This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

When Joseph Silverstein stepped off the Utah Symphony conductor's podium at the end of a 15-year run, The Salt Lake Tribune called the man a true maestro.

"Maestro is a word that has been cheapened by popular culture, but among the artists who perform classical music, it is an honorific bestowed only rarely and out of profound respect," the 1998 editorial reads. "In the history of the Utah Symphony, two men have been worthy of that title. One was the late Maurice Abravanel, the other is Joseph Silverstein."

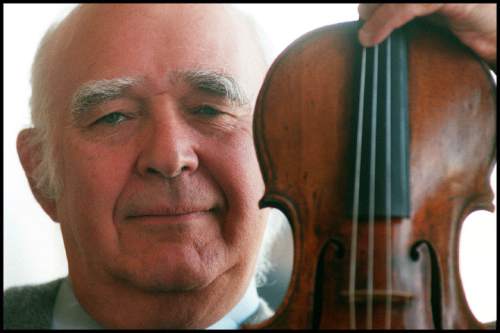

Silverstein, one of the world's most revered violinists and former music director of the Utah Symphony, died Sunday after a heart attack. He was 83.

"Above and beyond being just an incredible musician and perhaps the greatest concertmaster ever, he was a very, very humane person," said Gerald Elias, who knew Silverstein for more than 40 years. The maestro was his violin teacher at Yale University, his colleague at both the Boston Symphony and Utah Symphony, and his dear friend.

The man, by the accounts of his friends, was a massive intellect, an extraordinary musician and a generous soul.

But in 1930s Detroit, Silverstein was just a boy with a fateful birthday (March 21, the same as J.S. Bach) and an uncanny ear for pitch. As one story goes, when Silverstein was 3, he heard a spoon fall to the floor of his mother's kitchen and called out "B-flat!"

(He also shared a birthday with Arthur Grumiaux, another world-renowned violinist, and owned one of the legend's instruments.)

Learning music from his musician father, Silverstein's dream was to join the Boston Symphony. When he misbehaved, his mother would warn him that he wouldn't make it to the famous orchestra, said Noemi Mattis, a longtime friend.

At the age of 23, Silverstein's dream came true. Despite never finishing high school (though he went on to earn several honorary doctorates), Silverstein joined the Boston Symphony, and ascended from last chair in the second violin section to concertmaster in 1962, then assistant conductor in 1971. During his tenure, he became one of the most famous concertmasters of the 20th century.

"He was someone who made the making of music on the violin a guilty pleasure," said Ralph Matson, the Utah Symphony's concertmaster, who also knew Silverstein since Yale. "For him to find an hour with a violin and nothing to do but practice was the equivalent of finding half a beautiful cake in the kitchen and you just couldn't treat yourself to it. It was that kind of delight in music-making. It was quite contagious."

When Silverstein came to Utah in 1983 to lead its symphony, he found an orchestra dispirited by the troubled leadership of the last conductor. But Silverstein took the helm and restored professional respect for the man on the podium.

"The music was never about himself, as it is with many conductors and violinists," Elias said. It's almost impossible for a great conductor not to have a big ego; that's part of what makes them great, Elias noted. But with Silverstein, "it was always about the music. In that regard, he was very humble. … He always took a backseat to the composer. That was always his primary concern. That really was communicated to the musicians."

As conductor, he refined the orchestra's string sound virtually from the time he stepped on the podium. As interpreter, his insights into the German classics — Haydn and Mozart in particular — were high points, and he broadened the orchestra's repertoire as well as its season, according to the 1998 Tribune editorial.

"The lure of playing with him and trying to transcend yourself was too tempting," said Barbara Scowcroft, a member of his orchestra. "He was a magnet. You couldn't resist."

As a world-class violin soloist, Silverstein thrilled Utahns in a second role, and his meticulously shaped performances of concertos and chamber music are treasured memories for audiences. The crown on his achievements as a violinist was his extraordinary tone, Matson said. "He was able to color things with just a sheen of beauty that was remarkable."

His memory for music was astonishing, too. Eugene Watanabe, co-founder of the Gifted Music School, began his violin lessons with Silverstein when he was 13. In the maestro's home on Salt Lake's east bench, Watanabe heard him play almost the entire violin repertoire without sheet music. He was like a computer, Watanabe recalled.

"He would downplay that quite a bit," Matson added. But it was quite remarkable. "In lessons or chamber music coachings, the amount of music that he had at his fingerprints was astounding. I've never encountered anything like it."

Watanabe was just one of countless young musicians Silverstein counseled and encouraged. He supported Scowcroft when she conducted the Utah Youth Orchestra, at a time when not everyone liked the idea of a woman on the podium. He even came to the youth orchestra's practices at the crack of dawn on Saturdays, a giant cup of coffee in hand, after conducting the night before.

To Scowcroft, Silverstein was more than just an inspiration and her conductor at the Utah Symphony. He and his wife, Adrienne, were second parents. They came to Thanksgiving dinner. They helped her through rough times. When her parents died, the Silversteins were there for her.

"He and Adrienne were an extraordinary couple," Mattis said. They had known one another since they were in high school, married at 22, and "were attached at the hip. … They have such a harmonious relationship. They were so much in love and dedicated to their family, their children, their grandchildren and to the welfare of the musicians."

He dedicated himself to many benefit concerts for musical causes. The man was "very considerate and generous with his time," Elias said, "and I'm sure he would like to be referred to as a real mensch."

"He was a real person, too," Scowcroft said. She recalled how, on their way to a dress rehearsal, Silverstein asked to stop at a 7-Eleven, where he bought some red Twizzlers. "Here's this guy who has a photographic memory, his memory is beyond the universe — and he's so human he wants a red Twizzler."

The maestro's 15-year tenure with the Utah Symphony was also remarkable for its length and the artistic continuity he provided. Few conductors spend a decade in one post.

During his leadership, Silverstein used to be an annual fixture on the Nova Chamber Music Series,and occasionally played his violin at Utah Jazz games and other public events.

Even after Silverstein retired in 1998, he found little time to play tennis and golf or visit art museums. He continued to appear as a laureate conductor, performing on a limited basis. He also kept busy teaching and playing concertos, recitals and chamber music. He conducted orchestras all over the world, and was even an artistic adviser to orchestras nationwide.

At age 70, Silverstein continued to be lauded for his performances as enthusiastically as ever. "The very model of musicianship," The New York Times proclaimed.

By Watanabe's measure, Silverstein ranks among the most remarkable violinists in history.

Matson added that "it's remarkable to find someone with that kind of physical gift for the instrument, that raw talent, combined with an extraordinary intellect. It made for a remarkable combination and he was the consummate musician."

In 2002, the symphony threw him a 70th birthday bash at Abravanel Hall, complete with cake and a musical performance from the virtuoso. His performance of the bittersweet Prokofiev concerto was eloquent and incisive. Playing the Brahms on his violin, his controlled intensity and purity of tone made that concerto even more exciting.

The audience, which had given Silverstein a standing ovation before he played a note, responded with hearty applause.

The choices in music were no accident. Silverstein performed the Prokofiev concerto at his Carnegie Hall debut with the Boston Symphony. And Silverstein's 1959 performance of the Brahms won him the silver medal in the Queen Elisabeth of Belgium competition.

"They were both fairly significant moments in my life," Silverstein said in 2002.

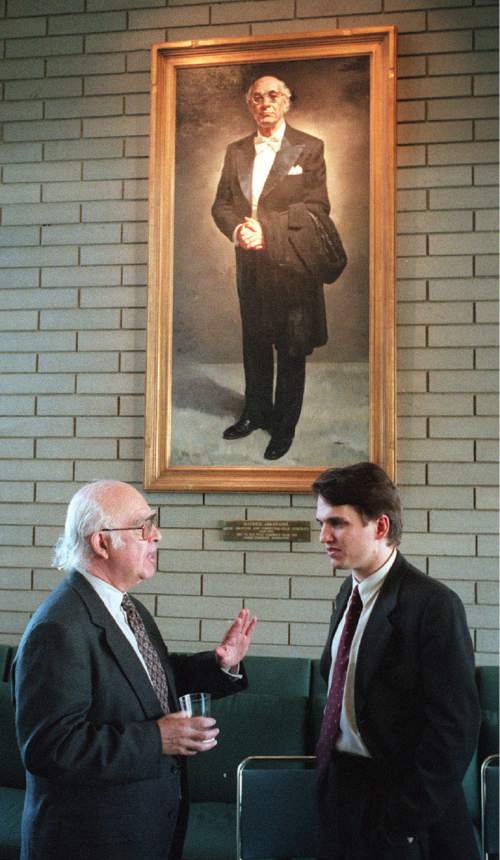

Current Utah Symphony music director Thierry Fischer had a limited acquaintance with Silverstein, who last performed in Salt Lake City in 2008 — more than a year before Fischer was hired here. But at brunch with the elder maestro in New York City about three years ago, "I had a feeling I was in front of someone who played a really big role in the American music scene … a true gentleman and artist of the highest caliber," he said Sunday. Fischer still reflects on Silverstein's legacy when walking past his portrait backstage at Abravanel Hall. "He's a legendary person who we will always remember as a very important part of the story of our orchestra."

Elias, considering what he would want people to remember about his former teacher, colleague, and friend, said that "the Salt Lake community was blessed to have someone of that caliber musician be director of the Utah Symphony."

He is survived by his wife, three children and four grandchildren.

Reporter Catherine Reese Newton contributed to this story.

Twitter: @MikeyPanda