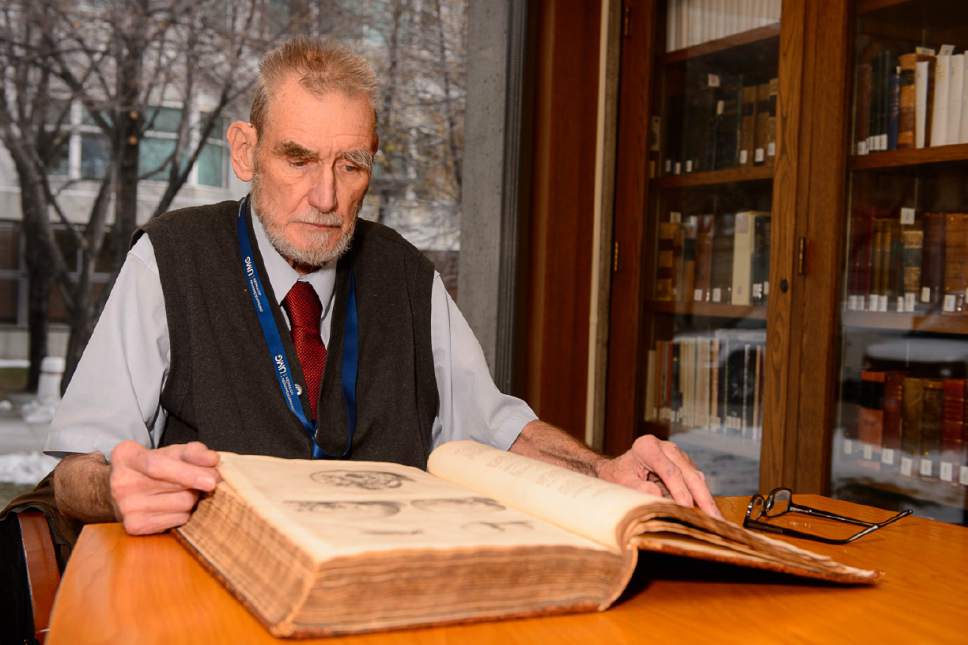

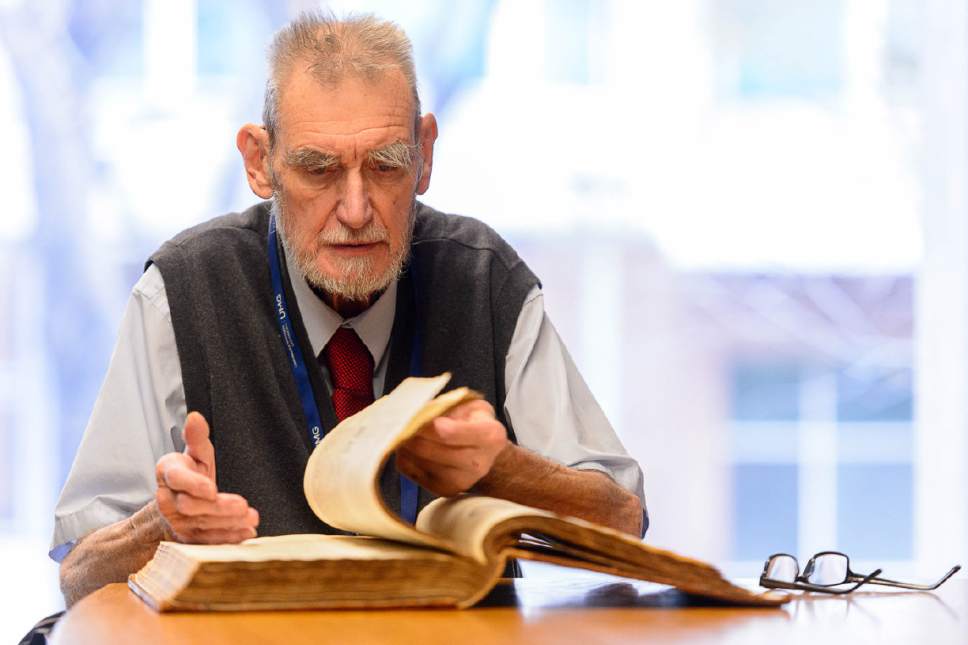

He plans to continue his research at the U. until he drops dead. Or until macular degeneration takes his eyesight.

He's been "given permission to continue, even after age 81," he said, "to work in the department [of pediatrics] to finish my life's work on trying to ... throw light on the relationship between human development and evolution."

—

A reformed class clown • If Opitz and his mother hadn't moved to the U.S. in 1950, he's confident his hands would have spent 50 years laying brick instead of healing children.

Opitz was 15 when the two moved to Iowa — his father having died almost 10 years earlier — but he already had been expelled from school three times in Germany.

"I was the class joker," he said. "I didn't know how to act."

He attributes this behavior to a life that, until that point, had been filled with chaos.

His home country had been ravaged by two World Wars. His father was dead, he said, and he was separated from his mother after contracting tuberculosis.

"I was in such pathological shape, psychologically speaking," he said, "that I never would have amounted to anything in Germany."

But when they arrived in Iowa, Opitz said he felt like a real human being for the first time. Gone were the daily bombings and rubble, replaced with hospitality, peace, kindness.

"It was a dramatic change," Opitz said. "My adaptation to live in the U.S. was a bit of an adventure: I experienced nothing like this ever in Germany."

He entered American high school as a sophomore and, at the same time, became acquainted with Emil Witschi, a zoologist and genetics expert who taught at the University of Iowa.

He started working in Witschi's laboratory, first as an animal caretaker and then as a lab technician, before enrolling in medical school in 1955.

Though Opitz loved zoology and biology, he decided to focus on pediatrics.

The transition from zoology to pediatrics is obvious, Optiz said, because pediatrics is zoology of the child. But that's not the reason he landed in that field.

"After we got to Iowa City, my mother was a secretary in the pediatrics department and she said, 'Of course you'll go into pediatrics,' " Opitz said. "And I said, 'yes, ma'am.' "

—

Personalized care • After graduating from medical school in 1959, Opitz ended up at the University of Wisconsin and began his work defining and documenting genetic syndromes.

By studying the intersection between genetic, evolutionary and developmental factors involved in abnormal human development, he was able to discover at least 50 "Opitz syndromes," said Ed Clark, chairman of the U.'s Department of Pediatrics.

For example, he identified the Opitz G/BBB syndrome is a condition that can cause physical abnormalities such as heart defects and wide-spaced eyes.

Clark said this work is one of the major reasons he recruited Opitz to the U. in 1996 to be a professor as well as a clinician at Primary Children's Hospital.

"By bringing him into our university," Clark said, "we have a powerful scientist, clinician and scholar to advance our understanding of human genetics."

Opitz's love for history — developed when he learned to read from a history textbook as a young child — helped him in this work, Clark said.

"Because of his scholarly studies of historical information, he has been able to bring the past together with the molecular age in a way that's hard to believe anyone else could," Clark said.

He melds historical insight "together with modern molecular and developmental biology to give a unique understanding of the clinical conditions we deal with in pediatrics."

And for about 20 years, families with these particular conditions came from all over the world to see him.

"We're so fortunate to have him both here at the university in pediatrics and in Utah because he has attracted remarkable people from around the word who come here to work with him," Clark said.

The work stretching across his lifetime has garnered him the Officer's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, "the highest tribute that Germany can pay to individuals.

It "recognizes those who have had a profound impact on building ties between Germany and other nations," according to the German Missions in the United States website.

Jürgen Spranger, emeritus chairman of pediatrics at the University of Mainz in Germany, nominated Opitz for the award. He met Opitz in 1969 at an International Conference on Birth Defects in Baltimore, he said, and they've remained in contact ever since.

"Gifted with a sharp eye, utter carefulness, bedazzling memory, ability to focus on the essential facet, immense working power and incessant curiosity, he delineated so many new conditions that he had to use his patient's initials to name them," Spranger said. "He used a fine brush to examine his patients. And he used a very fine pen to describe their illnesses."

Opitz no longer is practicing medicine, but Clark said he's keeping Opitz on at the U. to continue studying of the intersection of human development and evolution.

And when he's not doing that, he's spending time in his book-lined study, Darwin screeching at the magpies outside the window.

But don't forget about his dogs and cats, who fiercely guard his books from harm.

"They keep the bookworms out," he said with a laugh.

Twitter @alexdstuckey