This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

During World War II, the United States and its Allies defeated enemies on two sides of the globe, but the impact on Utah cut across many fronts.

In fact, historians say, the war transformed the Beehive State — economically, socially and otherwise — more than any other event since the Mormons' arrival in 1847.

A relatively isolated place before Pearl Harbor, Utah had become part of mainstream America by the time Japan officially surrendered to the U.S. and its Allies aboard the USS Missouri 70 years ago Wednesday, on Sept. 2, 1945 — V-J Day.

The war effort sent men to foreign countries they otherwise would not have seen. By 1945, more than 62,000 Utahns were on active duty. With their victory, they came home with new ideas about the future — including more skiing in Utah.

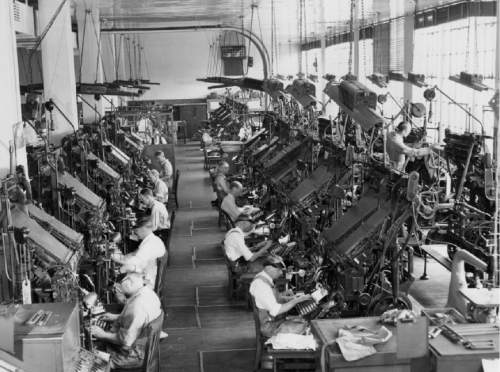

The conflict also tugged women into the workplace by the thousands. In a period of months, their roles shifted dramatically. They were hardworking, not afraid to get dirty and key cogs in the economy. Women earned a new kind of respect.

Meanwhile, transported soldiers and airmen from every corner the country arrived at various military bases in Utah, where they mingled with the female civilian population, providing new accents and insights into other American cultures.

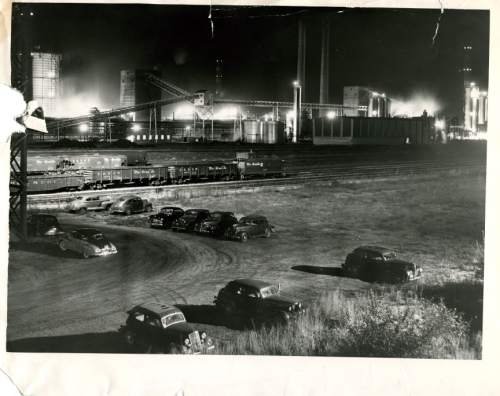

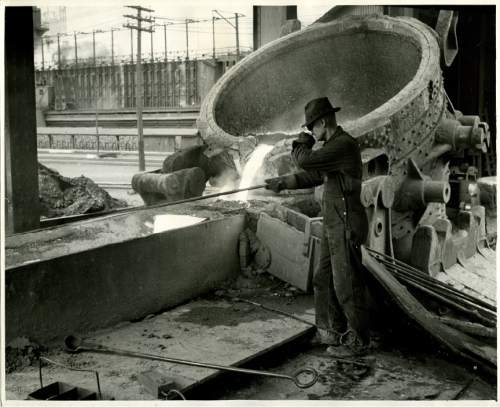

The conflict reshaped Utah from one of the Depression's hardest-hit states to one of unlimited jobs in booming industries and surging military installations. News photos of skinny men with shovels in the Civilian Conservation Corps building dams in the canyons were replaced by images of men and women assembling aircraft in giant hangars or rolling out steel by the ton.

It marked a sea change from the 1930s, when Utah's unemployment rate hovered around 33 percent. As the nation geared up for battle, 14 military installations in Utah employed 40,000 civilians. Remington Arms had some 10,000 workers. And Geneva Steel — built in Utah because military leaders believed it too distant to be targeted by Japanese bombers — tallied a workforce of 4,200.

Workers could log as many hours as they could stand, explained Brian Q. Cannon, a history professor at Brigham Young University and the director of the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies.

"It was simply revolutionary. There were very few facts of life that weren't impacted," Cannon said. "Nothing has altered the landscape here at home as much as the Second World War."

More than 412,000 Americans perished in the fighting — more than 3,000 of them Utahns. Many who made it back suffered from "shell shock" — what is now known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

"The war had a tremendous impact on families," Cannon said. "Spouses [of servicemen] were affected by the war, as well."

The conflict demanded a lot from Utahns and all Americans — on the battle lines and the home front.

"The attitude of sacrifice was forced upon the citizenry," said Robert Voyles, a retired colonel who now directs the Fort Douglas Military Museum. "There was this notion of pulling together. The country pulled together like at no other time."

—

Women at work • Most men of fighting age were shipped out to battlefields in Europe, North Africa or the Pacific, leaving women to labor in defense installations, toil in agriculture and work in stores and offices of all kinds. It was a big switch for most Utah women, who were homemakers or on track to marry men and rear families.

"The impact for women — even married women whose husbands were off fighting — was that they developed self-sufficiency," said Allan Kent Powell, former senior historian for the Utah Historical Society and author of the 1991 book "Utah Remembers World War II."

The pace of romance also shifted.

"During the Depression, people postponed marriage and families," Powell said. "But during the war, it was, 'Let's get married. We don't know what the future will bring.' "

More than anything, women sought to make a difference in the war effort, said Kathryn MacKay, a history professor at Weber State University.

"Some of their work was very difficult," she said. "But they did it, and they were proud of it."

Not all women worked for wages, MacKay added. "They were in support of the war effort," she said. "They heard the call and answered it."

Utah women had a different attitude when it came to child care, MacKay noted. They preferred that family members tend their kids, rather than placing them in child care provided by military bases or defense contractors — as was common in other states.

At war's end, some working Utah women were uneasy about losing their jobs to men returning from war.

"But Utah women understood it was time to get on with things," MacKay said. "The larger society said, 'Women, you've done this — now go home and have babies.' "

Even so, women felt freer to enter the workplace.

"It heightened their expectations after the war," Cannon said. "Women had proved they could thrive in any job. And it increased the options of going back to work."

—

Booming bases • Joining the women in factories and defense installations were people — mostly men — from across the country who had migrated to Utah for work. They were white, black, Latino, American Indian. And, of course, soldiers and airmen streamed into Utah for training. In a matter of months, the state had become much more diverse.

Hill Air Force Base blossomed from a minor airfield into a major air base. Fort Douglas underwent a sweeping makeover. Today's township of Kearns, population 36,000, owes its origins to Camp Kearns, which sprouted up as an Army Air Base during the war. West of Salt Lake City, the Defense Department — then called the War Department — created the Tooele Army Depot, Dugway Proving Ground and Wendover Army Air Base, where crews trained for the historic war-ending bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Wendover's air base has long ceased to function, but the retreat near the Nevada border remains a popular destination for gamblers.

During the 1940s, Utah's population mushroomed by 25 percent — from about 550,000 to 688,000.

"A lot of soldiers passed through Utah and some of them came back after the war," author and historian Will Bagley said. "The girls seemed to enjoy it. The USO would welcome the troops. There was music, sex and alcohol."

It's also worth noting the influx of some 11,000 Japanese-Americans who were held in a West Desert internment camp called Topaz. After the war, Cannon noted, about 1,000 of them remained in the state.

Utah retains a large military presence that brings people from across the country and remains a major employer.

Hill Air Force Base, in particular, is an important installation, one that Utah's power brokers consistently lobby to keep operational. Less visible is the West Desert's Dugway Proving Ground, where elite military forces continue to train in relative obscurity and secrecy.

"In some ways, the military-industrial complex came to Utah in World War II," Bagley said, "and never left."

—

Middle march • When the guns fell silent, Washington fought to keep the country from slipping into recession — as it had after World War I — and scouted for ways to reward the sailors, soldiers and airmen who had so bravely defeated enemies on two fronts.

Congress passed the GI Bill, which helped pay for college and other types of training, as well as mortgages for veterans. The legislation led to a building boom and an educated middle class.

"The possibility that people saw coming back from the war was that they could expand their earning capacity and their education," Powell said. "The real significance, in many ways, was the establishment of a [larger] middle class."

After the sacrifices of the Depression and the war, a new day had dawned.

"People were ready to build families and buy homes and cars," Bagley said. "There was this huge demand, and it prompted a second economic boom. America just goes gangbusters after the war."

Between military training and advanced education, a new group of leaders emerged.

"They had the "finest training in American history," Bagley explained, "They came back ready for anything. You had a new generation of business leaders who were ready to tackle the world. And they did."