This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A Utah researcher is calling on the state to mandate rape kit testing after discovering that much of the forensic evidence collected in sexual assaults since 2010 has not been analyzed.

"It's a public safety issue," said Julie Valentine, a forensic nurse and Brigham Young University professor.

The state crime lab is up for the challenge, saying it has the money and staff to handle an influx of kits. And prosecutors say that better DNA tracking of suspects can only help.

But the scientific analysis, critics contend, is costly and not always relevant to a case.

Under public scrutiny, lawmakers around the country have moved to require such testing and have funded efforts to clear backlogs of thousands of unsubmitted kits. Utah has hired an outside firm to test a pileup of 2,700 kits and is creating a database for victims to track the progress of their cases. Neighboring Colorado has required old kits be examined, joining Illinois, Ohio and Texas.

"We have so many resources now," said Jay Henry, director of the state crime lab, noting a $750,000 boost from the Legislature in 2014. Henry believes with new testing, a West Valley City lab set to open in November and additional staff, his agency can handle all new kits. Henry has begun directing police departments around the state to send every sample to the lab.

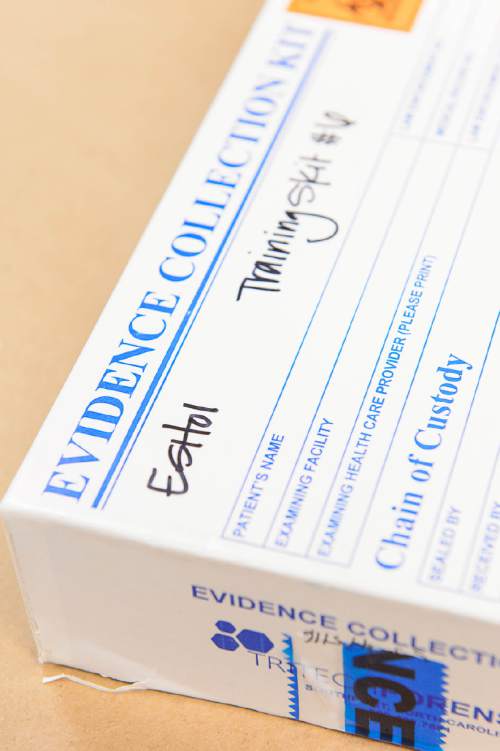

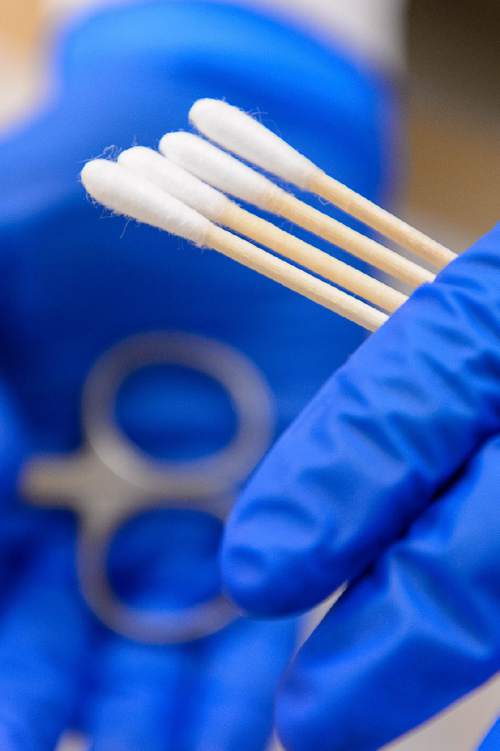

Kits typically cost at least $1,000 and the better part of a year to test. But Henry believes his staff can eventually cut the cost by 30 percent and the wait time down to 30 days with a new system of analyzing only the most pertinent swabs from each kit.

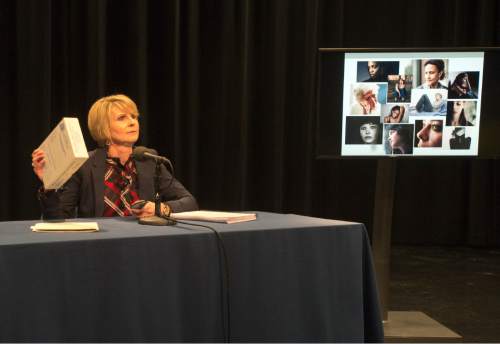

Valentine found that the majority of the 1,870 kits included in her study, collected from around Utah from 2010-2013, still have not been tested. The findings were released in a Thursday news conference at BYU. Police agencies, for their part, said that the state had directed them to send only the most high-priority samples until last year.

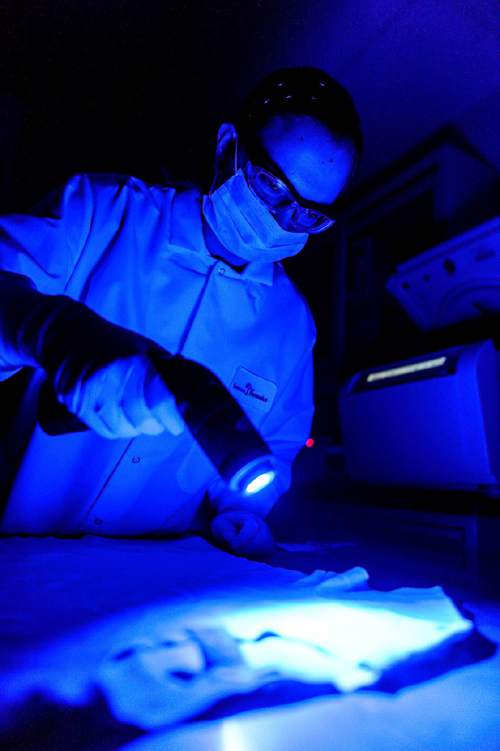

The genetic traces are especially helpful if police still are searching for a suspect, and the analysis can also prove that sexual activity took place.

But if the assailant is not a stranger to the person who reported being assaulted, the kits are less helpful, said defense attorney Susanne Gustin. The same goes for cases in which both parties acknowledge they had sex but disagree on whether it was consensual.

"I think it's a knee-jerk reaction for every single rape test to be tested," she said. "Let's put the resources towards the cases that need them and not towards the cases that don't."

Defense attorney Tara Isaacson agrees. The outcome of a case rarely hinges on DNA, she said, recalling one or two times in her own 20-year criminal law career when it played a part. She believes requiring all kits to be tested may further delay the existing monthslong wait for results.

Of the 400 Utah kits that have been tested from the 2,700 in the statewide backlog, 48 have produced leads in Utah, and three have helped police identify suspects in other states.

Valentine said she initially did not see a need to test all kits, but she has since been persuaded that the testing could detect repeat offenders. Salt Lake District Attorney Sim Gill agrees that testing each kit is a good idea, noting that sharing results with other states could help prosecute more rapes.

"I think there is value," Gill said, to a blanket testing policy.

A mandate also could help police and prosecutors keep biases in check by avoiding the need to pick and choose cases to forward to the lab, he said. They have a duty, he added, to pursue even difficult cases.

Twitter: @anniebknox,

@jm_miller