This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

He's fine, Keno Day told her husband, Sam, while watching Facebook's chat panel for the green dot that would indicate her son was online and alive.

That was what they'd worked out, she and Jared: When he couldn't talk, he would log in, and she would know he was near his computer and out of harm's way.

Sam had read the morning of Aug. 6, 2011, that 30 U.S. servicemen had perished overnight when a Chinook helicopter was shot down in Afghanistan's Wardak Province. But a mother would have felt something, Keno thought, and she hadn't. Jared must be busy.

They waited all day for the green dot.

That evening, five men in U.S. Navy dress uniforms arrived at the doorstep of their Taylorsville home.

Blanding's Rodney and Betty Workman were prepared, at least, when the sailors came.

They'd been awakened that morning by a 4:30 a.m. call from the wife of their son Jason. Betty knew as soon as she saw the caller ID that the worst had happened. She could bring herself to answer only after her husband insisted.

Maybe it was shock, or having had to assume a brave face for their daughter-in-law, but the Workmans were strangely calm that day, Betty said.

Their son Corey came over, and the three of them set about making the types of phone calls and arrangements that more than 5,000 U.S. families have had to make since the Twin Towers fell and the U.S. went to war in the Middle East.

A light has been shone on Gold Star families in recent weeks as Democratic National Convention speakers Khizr and Ghazala Khan — the parents of a U.S. Army captain killed in the Iraq War — have feuded with Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump over, among other things, the meaning of sacrifice.

But the job of remembering the two dozen Utahns who died during Operation Enduring Freedom and dozens more lost to the Iraq War still falls to those Utahns' friends, families and fellow service members.

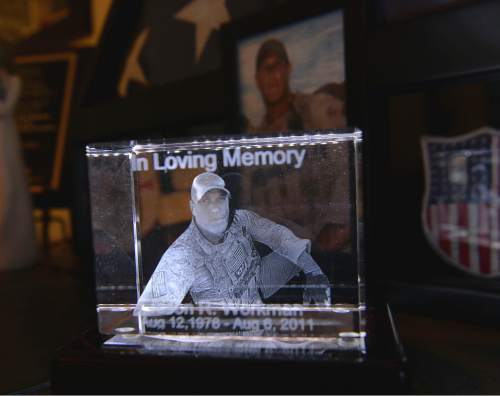

It's been five years since Workman and Day, assigned to a group popularly known as SEAL Team Six, sat aboard a Chinook as a rocket-propelled grenade hit one of its rotary blades and sent it spiraling irreversibly toward the earth.

They've been missed, between them, on 10 family Christmases and Thanksgivings, 10 Mother's and Father's days. They will be missed again Friday — their shared birthday. Workman would have turned 38; Day, 34.

"I want people to understand: For Gold Star families, they're our sons first," said Keno Day. "This isn't just about a soldier or a sailor."

—

'Kind of immortal' • Workman was 6 when his father's career in uranium milling brought the family from Uravan, Colo., to Blanding.

The youngest of four boys, he was already as tall as the next-youngest, Corey, and a square match for his older brother in backyard boxing bouts.

Workman's grandfather was one of Maj. Gen. Merritt Edson's elite Marine Raiders, who operated behind enemy lines in the Pacific theater during World War II, and Workman struck his mother as genetically coded to be courageous, resilient and driven.

When he returned from Scout camp with a broken hand, she called the scoutmaster, irate. Why hadn't he been sent home sooner?

"Well," the scoutmaster told her, "we tried, but he wouldn't come."

Workman later walked away after his four-wheeler reared back and rolled down a hill, tumbling with him into a pile of rocks, and when he wrecked his father's truck. To Betty, he seemed "kind of immortal."

He became an accomplished athlete — first-team all-state in football and baseball at San Juan High — but never let his successes inflate his ego, said football coach Monty Lee.

On one Friday night in Kanab, after Workman suffered a concussion and wasn't sure where he was or what had happened, teammates convinced him that his girlfriend had dumped him, making him cry.

It was a particularly cruel joke, Lee said, but "when it was all over, he laughed about it as hard as the rest of us."

Workman had resolved to serve a Mormon mission and join the military at an early age, Betty said, following in the footsteps of oldest brother and West Point graduate Timothy.

The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, which came as he neared his degree in criminal justice at Southern Utah University, firmed his plans. He called his mom to tell her he was going to become a Navy SEAL.

Workman endured and passed Basic Underwater Demolition training, the brutal half-year course that weeds out the vast majority of SEAL wannabes, though its rigors deprived him of the nails on his fingers and toes.

Later, in September 2008, he was handpicked for an even more select team of fighters: the Naval Special Warfare Development Group. Called DEVGRU for short, it is widely known by the name of the unit it succeeded: SEAL Team Six.

Workman told his parents to carefully guard that information — "We don't exist," he'd said. He became upset when a DEVGRU team was outed in the May 2011 killing of Osama bin Laden, and he'd had to take an alternate route to avoid the reporters gathered at the entrance of the Virginia Beach base.

The Navy still discloses little about DEVGRU's activities, but Workman's Bronze Star citation for four months of combat in 2010 summarizes his role in a nighttime raid on a "heavily armed foreign fighter commander" that April.

Workman first spotted and engaged an enemy fighter climbing a wall to attack his group. Then, as his group was fired upon from inside the commander's building, he detonated explosives to blast through a wall and used grenades to "neutralize" the barricaded gunmen and complete the mission.

San Juan law enforcement officers saw firsthand Workman's competence and smooth, fluid movements when Corey — who policed for both San Juan County and Blanding — arranged for his brother to train them on active-shooter situations.

And they saw that, in some ways, he was unchanged from the wide-smiling prep standout whom secretary Cathy Cosby remembers grabbing handfuls from her candy basket or writing goofy puns on the checkout roll.

That day, as Workman directed rifle-toting officers into unseen corners at a San Juan High classroom, he saw his old coach, Lee, sitting behind his desk.

Workman stopped, walked over, and wrapped Lee in his big, tattooed arms, before going back to the task at hand.

—

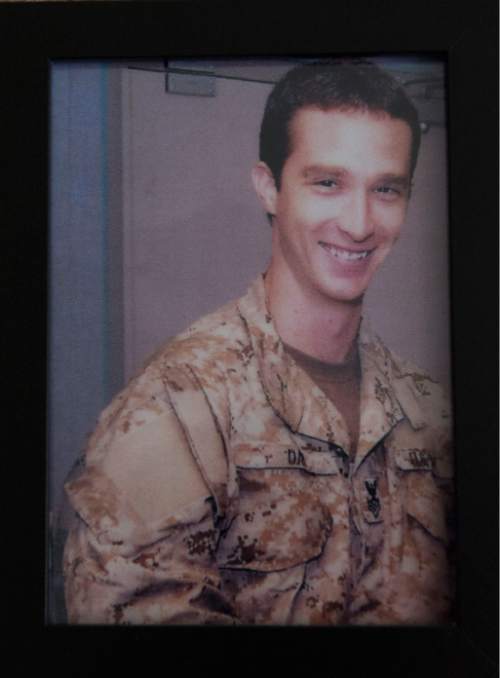

'Not messing this up' • Day wasn't a jock. He didn't have, like Workman, a chin that looked like it could crack coconuts. He wasn't, for that matter, a Navy SEAL, though former teammates tell his parents they remember him as one.

Day was an information systems technician, or an IT, who carried a satellite radio to communicate with command while attached, first, to SEAL Team Three, and later to DEVGRU.

Like Workman, though, Day long held an ambition to join the military — Keno Day figures it started around age 6, when family members found themselves constantly stepping on little green Army men.

Shaun Martin, who was four years younger than Day and was baby-sat by Day's mother, remembers that when they played with G.I. Joe action figures, they didn't just bash them together and shout "Bang." Jared would bunker the Cobra on a hillside as the G.I.s talked strategy.

"He's like, 'We're not just going to go in head-on," Martin laughed.

Day and his sister, Marie, watched World War II documentaries when he was in his early teens. He aspired to be a pilot, while best friend and paintball companion, Paul Seal, eyed special forces. They would achieve each other's goals.

"We didn't have a whole lot of friends outside of our group," said Seal, an Air Force captain. "We kind of liked it that way."

Day avoided situations that might jeopardize his standing with recruiters, Keno said. Once, after her homebody son and Seal had surprised her by asking for a ride to a sleepover, he called minutes after she dropped them off. Come back, he said. Somebody had brought beer.

"I am not messing this up, Mom," he'd said.

Day nourished a huge appetite for popular culture: video games, movies, comics and anime. He did a spot-on Jimmy Stewart and was a natural storyteller — if somewhat prone to embellishment, Seal laughed. On Halloween, he would dress as a mannequin and spring to life as kids approached his porch.

Said Martin: "It didn't matter what mood you were in, if you were talking to Jared, he would make you laugh, and it wouldn't just be a quick laugh — you would be dying of laughter."

Still, Day was nervous when he was assigned to DEVGRU in 2007. Many of his teammates drank — a lot, he told his mom. Day, while not a teetotaler, ran upward of a dozen miles each morning and couldn't abide hangovers. But he wanted to fit in with these formidable men, he said.

"So be the DD," advised Mom.

He proved his entertainment value on deployments, Keno said, by toting his enormous collection of movies and games and setting them up on big screens for the SEALs to enjoy.

He rarely talked to his parents about their missions. DEVGRU's job, he told them, was to "test out really cool stuff," and that had made sense, given the "development" title.

"Now, looking back, we can see why he didn't give out too much information," Keno said. "We would have never slept, knowing what he was doing."

As with Workman, little is known about Day's actions beyond what's recorded in a citation — in his case, a Joint Service Commendation.

In early May 2010, while Day and others were fired at with RPGs and small arms after a 3-mile patrol in mountainous terrain, Day fired back while coordinating reinforcements and air support that led to the safe extraction of his group.

—

'How could you not be proud?' • Seal — who learned about Day's death while he, too, was deployed to the Middle East — said Day had felt "a bad feeling" about his final days.

It was unusual for Day to return to Taylorsville before a deployment, when the thought of unfinished preparations made him antsy, but he'd made an exception and spoken more candidly than usual with family.

Marie Day remembers that for the first time, she heard descriptions of combat injuries from the little brother she'd called "Andy Boy" after the mischievous stuffed monkey in Domino's pizza commercials. She'd had to leave the room.

"I finally started to get a clue. He's not on a ship. He's involved in something more."

She spent Aug. 6, 2011, in bed, worrying, until her parents persuaded her to go out with friends.

On a bar TV, a news report about the downed Chinook reduced her to tears again. A stranger asked what was wrong and bought a round of Jared's favorite drink — a blend of cider and Guinness called a snakebite — for the house.

Together, the dozen or so patrons drank to his health. She felt better.

When she got home, though, there were two sailors waiting in her driveway. After flying from Virginia to Salt Lake City, they had driven from her parents' house in Taylorsville to stop her from driving back on her own, grief-stricken and exhausted.

Often, Keno Day said, she's thought for a moment that it has all been a nightmare.

"He was the light in our family. He really was. He was the clown. When things were bad, he made them good."

Workman made his mother promise — threatening to haunt her from the grave if she broke it — that she wouldn't assign blame if something were to happen to him.

"I choose to do what I do," he told her. "I do it because I love it."

Still, she said, she and her husband cry most days. For Corey, who as a kid watched "Harley-Davidson and the Marlboro Man" with Jason until they knew every line, and who spoke to his brother daily after he enlisted, just about anything can trigger a memory.

"But it's a good thing," he said. "It's not a sad thing. It doesn't depress me. It makes me happy. Anybody would be thrilled to do what he did in his short life."

The Days have surrounded themselves with reminders of Jared.

The first thing a visitor sees upon entering their house is a wall they've turned into a memorial, with photos of their smiling son, medals and plaques, and knickknacks like a Ninja Turtle in sailor garb that hint at his colorful personality.

They make a date of movies he would have been excited to see: "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles," "Warcraft," or anything Marvel-related.

"It's healing," Keno Day said. "We're so proud of him. How could you not be proud of him, for what he did, and what he accomplished?"

In 2013, the ceremony room at Salt Lake City's Military Entrance Processing Station — where incoming service personnel from across the Intermountain West take the Oath of Enlistment — was named for Day.

Workman's name now graces a sign on a bridge spanning the San Juan River in Mexican Hat after the family enlisted state Sen. David Hinkins to sponsor legislation at this year's session. It's among the first places in Utah that Workman took his newlywed wife and later his newborn son, Hinkins told the Senate while reading from a bill written by Workman's sister-in-law, Eva.

"It's not a big, huge bridge like some of the [Chinook victims] have, but it's perfect for our son, because he grew up in this area, and he loved it here," Betty Workman said. "A small bridge for a small-town boy."

Keno and Betty talk sometimes, either on the phone or through Facebook, and former SEAL teammates text or call them on holidays, birthdays and the anniversary of their deaths. Both mothers praise the Navy and associated foundations for making them feel that their sons' sacrifices are not, and never will be, forgotten.

The 30 American servicemen killed Aug. 6, 2011, represent the largest single day's loss of U.S. personnel during Operation Enduring Freedom and in the nearly 30-year history of the U.S. Special Operations Command.

Twitter: @matthew_piper

— Tribune reporter Nate Carlisle contributed to this story