This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The lengthy era of "midnight annexations" that ate away at the territory and tax base of unincorporated Salt Lake County will come to an end with Tuesday's Community Preservation election.

It's going out in fine electoral fashion, with the County Clerk's Office sending 45 different ballots to groups of voters among the area's 160,000 residents in six townships and 39 unincorporated islands.

Voters will choose a new form of government for their communities. But with that many moving pieces in play, there is likely to be mystery about what the finished product will look like until the votes are all finally counted.

And that won't take place until Nov. 17, when the official election canvass is conducted.

Until then, the biggest question is, "What will Millcreek do?"

With nearly 60,000 people, it's by far the largest of the six townships and has a history of political infighting, with sharp divisions between proponents of city status and advocates for maintaining a sort of status quo by becoming one of the newfangled metro townships.

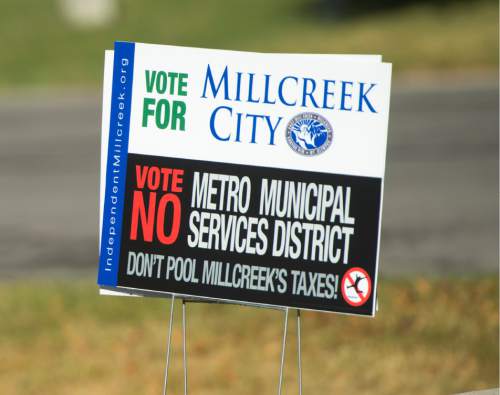

While residents handily rejected the idea of Millcreek City three years ago, incorporation supporters have stepped up their efforts with a well-financed campaign that planted numerous lawn signs and printed glossy newsletters, seeking to sway the vote a second time around.

Will they succeed this time — along with their preference to spurn assimilation with the Greater Salt Lake Municipal Services District? The county set up the district to supply planning and public works services to the unincorporated area in much the same way that police and fire coverage were reassigned to independent agencies.

Or will the opponents prevail once more and take Millcreek into a leading position in the municipal services district by virtue of the weighted vote the township would enjoy on its governing board?

That board will include the county mayor, two members of the council and representatives from each of the other metro townships that opt to join.

Metro township supporter Roger Dudley is confident a "very large silent majority" of Millcreek residents will vote for metro township, having communicated their ideas throughout the community via Protect and Preserve Our Millcreek Township, an email tree organized by a political issues committee.

That organization has raised $8,621 for this campaign but had not spent a dime through Tuesday , according to a filing with the election division of the Utah Lieutenant Governor's Office.

By contrast, the pro-city Millcreek Neighbors for Representative Government had raised $42,280 and spent $35,764 as of that date, its filing said.

These Millcreek City advocates, who include residents Hugh Matheson, Aimee McConkie and Jeff Silvestrini, believe cities are the best form of local government, with a mayor selected in a citywide vote. In a metro township, the council picks a chairperson to represent it in dealings with outside groups.

Most importantly, city advocates argue their community has the tax base required for independence and shouldn't pool its resources with less developed townships.

A fiscal evaluation of the Community Preservation issue by Zions Bank's public finance division suggested that none of the other five townships — Magna, Kearns, Copperton, White City and Emigration Canyon — have the tax bases to support themselves as cities.

They would benefit, the study said, from the economies of scale that would be realized if the townships all banded together and contracted with the municipal services district for services.

While that course of action would seem most logical for these communities, people involved in this groundbreaking process are concerned that mistakes could occur if voters in a community with a tiny tax base opt to become a city simply because they don't know what a metro township is.

Kearns and Magna are on the borderline in this regard, and the communities have residents with diverging perspectives on which option best suits them.

LaDell Bishop, who is a Magna Community Council member, thinks that becoming a city would be good for Magna, as long as it joins the municipal services district, "giving the residents full control over [city] revenues. A metro township will have to rely on the county as we have done in the past."

Similarly, Kearns resident Brett Helsten believes the Community Preservation vote will allow his area "to become a city without having to jump through all the hoops normally associated with being a city," as opposed to becoming part of a metro township concept that is untested in Utah.

By contrast, David Taylor of Kearns and Mick Sudbury of Magna submitted identical answers favoring metro townships to a voter information pamphlet produced by Salt Lake County.

They contended that with the Community Preservation Act essentially protecting the unincorporated areas' boundaries from more tax-grabbing annexations, "a metro township gives voters a chance to test-drive a more formal kind of local government — like putting a toe in the water — without taking the plunge with a full city status."

What will happen with the unincorporated islands farther south in the valley also is difficult to predict.

Some of the islands are as tiny as a single home while others are all or part of a neighborhood. There are also some big blocks of residential development, like islands 13 and 14, which spread from roughly 1150 East to 1700 East on opposite sides of 8600 South.

The county's financial analysis showed that residents of most of these islands would save money if they annexed into Sandy.

But the figures have been contested by Ron Faerber of the Sandy Hills Community Council and David Green of Willow Creek, the latter the largest block among the unincorporated islands.

They maintain that when all the taxes and fees are thrown in, residents will pay more if they annex than if they had stayed in the unincorporated county.

Similar arguments swirl around the Granite community at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon, where there have been ongoing annexation efforts despite strong support for continued county connections from community council leaders.

Since each islands' votes will be counted separately, the election could end up reducing the number of islands from 39 to two or three. But there's no certainty of that, and just as much of a possibility that 10 to 20 could remain.