This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

If an elected official becomes incapacitated, Salt Lake County residents almost universally believe a process should exist to remove that person from office, according to a Salt Lake Tribune-Hinckley Institute of Politics poll.

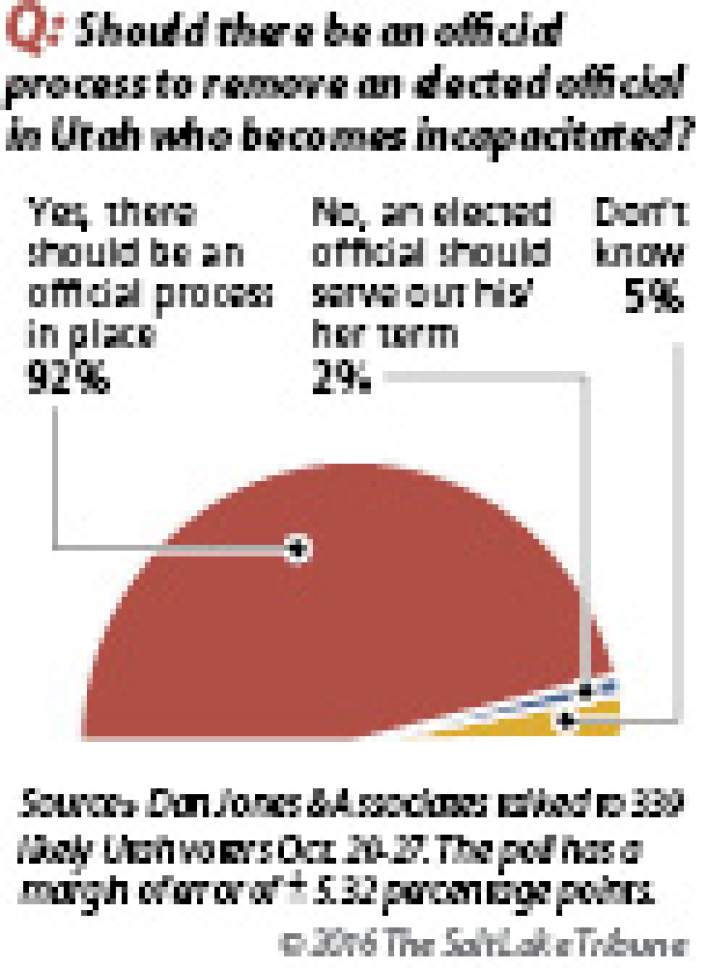

Out of 335 county residents questioned, 92 percent said there should be a way to remove an official who is unable to carry out an elected position because of diminished physical or mental abilities.

Nine people — 2 percent — said the official should serve through the elected term. Five percent were undecided.

As lopsided as those results are, they came as no surprise to county officials.

But from having dealt with the situation personally — recently watching Salt Lake County Recorder Gary Ott fumble through an agonizing defense of his office after an audit to address his declining cognitive skills — they know that finding a solution is simpler said than done.

"It's not an easy, straightforward answer like most people would like," said Republican Councilman Michael Jensen. "I'd put myself in that 'yes' category. I want my elected officials making decisions. That's why we elected them," he added. "But the problem is, statewide, how do you do it?"

The Legislature would have to amend state law to include a recall provision for all independently elected officials, like Ott, who has been a Republican recorder since 2002 and is answerable only to voters, not the mayor or the council.

But as the council's main legislative liaison, Jensen knows how hard it would be to craft an acceptable and widely applicable bill, especially because medical issues are involved.

He wondered: Who decides whether someone is mentally competent? How and when would consent be given — if at all — for someone to examine medical records? And what if accusations of incapacity are leveled for political reasons with trumped-up accusations?

"I'm not sure all cases would be as overt as the one we're facing now with the recorder," acknowledged Democratic Councilwoman Jenny Wilson. "Mental competence, if that's the term, is subjective. There's no easy way to define that well."

She interpreted the poll results as a clear sign that "the public is saying it's time for a change in this office and we'd like to see something happen. No one is comfortable with an elected official not living up to their commitment to their role."

Democratic county Mayor Ben McAdams, whose earlier review of the recorder's office found that no laws or ordinances were being violated, said the results "affirm where I am and many at the county are. We're frustrated at our limited ability to take any actions … at the lack of responsiveness in the recorder's office to legitimate concerns."

At the same time, all three county officials said separately, there's definitely a need for compassion in forging a law that protects public accountability and an individual's right to privacy.

"We want to be sensitive to the needs of someone experiencing a health crisis," McAdams said.

"A law should be crafted not necessarily in response to individual circumstances," he said, "but to something broad and workable for any future circumstances as well."

Efforts to contact Ott through his chief deputy, Julie Dole, were unsuccessful. But Dole echoed the thoughts of the other three county officials, saying, "If I had taken the poll, I'd be in the 92 percent as well."

She added, however, "Is there a definition for 'incapacitated' that would apply in [this type of] situation — and who determines it? I'm not in a position to evaluate Gary. He asked me to do a job, and I do it."

She questioned whether Councilman Randy Horiuchi, before he died last year, could have been considered incapacitated when he returned to the council after a stroke.

"Would you have taken Randy out?" Dole asked. "I don't think anyone can come up with something to determine competency that's fair."