This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

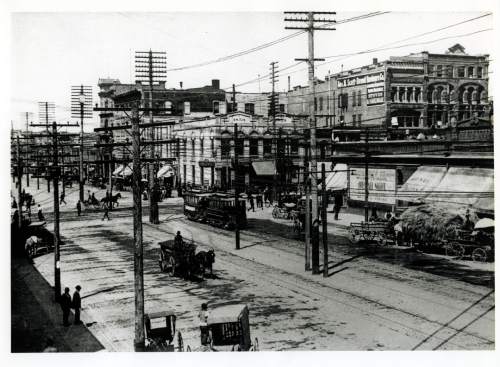

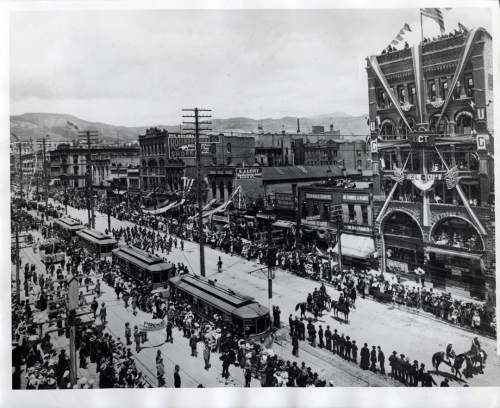

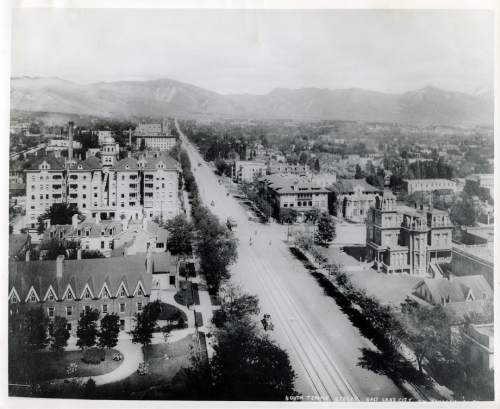

Back in 1914, Salt Lake City streets hummed with electric trolleys traveling on 145 miles of track, carrying 38.9 million passengers — a one-year record that remains intact to this day. It was estimated half the city's residents rode trolleys daily.

A hundred years later, in 2014, the Utah Transit Authority had 46.8 miles of TRAX and streetcar track (a third of 1914 numbers), providing 19.5 million rides (half the 1914 ridership, although the modern population is much larger). U.S. census estimates say 3.5 percent of Salt Lake City-area commuters now use transit (including trains and buses).

The advent of the car and bus killed trolleys by the mid-1940s. A half-century later, concerns about traffic congestion and air pollution resurrected them.

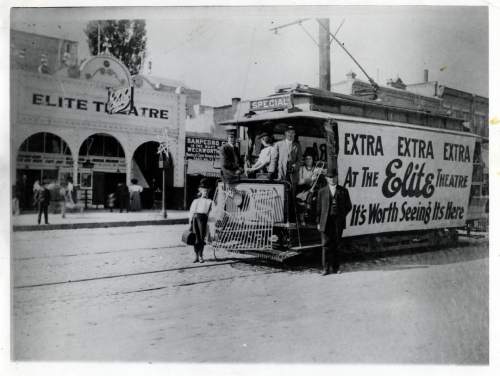

Before they temporarily disappeared, the old trolleys made some fascinating turns through history — including using mule power, having separate trolley companies compete for riders on parallel lines sometimes a block apart, and seeing service stretch up area canyons (which some transit advocates want again).

—

Mules • The first trolley appeared in Salt Lake City on July 17, 1872, built by the Salt Lake Street Rail Co., which was formed by prominent Mormons including two sons of Brigham Young who were LDS apostles: John W. Young and Brigham Young Jr.

Two mules pulled a car on tracks from 300 West at South Temple to 300 South at State Street. A ride cost an expensive 10 cents and was slow — but novel.

Historian Michael Lane wrote that a popular saying in the city then was, "If I have the time, I'll take the streetcar; if not, I'll walk." Still, newspapers reported that 400 to 500 people were riding the line daily.

Service expanded quickly, including a first extension in 1873 to Warm Springs at 200 West and 800 North. Soon the mule cars would reach all parts of the city. Fares eventually dropped to 5 cents and later went for even less with the purchase of books of tickets.

But some problems came with the mules.

Sometimes they would refuse to move. Other times they would run away. A Salt Lake Tribune story on Nov. 18, 1873, told how two mules, named Sin and Misery, were frightened and dashed down South Temple, scattering bystanders as passengers jumped clear. When the driver and conductor finally abandoned ship, the mules simply stopped.

Another time, two mules were entangled in reins and struggled to get loose as they crossed a canal, fell off the bridge and were left hanging in the air. The car did not derail. But as panic-stricken passengers looked on, the conductor cut the mules loose and let them fall.

Mules also caused a pollution problem. J. Michael Hunter wrote in a history of Utah trolleys that Salt Lake City's mules and other horses annually created 60 tons of manure and 3,000 gallons of urine, requiring regular street cleaning.

Also, the early mule trolley cars would often run off uneven tracks, and riders would have to help push them back on.

The line experimented with other power sources, using a streetcar driven by a small on-board steam generator on the Warm Springs line in 1874. But mules were still used until 1889, when conversion to electricity began.

—

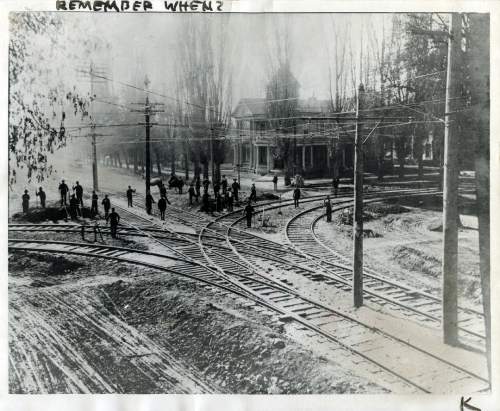

Contention • Competition soon grew. With the advent of electricity and liberal licensing by the city, at least four lines would fight for riders, sometimes on nearby streets along parallel routes.

Historian John McCormick wrote that employees of the Salt Lake Rapid Transit Co. once were busy laying down tracks on West Temple while a crew from the rival Salt Lake Railway Co. went behind them at a safe distance, tearing up the just-laid tracks. Such incidents sometimes led to fistfights.

The various companies eventually consolidated in 1901. The lines then stretched as far south as Sandy and up City Creek Canyon.

Emigration Canyon even had a summer-season railroad. It was built and electrified in 1907, primarily to haul building stone from quarries. The railroad soon figured it could make extra money hauling passengers to the top and built a lodge at Pinecrest. It crossed the creek 16 times and had some steep 8 percent grades.

When concrete replaced stone as the major material for foundations, the Emigration Canyon railroad lost its freight business — and didn't have enough passengers to survive.

Major upgrades to trolleys came in 1906, when E.H. Harriman, the owner of Union Pacific Railroad, bought the majority interest in the consolidated company — and vowed to make it a state-of-the-art electrified train system. He added steel streetcars and 80 miles of track.

He even built new mission-style garages that filled a city block, which today is the Trolley Square shopping mall.

—

Problems • Still, early electric trolleys presented numerous problems.

The early cars had no heat in winter, and straw was scattered on the floors to offer some insulation to prevent frostbite.

Trolleys often were stopped by any obstruction in their way, usually resolved by passengers helping the two-man crew rock the cars back and forth over a bump or irregularity in the track.

The overhead wires sometimes broke in extreme temperatures. At least one motorman was electrocuted when the overhead wire snapped, according to a history of trolleys by Douglas F. Bennett and James W. Woolley.

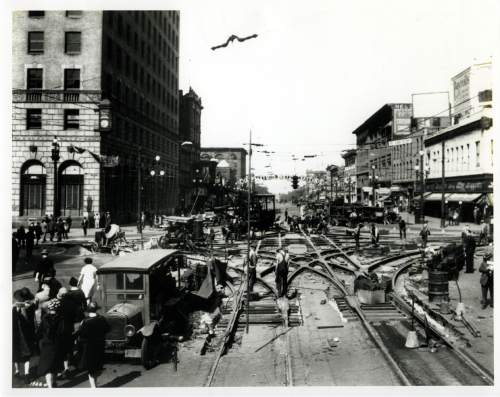

Hunter, author of the Utah trolley history, wrote that congestion also became a problem with downtown streets covered with tracks and overhead power lines.

He said newspaper editorials griped about the mix of trains and automobiles side by side, and they complained that the trolleys actually were the invaders. Editorials called for removal of rails, and vandals greased tracks and stole the electric arms from trolleys.

—

End of line • What truly killed the trolleys was the advent of the automobile and buses. As more cars were sold, trolley ridership dropped. Buses began to replace some trolleys in the 1920s.

Salt Lake City didn't give up its trolleys without a fight. Hunter wrote that the Salt Lake Traction Co. developed a new a type of motor with a lower starting torque that permitted using air-filled tires on trolleys — allowing electric trolleys to run on streets instead of rails.

It attracted business before it was actually able to produce such vehicles by doctoring a photo purporting to show such a trolley running in front of the LDS Church's Salt Lake Temple.

Those rubber-wheel electric trolleys started running on Salt Lake City streets in 1928. But they were still constrained to where overhead electric wires were available, and over time they could not compete with gasoline-powered buses that could go virtually anywhere.

On May 31, 1941, a Deseret News headline advertised that the last trolley would make its final run that night. But Hunter wrote that one trolley line continued operating until 1946, from 900 South and 1300 East to the University of Utah.

Tracks in Salt Lake County streets were torn up and repaved, ending the era of trolley and electric trains — until TRAX would open its first line in 1999.