This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note • In this regular series, The Salt Lake Tribune explores the once-favorite places of Utahns, from restaurants to recreation to retail. If you have a spot you'd like us to explore, email whateverhappenedto@sltrib.com with your ideas.

—

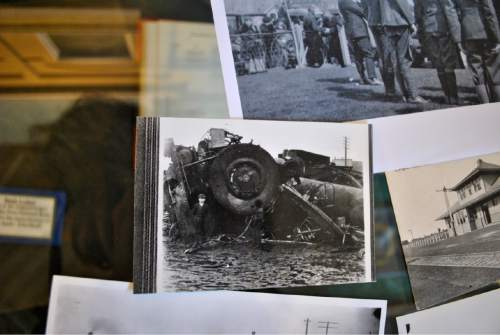

Each generation of Layton residents has a different memory of the building that stands at 200 S. Main St.

Those under age 45 or so remember skipping first period at Layton High School in favor of bigger-than-the-plate scones at Doug & Emmy's.

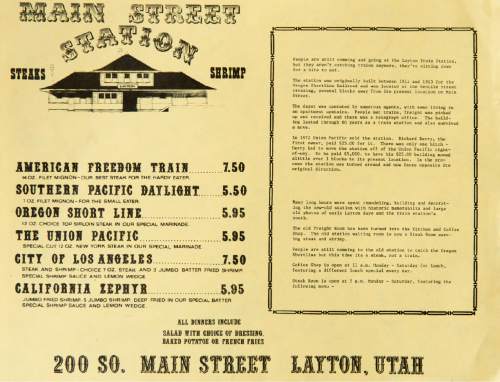

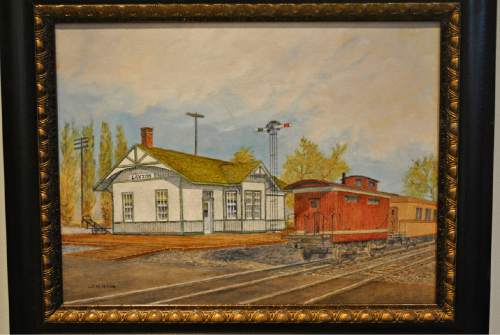

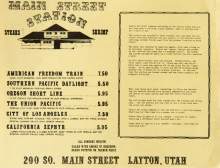

From 1974 to the early '90s, it was Main Street Station, serving hot sandwiches by day and steaks and shrimp for dinner. A 14-ounce filet mignon, "for the hardy eater," cost $7.50.

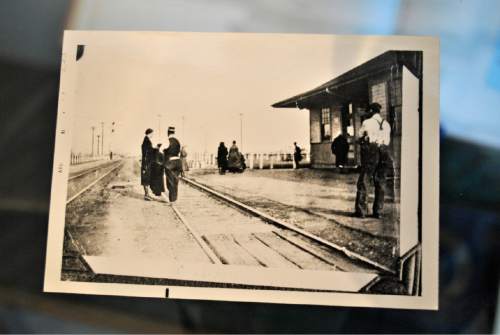

Prior to 1971, it served as the area's train station, where tearful farewells were said to soldiers shipping off to world wars, and to LDS Church missionaries heading for the field.

In the future, people might reminisce about the giant burritos served at Cafe Sabor; by Christmas, the station will be the Mexican restaurant's fifth outpost.

But for the past seven years, the former Layton Depot has been just an increasingly derelict white building, a less-than-welcoming sight for FrontRunner passengers stopping in Layton.

The building was slated for demolition as part of the massive construction project that turned the southern end of Main Street from a southbound Interstate 15 entrance into a bridge interchange. Using eminent domain, the Utah Department of Transportation booted Doug & Emmy's and a handful of other local businesses.

But during a review of the conceptual bridge design plans, it was discovered that the interstate bridge wouldn't work unless Main Street moved slightly to the east. The kind of late realization that's a planner's nightmare, it was more of a miracle for Layton City — moving the street would take the train station out of the bridge's direct path.

"I was like, 'Yes! That'll save the train station!' " recalls Bill Wright, Layton City's director of community and economic development."We were very fortunate. It was very close to being demolished."

Still, it wasn't a coast from there. UDOT donated the building to the city, but rehabbing a structure is more expensive than starting from the ground up, Wright says.

And when you're dealing with public money, sentiment can't outweigh economics. So, over the next few years, the city used block grant funding to renovate the exterior all the while looking for a buyer who would do right by the station's history.

—

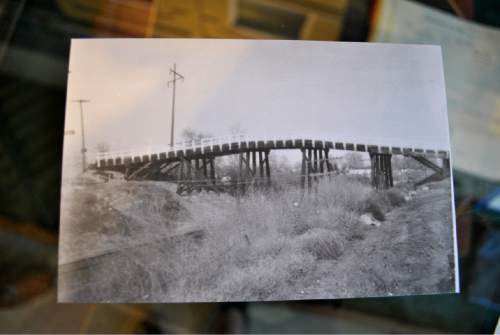

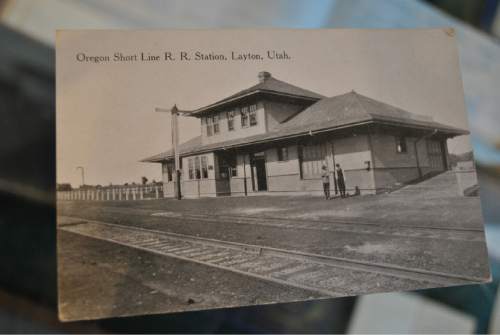

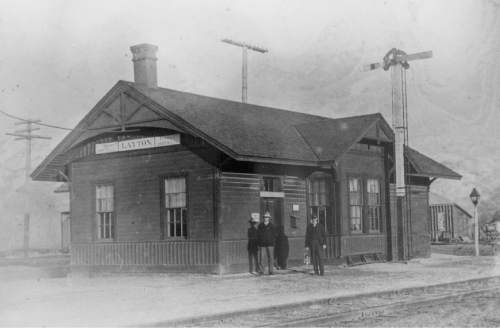

Home cooking • The depot opened in Layton in 1912, just five years after the farming town officially split from Kaysville. A stop on the Oregon Short Line — a subsidiary of Union Pacific — the station connected residents to Morgan, Salt Lake City, Idaho and beyond. During the two world wars, sons bound for military service said goodbye to their families at the depot. Twelve never came back.

In 1971, Union Pacific ceased its passenger service, and the terminal was used just for freight, says Bill Sanders of the Layton Heritage Museum. Union Pacific sold the building in 1972 to the highest bidder, a man named Richard Derry, who paid $25 for the depot on the condition that he move it within 30 days — a feat that ended up costing him $5,000.

Derry relocated the depot a few hundred feet south, still along the railroad line, and also flipped it 180 degrees so its platform faced the street instead of the tracks. But the building was soon sold again and converted into a bar.

Across the street, Sill's Café was in its second decade of serving home-style food to the farmers and families who wanted a good, filling meal without paying a lot for it. But it wasn't the Sill family at the helm — it was Shana and Ted Ellison.

Shana's parents, who'd owned a restaurant in Kanab, heard about the homemade pies at Sill's and went to try them when they moved to the Wasatch Front. Genevieve Sill, who established the restaurant on Main Street with her husband, Golden, got to talking with Shana's mother — and eventually talked her into leasing Sill's so that she could take a break.

The restaurant had a good clientele — plenty of regulars who came for coffee, conversation and scones. Not the hard triangle scones you'd find at an English tea service, but a plate-size slab of deep-friend dough slathered with honey butter. Shana's mother had learned how to make Navajo tacos when they lived in southern Utah, and then taught Shana, who grew up not only cooking but also making cream and butter from scratch.

"I wasn't looking for a job, but I said I'd help my mother," says Shana Ellison, who was living in Kaysville raising her small children at the time. That part-time job turned into a full-time job — and then Shana's mother persuaded her to take over the Sill's lease when she and her husband moved to California.

Food ran in the family — they often gathered at Grandma's house, and "you couldn't walk in the kitchen but she'd give you a task," Shana says. "Start churning this butter, go here and start mixing this bread." But cooking for even a big family is different from making breakfast for an entire town. Shana's mother stayed on to show her a few things, but otherwise, Shana just had to figure it out. "I just started cooking a lot," she says. "If I ran out, I'd do more next time."

Shana ran the restaurant for three years, employing some of the Sill children — including Emmy Sill, later Emmy Criddle of Doug & Emmy's.

When the new generation of Sills was ready to run the restaurant, Shana's lease wasn't renewed — but her customers weren't ready to say goodbye to her cooking. They investigated the recently emptied depot, where the bar and its loud music had failed to take off.

"Some fellow bought it out of bankruptcy court," Shana says, and other customers helped her find or build equipment to open her own restaurant in the former train station.

Arriving at Main Street Station • The Ellisons began renovation in 1974, clearing out the mess left by the former tenants — garbage was piled high, Ted says.

There were also treasures to be found. When they tore out the counter out to replace it with one they bought from a defunct cafe near East High in Salt Lake City, Ted found a telegram, dated 1920, from his grandfather to federal sugar agents in the East, telling them how much sugar was at the Layton Sugar Company — which Ted's family had operated.

They scoured the valley for used restaurant equipment, counters and booths. "We were on a shoestring," he says.

But when they opened Main Street Station, business was good. Layton wasn't the hub of chain restaurants it is today, and there was more than enough appetite for the good food being cooked on Main Street by the two families.

The Ellisons turned the former freight room (used for dancing when the building was a bar) into a kitchen and coffee shop. The waiting room became a steak room: "People are still coming to the old station to catch the Oregon Short Line but this time it's a steak, not a train," notes a menu.

Running the restaurant kept them both busy. Ted claims no cooking skills and says beyond dish-washing, he kept out of Shana's way. During the lunch hour she was a blur, cooking, bringing food to customers, mopping spills — anything that needed to be done. Her daughter, who started working at the restaurant on Day 1, was her second in command, in charge of opening the restaurant each morning and getting lunch started. There was also a team of cooks and waitresses, many of whom Shana still keeps in touch with.

Nothing in the kitchen came from a package. Gravy was made from drippings. The mashed potatoes were just that. Leftover roast beef from Wednesday's sandwiches was chopped up and made into a stroganoff special for Thursday.

Stephanie Assenberg Kline spent most of her summers with her grandparents in Layton. "Whenever Grandma wasn't going to be able to fix lunch — too busy canning, quilting or playing bridge with her friends — Grandpa would take me to the Main Street Station," Kline posted on Facebook. "I just loved it when Grandma couldn't cook!"

But when the customers had left, the hash browns were prepped and the lights went down, the building lost some of its homey feel. There were rumors of ghosts. "It's an all-wood structure, so it creaks and moans," says Ted, who worked in the Davis County Sheriff's Office. He'd "turn the jukebox up and try and make it so it sounded like there were more people there" when he was painting or fixing walls at the restaurant late at night.

Someone told the Ellisons that when one of the depot agents had died, his viewing had been held upstairs. "I find it hard to believe they carried his body up those long stairs," Ted says, "But if that happened .... The place was pretty eerie to be in late at night."

More than ghosts haunted Main Street Station, which was broken into multiple times. The opening-up money — cash for the morning crew to make change with — was stolen even when they hid it in the flour. The second time the thieves broke through a window, the Ellisons just put up cardboard because they knew it would happen again.

One night when Ted and Shana were out to dinner, their plates had just been set in front of them when Ted had a sudden premonition. "We're gonna get hit tonight at the Main Street Station," he recalls thinking. He'd never had such a feeling — "like a ton of bricks" — before, so they got their steaks to go and drove to the restaurant. For 30 minutes, they sat in the darkened restaurant, waiting for something Ted was sure would come. (The suspense eventually got to Shana, who went to wait in the car.) Ted looked out the broken window and saw "white T-shirts coming through the alfalfa." He called for assistance and heard motors start up all over town. The burglars — teens from west Layton — were apprehended that night.

After that, Ted took a proactive approach to security. He visited nearby residents and introduced himself — so when a woman came home one day and found a bag of meat and cheese on the kitchen counter of her trailer, she knew where it had come from and turned it over.

In 1985, Shana was tired of working 20-hour days and sold the restaurant to her daughter. She ran it for a few years, then sold it — and it became Doug & Emmy's.

End of the line • Doug & Emmy's carried on the tradition of serving giant meals to old-timers at the counter, families in large booths and groups of teenagers cutting class in the back room, hoping they wouldn't run into their parents when it came time to pay at the cashier.

"I lived in a humble Layton home, like any other family in our area. There were eight of us; eating out was uncommon," says KayLee Taylor. "Doug and Emmy's was reserved for special occasions: a holiday, after a long day of work, or when someone left on a mission. We'd get two or three scones for take out, and I'd try to stand patiently under their ceiling fan and wait for the white boxes overflowing with scones and honey butter."

For Jason Murphy, one memory stands out — from 1996, his senior year at Layton High School. The football team had made it to the state playoffs, but lost in the quarterfinals. "For most of us," Murphy wrote on Facebook, "that would be the last time we played organized football. Ever."

His parents could sense his despondency and suggested he skip school — but took him to Doug & Emmy's instead of letting him sulk in his room. "We walked in and found that many seniors of the football team had the same idea. Even the coaches were there," Murphy wrote. "It wasn't planned; we all just ended up there."

The atmosphere in the restaurant was less energetic than usual; more somber as the players reflected on the past season. "But after a hearty meal of a plate-size Denver omelet and a blueberry fritter (a scone smothered in glaze frosting), along with camaraderie of my peers who were going through the same thing, I was able to go back to school that day knowing that life was good even if it is bittersweet," Murphy wrote.

But the end of Doug & Emmy's was more bitter than sweet, as construction claimed the south end of Main Street. Owners Emmy Criddle and Doug Madsen tried re-opening the restaurant in Sanpete County, but it didn't succeed.

Scone fans can still find them at Layton breakfast staple Sill's, which shares DNA with Doug & Emmy's. After moving from Main Street, Sill's relocated a few blocks east to the former Pizza Hut on Gentile Street; its scones were named Utah's "Best Breakfast" in 2010 by Food Network Magazine. Various other relations of the Sill/Criddle families operate Criddle's Cafe in Ogden and Granny Annie's in Kaysville and Bountiful.

Preserving memories • When plans began moving forward to rehab the station, Ted Ellison helped with the planning and thought tentatively about opening a restaurant there again. He'd retired in 2007 after 35 years in the sheriff's department and had never lost his habit of collecting railroad memorabilia. But Shana — who after Main Street Station opened a steakhouse near Cherry Hill, then worked at the Fifth Amendment bar in Bountiful for 14 years — didn't want to go back to 20-hour days cooking food for other people. And Ted didn't want to risk his retirement.

So, now they watch the station's progress from the outside — a more comfortable spot than the kitchen of the 2,400-square-foot building.

"Layton has done A-plus job of putting this back together," Ted says. "It's going to be a real asset to Layton City." He just hopes the new owners and tenant respect the building's history as a railroad depot and decorate it to match. The first step, he says, would be painting it a classic color — something other than white.

He might get his wish.

There has been frustration with how long the station has sat empty, but the city wanted to do it right, says Bill Wright. UTA added a parking lot to support a commercial venture in the space. And the city finally found the right owner — Jared Nielsen, who also developed the nearby Kays Crossing apartments. "Preservation has to be part of your blood," and it's part of Nielsen's, Wright says. "There are easier ways to make a dollar, easier ways to build a building."

After sitting vacant for so many years, the station's interior had to be gutted, Nielsen says. And because the station still looked like a vacant building — or people just thought of it that way — its new windows were smashed by people throwing rocks, Wright says. So they've boarded up the windows and have begun leaving a light on at night.

The building will see a fresh coat of paint in the coming weeks — maybe a forest green, Wright says. Nielsen hopes to have all the exterior work done before winter weather hits, and thinks the interior will start to take shape in late October. The city has its application to the historical register prepared and will submit it after the building is completed. And Cafe Sabor — which operates in Logan's historic train station as well — snapped up the lease and plans to be open by Christmas.

The train station will again welcome passengers — this time stepping off of FrontRunner. "That's what preservation is about — the physical, and then the social and memory." If the building had been demolished, he says, those memories — of soldiers, the railroad, football, ghosts and scones — "would've faded for the next generation."

Twitter: @racheltachel