This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note: In this regular series, The Tribune explores the once-favorite places of Utahns, from restaurants to recreation to retail.

The Hotel Utah — closed 28 years ago for conversion into the LDS Church's Joseph Smith Memorial Building — was Salt Lake City's first world-class hotel, an unusual one that would not serve alcohol because of its church ownership in later years.

It wasn't always that way.

It once had a bar, which led the church's president to explain why in an LDS General Conference address (where he also urged members not to imbibe).

And in what may be a surprise for Utahns now, the hotel began its long life as a symbol of Mormon and non-Mormon cooperation — and was initially jointly owned by members of those often-sparring groups.

The hotel's story began in 1909, when civic and church leaders worried about Salt Lake City's lack of a truly fine hotel for important visitors — and believed creating such a building could show that the city was coming of age.

"The Hotel," a book by Leonard Arrington and Heidi Swinton, says several Mormons, Jews, Roman Catholics and Protestants formed a citizens group and decided to ask LDS leaders to allow the construction of such a hotel just to the east of Temple Square.

They proposed using a corner that held the church's tithing office and its Deseret News. The corner previously was home to the church's mint (used when it issued its own coins in pioneer times), and was the first home of the territorial fair.

John S. McCormick, in his book, "The Historic Buildings of Downtown Salt Lake City," said the church approved the use of the site in part to ensure "that as Salt Lake City grew, the area around Temple Square remained a vital part of the downtown area."

The citizens group proposed that the church provide the land and additional funds to own 50 percent of the hotel stock ($500,000), while cooperating businessmen would provide the other half of the initial $1 million in ownership. They proposed raising the other $1 million needed to build the hotel by issuing bonds.

Joseph F. Smith, then the president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, told local newspapers that he was enthusiastic about the project.

Besides the LDS Church, some other early hotel shareholders included prominent non-Mormon banker W.S. McCormick and Daniel C. Jackling — president of the Utah Copper Co. and a principal non-Mormon entrepreneur, who later would live in a suite in the hotel with his family.

Even mining magnate Samuel Newhouse — who then planned and would later build his own hotel on Main Street — bought $5,000 worth of stock to show goodwill.

—

A toast to cooperation • The success of the hotel venture, Arrington and Swinton wrote, inspired similar cooperative efforts.

For example, Rotary International earlier had turned down a request for a club in Utah, believing that Mormons and non-Mormons could not work together. The hotel changed that, and the new Salt Lake Rotary Club was formed in 1912 — and met weekly in the hotel. Rotary held its international convention there in 1919.

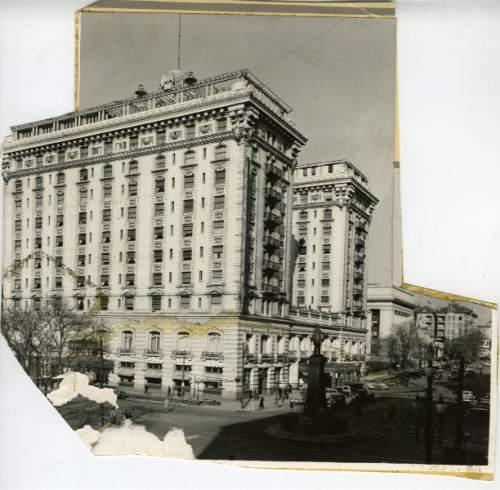

The 10-story hotel opened on June 8, 1911. Hotel Monthly, a national publication, described it as "a noble white palace … centered in a setting of beautiful gardens. No other hotel anywhere in the world has a more interesting or beautiful setting, or more self-contained features for pleasure and comfort."

Joseph F. Smith would say in a General Conference speech that it was "one of the most magnificent hotels that exists on the continent of America, or the old continent either. I am told that it is equal to any in the world."

At first, the hotel included a bar. This surprised many Mormons and prompted Smith to explain why during an October 1911 General Conference speech.

"The people who visit us want something to 'wet up' with once in a while, and unless it is provided for them they will go somewhere else, and instead of beholding and viewing the beauties of Zion they will go where they will see everything that is not beautiful and that which is not good," he said.

Smith added that he wished Salt Lakers would have voted to make the area "dry" — "so that we would not be compelled to allow a saloon or bar to be operated in the Hotel Utah," but the electorate decided otherwise.

He added, "We invite you to keep out of the bar and not go there to drink."

Alcohol would be served in the hotel until Prohibition banned it nationwide.

Over later years, the church bought up almost all of the hotel stock held by others at times when the church was asked to shoulder most of the cost of hotel upgrades and remodeling — and it did not serve alcohol. But it did allow patrons to bring their own to its restaurants, and provided setups.

—

Celebrity central • The luxurious hotel did not take long to attract celebrities. Among the first was U.S. President Howard Taft, who came in October 1911.

The genial 300-pound president was an eager patron of its restaurant. A menu for one breakfast shows he was served cantaloupe, sliced peaches, broiled sirloin steak, bacon and eggs, potatoes mashed in cream, crescents, toast, rolls and coffee. It cost him $2.15.

The presidential suite where he stayed cost $6 a day.

"It is," Taft said, "a hotel that ranks with any in the world."

Every U.S. president from Taft to Ronald Reagan stayed in the hotel before it closed in 1987.

Other notable guests through the years included Denmark's Queen Margrethe II, Norway's Princess Sonja and Chief Justice of the United States Warren Burger; actors Jimmy Stewart, Katherine Hepburn, Henry Fonda, Helen Hayes, Ed Asner, Raymond Burr and Cliff Robertson; and performing artists Van Cliburn, Liberace and Elton John.

But up to the 1960s, some black celebrities had a hard time finding lodging there, or in other Salt Lake City hotels.

Marian Anderson, a famed black concert singer, was allowed to stay at Hotel Utah on the condition that she use the freight elevator, according to "Blacks in Utah History: An Unknown Legacy," by Ronald G. Coleman.

Anderson, of course, is famous in civil rights history for an incident in which the Daughters of the American Revolution barred her from performing in its Constitution Hall. With the aid of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, she instead performed an open-air Easter concert at the Lincoln Memorial before 75,000 people.

Coleman wrote that black actor Harry Belafonte also was refused rooms at Hotel Utah but was accepted at the Hotel Newhouse, which had previously barred blacks.

He said Ella Fitzgerald and her entourage were placed in a black hotel on the west side of Salt Lake City because no white hotel would take them. But Arrington lists her among celebrities who eventually did stay at the Hotel Utah.

The mother-in-law of hotel magnate J. Willard Marriott, Alice Taylor Sheets Smoot (widow of former LDS apostle and U.S. Sen. Reed Smoot), lived in a suite at the hotel for years. Marriott also often stayed there — before his own company built hotels in Salt Lake City.

The Hotel Utah achieved its own minor celebrity status when it was featured in the 1973 film "Harry in Your Pocket," starring James Coburn and Walter Pidgeon.

It was also one of the launching pads for the Osmond family singing group, who as young children often lined up with straw hats and canes in the Lafayette Ballroom to serenade executives and dinner groups.

They once sang "Happy Birthday" in the hotel to LDS President David O. McKay (who lived there in a suite) when some young Osmonds could barely reach his belt buckle.

Guests were expected to dress in coat and tie at the hotel's better restaurants and the decorum was enforced. Famous comedian Will Rogers was once refused service in its Empire Room because he was not properly attired. He borrowed a coat and tie from the front desk, and returned to dine in style.

The hotel was so fancy that it even washed its money during the 1920s. Each day's collection of silver coins was sloshed in a trough filled with buckshot and a chemical solution until they were shiny for use the next day. The hotel also daily exchanged all paper money it collected with banks for crisp new bills.

—

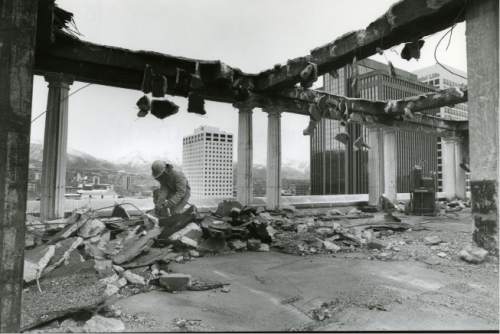

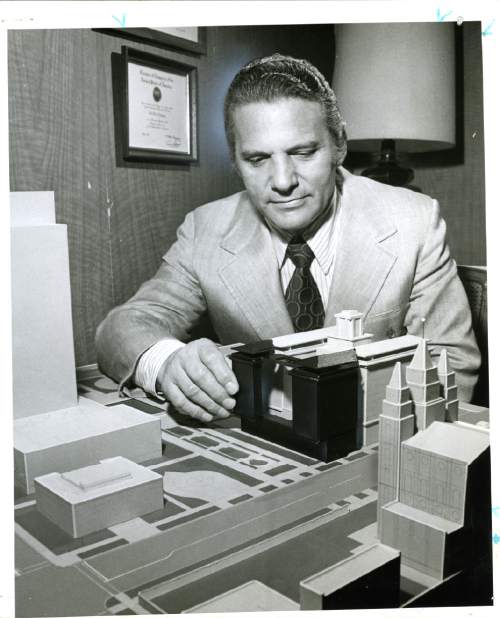

Closing controversy • After the hotel had served for 76 years as an elegant gathering spot for visitors, conventions, honeymoons and parties, the LDS Church announced in 1987 that it would be closed and converted into an office building and visitors center.

The church said the decision "was prompted by the need to either make a substantial investment to update the hotel, in a market now adequately served, or to convert it to other uses." It added that remodeling would provide LDS meetinghouse facilities urgently needed in the downtown area.

The news saddened some civic leaders and historic preservation groups, which tried for a time to sway the church to change its plans.

"I feel terrible," then-Mayor Palmer DePaulis told The New York Times. "Not only are we losing our flagship hotel, we are losing our prestige as a community. That is where it is going to hurt."

After five years of remodeling, the structure reopened in 1993 as the Joseph Smith Memorial Building. It retained its lavish lobby and still offers restaurants — The Roof, The Garden and the Nauvoo Café — plus 13 banquet rooms.

It also houses the Legacy Theater, which shows films about the church, a FamilySearch center and a chapel, along with church administrative offices.

Twitter: @LeeHDavidson

If you have a spot you'd like us to explore, email whateverhappenedto@sltrib.com with ideas.