This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When an all-black infantry unit came to Utah in 1896, state leaders sent a formal complaint to the War Department, insisting the soldiers were not welcome.

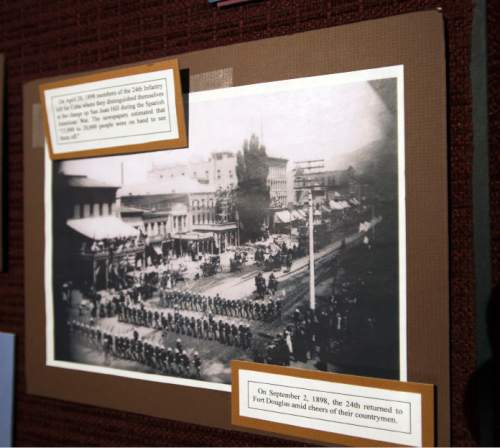

Two years later, after the 24th Infantry battalion returned from fighting in the Spanish-American War in Cuba, a parade in downtown Salt Lake City saluted the soldiers.

It remained a time of racial divides and deep prejudices, but familiarity with the soldiers led to their acceptance.

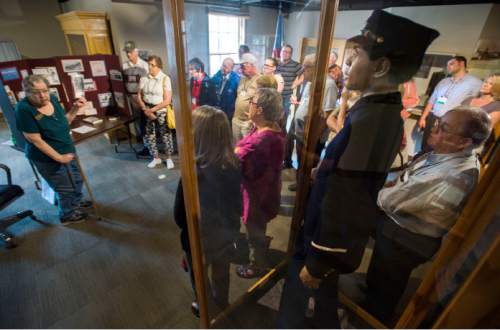

According to Sue Richards, archivist at the Fort Douglas Military Museum, the troops thrived under the spiritual guidance of Col. Allen Allensworth, one of the few African-American officers in the U.S. Army at the time and the unit's chaplain.

"He insisted they all get an education," she said, "[and] that they maintain good hygiene."

Bob Voyles, the museum's director, said when the Utah leaders first griped about 850 male soldiers coming into the area, they feared for their daughters. But after the unit had stayed for a few years, they believed their daughters were safer in the presence of black soldiers than in the presence of white ones.

Thursday's tutorial about the first black soldiers in Utah was part of a daylong tour of the Beehive State's African-American heritage for members of the Mormon History Association, which is holding its annual conference at Snowbird.

After the stop at the military museum, the group visited the Fort Douglas Cemetery, where about 30 African-American soldiers are buried in the west end, populated mostly by those who died during the Indian wars of the 1880s.

At first, the cemetery was segregated, Voyles explained, but it slowly became integrated out of practicality: Spaces were needed for the growing number of military members.

Darius Gray, a tour leader and a noted LDS writer, discussed the pride he had for an uncle who was a Buffalo Soldier on the frontier. The stories he and his cousins heard inspired a cousin of Gray's to enlist in the Army — on Dec. 6, 1941, the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Gray, who helped found the Genesis Group, a support organization for black Mormons, said he joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1964, when blacks were barred from the faith's all-male priesthood. He considers himself a constant missionary for Mormonism.

The tour shifted to the historic Salt Lake City Cemetery, visiting the grave of Jane Elizabeth Manning James, a free black from Connecticut who joined the LDS Church and lived in the home of Mormon founder Joseph Smith and his wife Emma.

She later trekked to Utah a few months after the arrival of Brigham Young and the first Mormon pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley.

Jerri Harwell, another Genesis Group member, portrayed James at the grave. Dressed in pioneer garb, she spoke of James' life as a black Mormon in those early days and rearing her children here.

The visitors also saw the grave of Elijah Abel, who had been ordained to the LDS priesthood in 1836 when Smith was still alive. Abel came to Utah with the pioneers and died here in 1884.

According to his headstone, his son Enoch was ordained in 1900 and his grandson Elijah Jr. received the priesthood as late as 1935 — despite the ban, in place by that time, on blacks holding the priesthood.

Gray noted, with some sly humor, that Abel's final resting place was just a few yards east of Mormon apostle N. Eldon Tanner's.

"We're taught that at the Second Coming, we are to face east," Gray said. "So when that day comes, Elijah Abel will be called up before Elder Tanner."

The tour took place the day after the 38th anniversary of the LDS Church announcing an end to the priesthood ban on blacks.