This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The debate over the use of tax incentives to recruit new businesses, highlighted in West Jordan's controversial and ultimately unsuccessful courtship of a giant Facebook data center, appears likely to spill over into the 2017 Utah Legislature.

Sen. Howard Stephenson, R-Draper, said Wednesday he will introduce a bill next session that puts a 50 percent cap on the amount of new property taxes a school district can contribute to an economic-development area set up to attract companies with tax-incentive packages.

"This would set a bar beyond which [school districts] can't give any more away," Stephenson said in a Revenue and Taxation Interim Committee meeting. "Local school boards are uneducated on this. They give in to pressure, give away tax dollars dearly needed for schoolchildren."

Beyond that, Committee Chairman Daniel McCay, R-Riverton, decided the issue was too important and complex for an "abbreviated" discussion Wednesday at the end of a long meeting.

He plans to schedule an extensive committee discussion before the 2017 session to examine the issues in detail and "see if there's something we can do."

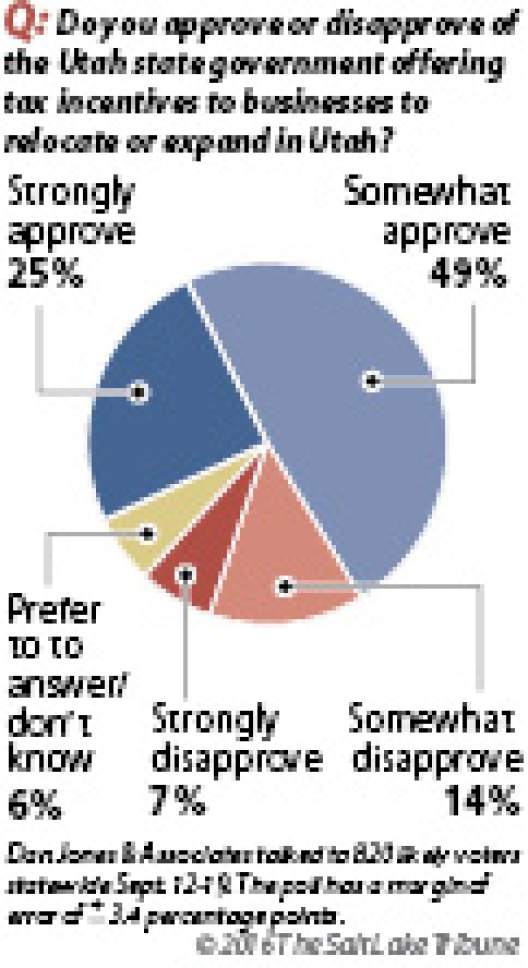

Utahns support offering tax incentives to attract new and expanding businesses to the state, according to a new Tribune-Hinckley Institute of Politics poll. The survey by Dan Jones & Associates said 74 percent favored such incentives, compared to just 21 percent opposed.

But the poll didn't address the most perplexing question: Just how much of an incentive is appropriate to lure a company to town? It's an issue that blew up as West Jordan and state economic development officials promoted a tax-incentive package worth up to $260 million to get Facebook to build six data-center buildings in the city.

Salt Lake County officials broke from the team recruitment effort, objecting that the tax incentive was far too large, especially given the few post-construction jobs it would create, 100 or so.

The county also opposed the size of West Jordan's proposed economic-development area (EDA) — up to 1,700 acres — far more than the 232 acres needed for the data centers.

Rep. Kim Coleman, R-West Jordan, said the county's objection to the size of the EDA seemed unfair.

Pointing to statistics provided by legislative staff about the amount of acreage in EDAs within each Salt Lake Valley city, she noted that older, more established cities have far more than West Jordan.

"There clearly is a disparity between how cities in your county were able to take advantage of economic-development areas," Coleman said. She said West Jordan was being denied equal treatment because it is developing later than other cities and should be allowed to catch up with more acreage targeting new businesses.

Stephenson, president of the Utah Taxpayers Association, said Coleman was "wrongheaded" in using acreage as a milepost for determining how local governments proceed with economic-development initiatives.

"I don't think I'm wrongheaded," she retorted. "My point is there was always a disparity" between the tax support West Jordan has gotten and what others have received — an issue overlooked in the county's arguments.

Stephenson said the state's system for offering incentives wrongly pits local governments against one another, giving companies a big negotiating edge.

"There should be regional consideration for where a new project goes, rather than them going city to city to find the weakest link, the city council that gives away the store," he said.

Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams agreed, maintaining a broader perspective is needed to take advantage of the state's sophisticated recruitment efforts and not allowing a site to be selected based on "pushing five cities into a mosh pit and telling them to negotiate for the state, losing [its expertise]."