This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah sixth-graders will have to wait a couple of years to question or analyze evidence that global temperatures have risen over the past century.

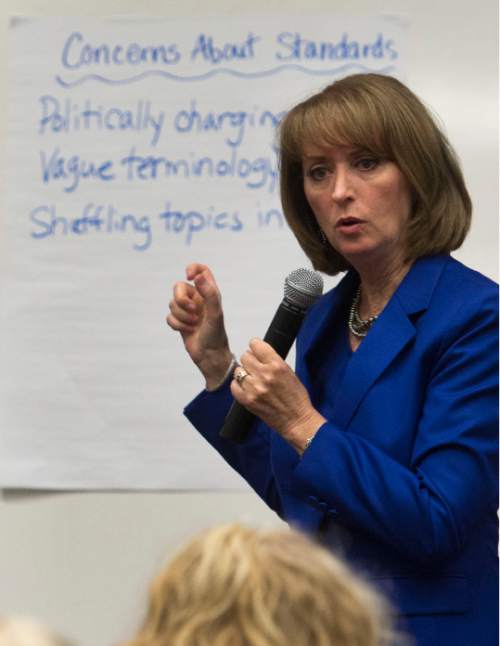

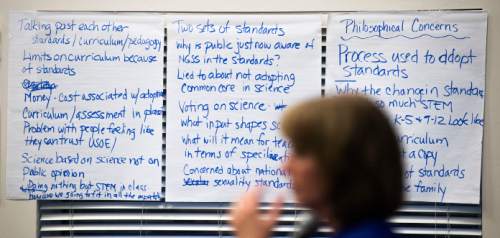

Concerns among state school board members and pushback from parents led to rewrites of a proposed update to science education in the state.

The latest draft of new middle-school-science standards postpones discussion of climate change until the eighth grade, while sixth-grade students learn how the greenhouse effect "maintains Earth's energy balance and a relatively constant temperature."

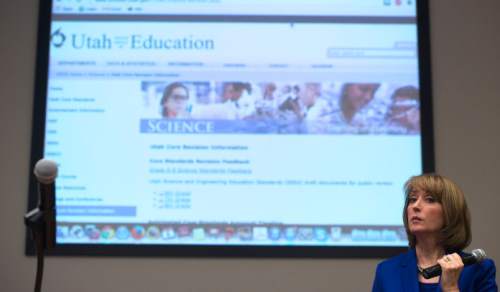

The standards, which outline the topics and skills students should master at each grade level, were released for a 30-day public-review period last week.

If adopted by the board in December, schools will implement the changes in the 2017-2018 school year.

"We were originally hoping for adoption in October," said Ricky Scott, a science specialist with the State Office of Education. "Everything has been pushed back."

And beyond the delay, some worry the school board has given in to political pressure by scrubbing controversial topics from the standards.

Ogden School District science specialist April Mitchell said she was excited by the idea of covering climate change with her sixth-grade students and was disappointed to see the language of rising temperatures had been removed from the latest draft of the standards.

"My concern was that it would create a misconception that our temperature currently is constant," she said. "I think taking that out is withholding evidence from students."

Mitchell works with elementary students of all ages, and she said her classroom includes a question board where children can suggest topics to study.

She said children as young as fourth grade will often post questions to the board dealing with weather and climate change.

"It's something that is in the news," she said. "They hear about it. They see that it's not snowing in the winter."

David Crandall, state board of education chairman, said changes were made based on the content of specific standards, not the politics associated with scientific topics.

"We're not going to make any irrational moves just based on political opinions one way or the other," he said.

Utah's science standards have not received a major update in 20 years, and the latest attempt has been prone to starts and stops.

A procedural school board vote in February faltered, delaying an initial 90-day review period until April while staff retooled the standards for clarity.

Once approved for public review, town hall meetings generated heated debate over the standards, which are largely based on the Next Generation Science Standards, a series of educational benchmarks developed by a consortium of national experts.

That feedback led to the latest rewrite, which was substantial enough to prompt board members to approve an additional month of public feedback and review.

"We are extremely optimistic now," Scott said of the latest proposal.

Scott said the new approach to the greenhouse effect isn't meant to appease climate-change deniers, but instead give incremental information to students.

Setting up the principles of climate and weather patterns in sixth grade, he said, will better prepare students for an examination in eighth grade of the role human activity and carbon emissions play in global temperatures.

"In our current standards, the greenhouse effect is not talked about until ninth-grade Earth science," Scott said. "I don't think politics really came up as much as just making the science strong."

But Mitchell said students don't necessarily need to tiptoe into scientific subjects.

"If they're asking questions about it, then they're old enough to learn about it," she said.

The Next Generation Science Standards do not specify which middle-school grade should tackle a discussion of climate change.

Utah's new proposed standards direct eighth-grade courses to include discussions of changes in global temperatures and regional climate due to agricultural activity, solar radiation, fossil-fuel use and other factors. The standards also include topics in engineering for each grade level, which are presently absent from Utah's middle-school science courses.

"Overall, I think the board was very receptive of the changes that were made," Crandall said.

But the updated eighth-grade standards do not include language about Earth's rising temperatures.

The standards are a minimum expectation, and educators have the ability to provide additional information, Mitchell said, but teachers might feel more comfortable approaching controversial topics if they were supported by the state school board.

"I think you would feel a little more confident in teaching that global temperatures are rising if you were backed by a standard."