This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

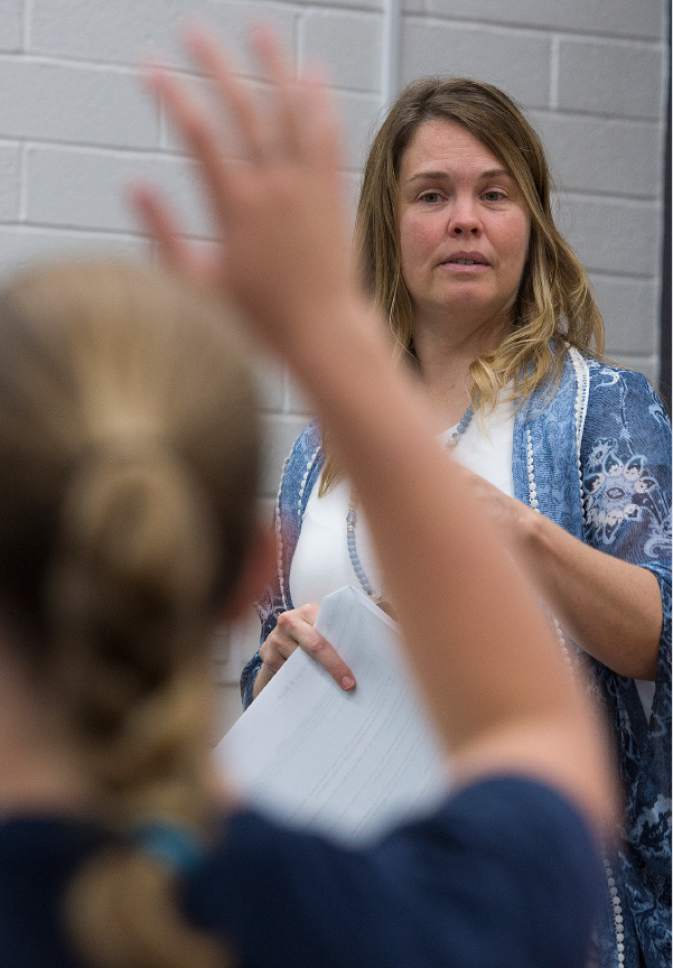

St. George • Sasha Trae stood in a Dixie State University gymnasium, the sound of feet thumping against punching bags and triumphant yells of "No!" rising up around her.

Trae — her shirt declaring "I always get consent" — wandered around the blue and red mats spread on the floor, shouting instructions and encouragement to about 15 women learning how to defend themselves against an attacker.

Self-defense is just part of Trae's class, the Personal Safety Coalition, a staple for students at Dixie State since the 1990s. Professor Tim Eicher, who is now retired, created it because he was "astonished" by how many of his students were writing papers about being sexually assaulted.

But Dixie, then a two-year state college, had almost no resources for victims, Eicher said.

There were no psychological or Title IX services, he said. Title IX governs university responses to sex-based discrimination, harassment and assault.

Since 1976, colleges have been required to designate a coordinator who ensures they comply with the federal law. Dixie didn't hire its first full-time Title IX coordinator until January 2015.

"I've felt like the lonely voice howling in the wind," Eicher said. "I was like, 'Let's make this a campus culture of no tolerance for sexual assault.' We never ever got to that level."

But Dixie and other universities across the country were prompted to begin changing in 2011, when President Barack Obama urged colleges to strengthen their Title IX policies and improve how they investigate and adjudicate sexual assaults of their students.

Cindy Cole, who became Dixie's second Title IX coordinator in the fall of 2015, has been revamping the school's investigation and disciplinary policies, as well as educating students on consent and where to report an assault.

She's also making sure students understand that they can come to her to get help with extended deadlines for assignments, counseling or changes in their classes and housing after an alleged assault or harassment.

Student access to counseling is limited and there's no campus victim advocate, other than a community advocate who visits Dixie State once a week for two hours. Some students who report sexual assaults have later said they did not feel taken seriously by the school, advocates say, but the changes are a step in the right direction.

"The progress [Dixie] is making, you have to applaud them," said Lindsey Boyer, executive director of the Dove Center, which provides services to sexual assault victims in the area. "They have some good things in place now. Even if they're not up to the standards people think they're supposed to be, it's important to acknowledge the steps they're taking."

—

A hidden problem • It's unknown how many Dixie State students reported sexual assaults to the school before January 2015.

Title IX fell under the umbrella of the university's human resources department, and its director — who oversaw equal employment and affirmative action — also was designated as Title IX coordinator.

Students who wanted to report assaults were directed to Del Beatty, the dean of students. Beatty would investigate a complaint and, if he determined a student was responsible for an attack, either immediately determine sanctions or refer it to a disciplinary committee, he said in an interview.

That committee would make a penalty recommendation, and Beatty would decide whether to issue a sanction.

Between 2010 and 2014, one student was sanctioned for a sexual assault, according to a document provided to The Salt Lake Tribune through an open-records request. That student was expelled.

It was the only sexual-assault report that Beatty recorded during that period. He did not log complaints that came into his office unless the alleged perpetrator was found responsible, university spokeswoman Jyl Hall said.

Beatty told The Tribune he did keep a file on each accusation. But he did not provide The Tribune a specific number, saying only that there were "very few."

Dixie officials say the school and the community are safe areas, but concede that sexual assault is underreported.

"I know there has to be [rapes] but we usually find out after the student graduates," said Don Reid, the university's public safety director.

"They call back to the dean of students [and say,] 'I was raped at Dixie. I think you need to know about this guy,'" Reid said. "I don't doubt we have cases, but if they don't get reported to us, we can't investigate."

For students who do report now, the creation of the Title IX position has dramatically changed how the university responds.

Students report to the Title IX office instead of Beatty. Staff in the office investigate. And in a policy change Cole prompted last year, Beatty no longer has the final say on whether a student is responsible for an assault or the sanctions.

Instead, investigators make a recommendation to a disciplinary panel, which then decides any punishment. There also is an appeals process, Cole said.

Reid said he "has been doing cartwheels" since the school launched its Title IX office.

"I think in the past, [Dixie State] hadn't hired a Title IX person because [officials] didn't understand it completely," he said.

Reid told The Tribune that he believed it was "difficult for [Beatty] to make disciplinary decisions" in cases of sexual assault.

In response, Beatty said the school takes "all reports very seriously" and pointed to the new system in a statement.

"Every single time a report is made, the Title IX office conducts a thorough investigation and appropriate sanctions, up to and including dismissal from DSU, are administered," Beatty said.

—

'You come to an agreement' • Cole meets twice a month with a committee that includes campus police, Beatty and Dixie's general counsel to discuss potential dangers on campus, including sexual assault complaints.

The meetings were started by Cynthia Kimball Davis, an adjunct professor of English as a Second Language at Dixie who then became the school's first Title IX coordinator. She was in the job for about six months and now works at Southern Utah University. She declined to be interviewed.

Cole, a former California prosecutor and rape crisis advocacy manager, credits her with setting up the office.

Reid said the twice-monthly meetings have led to positive changes. He and Cole said Beatty and others on the committee sometimes must be convinced action is needed after an allegation is made.

"It's like any committee or group: One person may not think something needs to be done, but when you talk it out, you come to an agreement," Cole said. "We get great input and ideas from everybody."

Although the meetings are improving collaboration, Cole said, there was at least one instance where campus police did not inform her office of a sexual assault complaint, which she wants them to do.

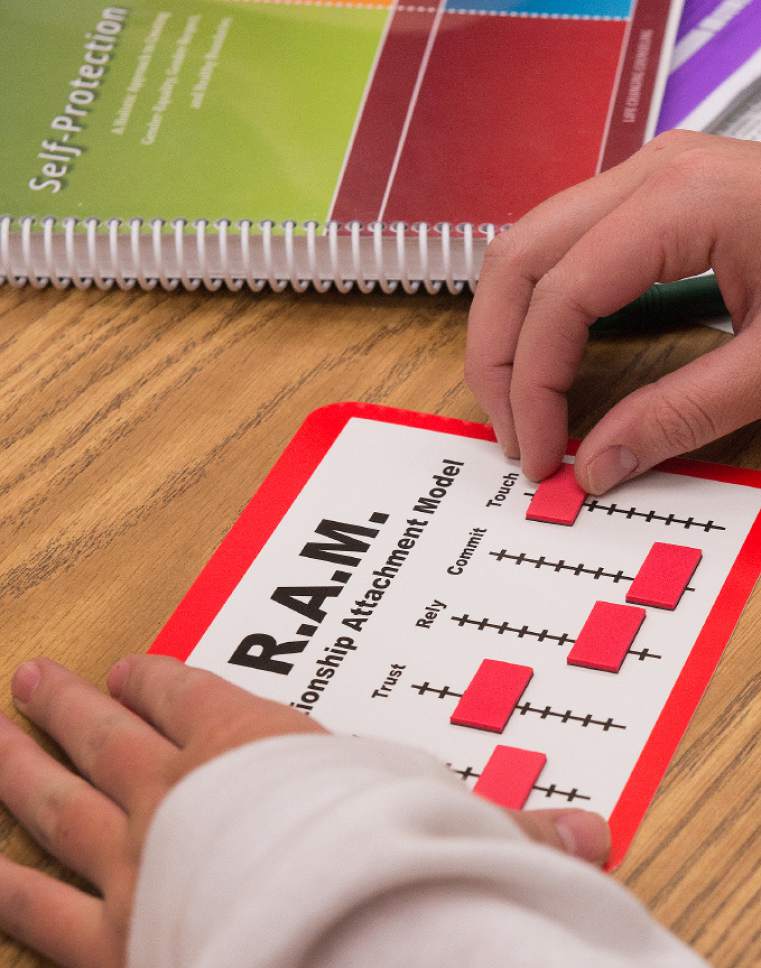

Using her background in criminal justice and victim advocacy, she's ensured all individuals involved in the Title IX process — from investigators to disciplinary panel members — are trained on how to speak to sexual assault victims and what questions to avoid.

She also has revamped how Title IX investigation reports are compiled, saying they previously were weak on analysis and reasoning. She speaks to classes and student organizations about her office's services, their reporting rights under Title IX and the definition of consent, she said.

Cole said students appeared wary of reporting to the school prior to her arrival — which is inherent with sexual assault — but she's seen a small increase in the number of students reporting to her office.

—

'Slowly changing' • Every Wednesday for two hours, Dove Center victim advocate Elizabeth Bluhm sits in a closet-size office waiting for a sexual assault victim to ask for help. She helps students navigate the process of reporting to the school, to the police or seeking mental health services.

Bluhm said demand for her help has been low, but it's a service students are still getting used to having. Her visits started less than two years ago, after the school's Title IX office opened.

Students do seek free counseling at the Dove Center, which is a walkable distance from campus, she said. Dixie State charges a $20 fee for each therapy session, which can be waived depending on circumstances. Cole said students are limited, with some exceptions, to six therapy sessions.

Some students seeking services tell center employees they don't know why or how to involve the school after a sexual assault, Bluhm said, often because their assault didn't occur within campus boundaries, campus police didn't respond to it or they were raped by someone who was not a student.

Under the Clery Act, a federal law meant to alert students to dangers on campus, Dixie reported five sexual assaults between 2010 and 2015. Yet the Clery data only includes assaults reported to have occurred on campus property or directly next to campus — on a public sidewalk or road.

Since Dixie is a commuter school, with on-campus housing for about 700 of its fewer than 9,000 students, most sexual assaults involving students happen off campus, Bluhm said.

Some students have told Bluhm they decided against reporting an assault to the school because they didn't want to be blamed or told they shouldn't have been drinking. Rumors that the school will respond by blaming victims have spread on campus, Bluhm said. At a screening of "The Hunting Ground" documentary on campus last year, she said, a student told the room she wouldn't report to the school because she "heard they don't take it seriously."

But Bluhm said Cole understands the challenge of improving the school's policies and approach. "I have a lot of confidence in [Cole] and what she's trying to do," Bluhm said.

And students are reporting to Bluhm and others at the Dove Center that their experiences with Cole have been great, she said.

In 2015, there were five reports of sexual assault to Cole's office, Hall said. And Cole tracks every report that comes in, she said, whether it's substantiated or not.

"I don't think students knew about the Title IX process before," Cole said. "I think that's slowly changing."

astuckey@sltrib.com Twitter @alexdstuckey