This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Late September 2005 was a heady time for the University of Utah's pediatrics department and Primary Children's Hospital. They announced that Salt Lake County would have a role in one of the most ambitious research projects ever undertaken in this country: tracking 100,000 children from womb to adulthood to learn how genetics and environment interact in health and disease.

"Nothing has been done like this to this scale," Ed Clark, chairman of U. pediatrics and chief medical officer at Primary Children's, said then. "It is an extraordinary undertaking."

In December, it all fell apart.

The director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced the agency was pulling the plug on the National Children's Study. A review panel had determined it was too unwieldy to produce good science, let alone sustain it for decades. More than $1.2 billion had been spent, $32 million of it in Utah.

The U. researchers, however, were not unprepared, since the NIH had been backing away for years, even as 40 pilot sites enrolled 5,700 children and planned how to do the main study.

So local researchers immediately turned to Plan B: Carry on with a Utah version of the national study.

The U.'s Institutional Review Board cleared the new study, the Utah Children's Project. Within weeks, researchers began contacting Salt Lake County and Cache County families that had been part of the National Children's Study.

"We will not have as rich or as robust a data set as we would under the National Children's Study," Clark concedes.

Nonetheless, he believed a "stewardship" responsibility for all the time, biological and environmental samples the Utah families had shared — including breast milk, placentas, blood, and dust from air filters and vacuum bags.

"They committed to us as the University of Utah and as Primary Children's," he says. "We went to them and asked, 'Will you trust us with your most intimate data?' "

The families' response has been good, says Joseph Stanford, a professor in family and preventive medicine at the U. and now the principal investigator, Clark's previous role.

The majority of the families that had enrolled children in the national study — 246 children in Salt Lake County and 525 children in Cache County — have agreed to be part of the Utah Children's Project.

And a decade after the national launch, Utah is the only one of the original seven "vanguard" sites to continue the research.

Says Stanford: "It is too valuable to just drop it."

—

A study is born • Anna Reeder cried when the National Children's Study was canceled.

"I was shocked," says the Logan woman, whose first daughter, Cora, 4, was enrolled before she was even born. By the time Mitzi, born in May 2014, came along, the feds were backing away from the study.

"I threw a fit," Reeder recalls. "Why are they canceling this? It could have had worldwide effects."

So she and her husband, Devin Reeder, were happy when the U. contacted them about continuing with a scaled-back study.

The family of four traveled to University Hospital in Salt Lake City, where each underwent a thorough physical, gave blood and urine samples and answered questionnaires. They expect to do the same thing every year until the children are grown.

"It's a whole family project now," she says, "not just the children."

The Utah Children's Project is enrolling the original children and one additional sibling, if he or she wasn't already enrolled, as well as the parents.

The participants aren't reimbursed for their travel or time, but they do get gift cards to restaurants.

For the Reeders and other families, it's not about compensation.

Julie and Sean Benson, who also live in Logan, had enrolled the last of their six children, Mark, now 3, before he was born. The Bensons' eldest son has autism, and they had participated in autism studies that had born fruit, such as learning that autism has a genetic component.

"I thought this was going to be a great thing," Julie Benson says, "helping us to know what's going on with kids."

And Julie Benson figured she had something unusual that researchers might want to study: her age. She was 44 when Mark was born.

Julie, Mark and Katie, 5, who also live in Logan — they were recruited for the original study by Utah State University, which served as a subcontractor for the U. — traveled to Salt Lake City for their exams, questionnaires and biological samples. Sean Benson has yet to schedule his appointment.

"We're hoping it does some good for kids," Julie Benson says.

The end of the National Children's Study was a disappointment for Christine Williams.

"I would think our country would be interested in finding a link," she said, "between what we're doing when we're pregnant or what we're feeding children" and their health.

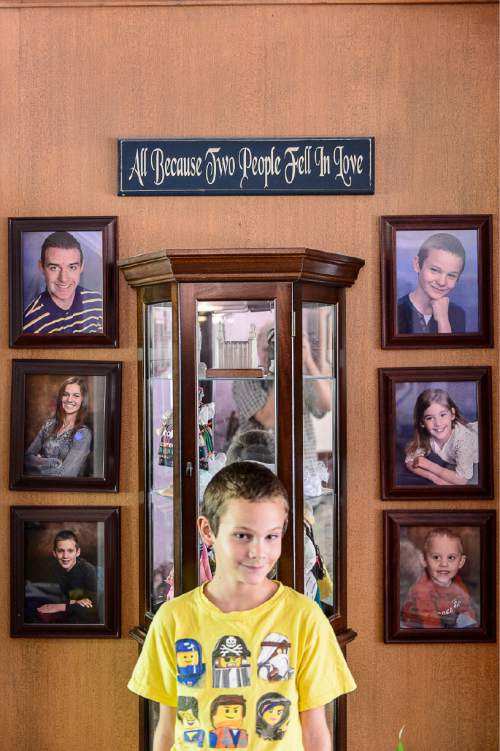

Three of her 14 children — she and her husband, Tom Williams, are expecting a 15th later in the fall — were enrolled in the national study.

U. researchers would come to the hospital within a day of each birth, collecting everything from urine to the umbilical cord, and from pieces of her placenta and the cord blood.

Occasionally, they would visit the Williams home in South Jordan to assess a child's development. They regularly phoned, too, with questions.

Researchers sampled the dirt at their home, and left out a dust collector to assess that aspect of the environment. "It was pretty thorough," Christine Williams says.

Now the couple are enrolled in the Utah Children's Project as well, though one of their children has left the study.

—

Seeking specimens • The Utah Children's Project won't do the extensive home visits or environmental sampling of the National Children's Study — and researchers still are working to get Utahns' specimens back from federal government contractors.

The national project's biological specimens such as blood, breast milk, cord blood, hair, nails, placentas and urine as well as environmental samples like air-filter dust, vacuum bags and tap water are stored in repositories that are not in Utah.

Clark says the U. researchers have copies of the few analyses that were made, but most of the specimens have not yet been scrutinized. Some are frozen, he says, some are "fixed" in stabilizing agents and some are on filter paper.

They want the collection of Utah samples, he adds, "and are applying to get it back."

The NIH has not yet seen a formal proposal for a transfer of specimens. In an email response to a question, the agency wrote that the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development would share samples with researchers "in such a way that they can be used for several efforts, and not used up in any single endeavor."

Utah Children's Project has scraped together, from donations and the pediatrics department, a budget of about $1 million. Where the National Children's Study funding provided for 30 or so employees locally, the revamped endeavor has enough money for the equivalent of three full-time workers.

The project won't have the breadth of data that would have come from following diverse children living in cities and rural areas throughout the country.

"It's the difference," Stanford says, "between 1,000 and 100,000."

But he hopes to collaborate with researchers doing similar children's studies in Europe and Asia.

"It just will be more complicated to make those links," Stanford says.

And if Clark has his way, the project will attract enough grants and donations to expand the net to include more siblings and even grandparents.

"That would be remarkably rich to study," he says. "My vision is this will outlive me, and we will recruit at least two generations."

Looking for answers

Ed Clark, chairman of the University of Utah pediatrics department, says parents of seriously sick children have five main questions:

"Will my child be OK?"

"What caused this?"

"What about my other children and grandchildren?"

"Do you know what this condition has done to me and my family?"

"Are you listening?"

Clark hopes the Utah Children's Project will lead to more answers.