This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Her husband dead. Her 17-year-old son dead. A younger son, who had witnessed the murders, shattered.

Now, accused killer Joe Hill was dead, too, at the hands of a firing squad, and a reporter came knocking.

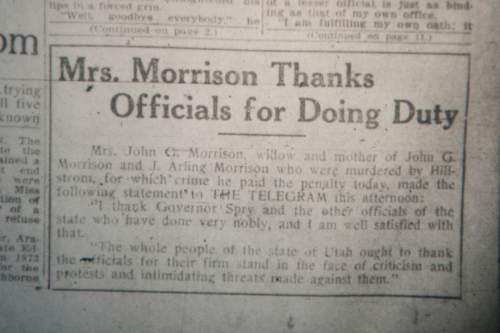

The Salt Lake Telegram in November 1915 quoted widow Marie Morrison saying she was grateful that Utah officials had carried out the death sentence imposed on Hill, the renowned songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World.

Marie's words soon came back to her, clipped out of the newspaper and accompanied by an anonymous threat against her eldest son: "You have signed Perry's death warrant."

For a century, the infamy of Hill's arrest, trial and execution in Utah has endured and grown, fed by legend, books, news reports, commemorative events and song. In the shadows, meanwhile, the loss of John G. and J. Arling Morrison has resonated through five generations.

Marie, terrified, had the windows of her home painted shut.

Her surviving children "were told not to talk to strangers, not to tell anyone their names and to be very careful where they went and who they talked to," said granddaughter Marilyn Morrison-Ryan, 78, of Salt Lake City.

The murders and the aftermath drove Marie to become somewhat of a recluse, "to pull down the shades and try to shut the world out," said grandson John Arling Morrison, 84, of Mesa, Ariz. "It devastated her."

Her daughter and sons struggled — some with alcoholism, all with anger — as they grew up, and their distress shaped their own children.

"Common sense tells me these people went through post-traumatic [stress] syndrome without any counseling or help whatsoever and [were] left with the possible option of more fear to come," said Morrison-Ryan, who fights tears as she imagines the young family's grief. "It had an impact on their personalities."

Now, as concerts and other events are planned to mark the 100th anniversary of Hill's execution, Morrison descendants want John and Arling, and the impact of their murders, to be remembered and recognized.

The Morrison grandchildren have few doubts about Hill's guilt. But their family's story has been eclipsed by persistent skepticism — a debate heightened by a recent book that proposes a violent criminal as the more likely murderer.

And that raises this question: Could a century of bitterness at the tributes for Hill, which has intensified the pain of losing John and Arling, have been needless?

If Hill was executed for a crime he did not commit, Ryan-Morrison said, "I would cry. It would just tear me apart."

—

'We've got you now!' • On Jan. 10, 1914, John Morrison and two of his sons were closing the family's grocery store in a small brick building at 778 S. West Temple.

It was a cold Saturday night and John was tugging a bag of potatoes near the front door. Arling, 17, was behind the counter on the other side of the center aisle of the store. Merlin, 13, was in a doorway in the back.

Two men burst in, with red handkerchiefs covering their noses and mouths.

"We've got you now!" one gunman yelled and fired on John, who collapsed, mortally wounded.

Arling grabbed a revolver out of an icebox where the butter was kept and fired at the attackers, Merlin later testified. One of the gunmen shot Arling three times and he fell dead.

The attackers fled, ignoring the cash register.

Merlin ran to his father, who had fallen face down.

"He was not dead and he spoke to me," Merlin said in court months later, then stopped, overcome.

"Merlin's voice choked here and he wiped his eyes," a reporter for The Salt Lake Tribune wrote. "He was given time to calm himself before another question was asked. Only the muffled grief of the boy was to be heard in the room for a moment."

John raised up on his elbow and asked where the attackers had gone before lapsing into unconsciousness. Merlin went to Arling, then called police, who arrived to find him sobbing.

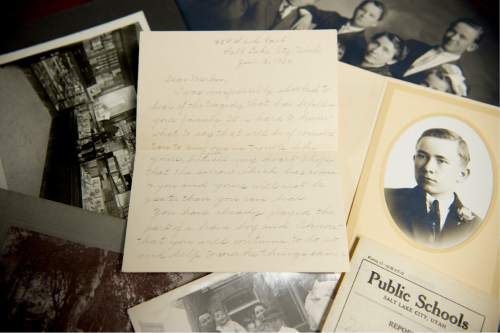

Merlin's teacher, Laura Malin, wrote to him two days later.

"It is hard to know what to say that will be of consolation to any one in trouble like yours," she began. " ... You have already played the part of a brave boy and I know that you will continue to do so and help to make things easier for those you love."

Even decades later, Merlin was haunted by the night.

"As he got older, especially if he was drinking, then he'd really get emotional," said his son Michael H. Morrison, 66, of Taylorsville.

Merlin could not get over the memory of a gun that he said had been within reach as he crouched in the back of the store. He didn't pick it up.

"He froze," said Michael's brother Merlin, named after their father. "That shotgun was the thing that bothered him."

But Merlin, 80, of Mountain View, Calif., and Michael Morrison agree their father would have been killed had he tried to shoot the intruders.

John and Arling were buried four days later, after a funeral attended by hundreds. White sashes draped over Arling's coffin read "Arling Our Hero" in soft purple letters, saluting his courage in firing at the intruders. Police found blood outside the store and concluded that Arling had hit one of the gunmen.

The Morrisons still have the sashes and displayed them at a family gathering early this year.

—

'Brave grocer' • At the time, the motive seemed obvious.

Merlin told The Tribune: "I am sure that the men didn't mean to rob the store, because one of them said as he rushed in: 'We've got you now!' And then he fired. It must have been revenge."

It was the third time John Morrison had been confronted by gunmen, and in between the first two, he had briefly served as a Salt Lake City police officer. Immediately after his murder, police suspected he had been killed by one of the bandits he had thwarted or by a criminal he had arrested.

Born in Missouri, John moved to Salt Lake City around 1890. A circa 1893 family photo shows him at the cigar stand he was running on Main Street. He married Marie, who was born Harriet Maria Nowlin, that year.

Marie's grandfather, a polygamist, had arrived in Utah with Brigham Young in July 1847. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would teach plural marriage until 1890, and Marie's father also was a polygamist.

But her mother, later angered by the practice, left her marriage, the church and eventually the state. Neither Marie nor John was Mormon.

By 1898, John was running his first grocery store, at 470 S. West Temple, where the family also lived.

Returning to the storefront after dinner on Feb. 2, 1903, he was confronted by armed men in masks. Commanded to raise his hands, he instead dropped behind the counter, raced back to the family's rooms and grabbed a shotgun, according to newspaper accounts.

The gun wouldn't fire. He called to Marie to bring him a pistol, then opened up on the robbers.

He was slightly wounded and he wounded one of the men. Later that night, a policeman encountered three suspects and killed one of them in a shootout.

"BRAVE GROCER PUT THREE BOLD ROBBERS TO FLIGHT," proclaimed a front-page headline in The Tribune.

Morrison was soon recruited by Salt Lake City police. But he didn't join the department until January 1906, when the American Party he had joined took control of city government. Founded by Sen. Thomas Kearns, owner of The Tribune, the party aimed to counter the political power of the LDS Church.

According to the Morrison family, he soon developed evidence that an illegal gambling ring was fleecing customers but left the force when no one would listen. John quit on April 1, 1907, just as the department was descending into scandal: Chief George Sheets was charged with using his position to enrich himself.

—

A robbery averted, then murder • The Morrisons opened a new store at 778 S. West Temple, where Mark Miller Toyota now stands. The family lived in a house about two blocks away, at 877 S. 100 West (now 200 West), today the site of a community garden.

John Morrison had acquired other properties and had begun using his Model T pickup truck to make deliveries, said grandson John Arling Morrison. "He was well on his way to making a lot of money in the grocery business."

On a Saturday night in September 1913, John was walking home with the day's receipts when two "highwaymen" confronted him, according to an account in The Tribune. The men fired at John, who was carrying a gun and fired back, and they fled.

John told a reporter for The Evening Telegram that the attackers wanted to kill him, not rob him. He suspected someone in the neighborhood and shared similar fears with friends.

Four months after the attack, John and Arling Morrison were killed.

That same night, Joe Hill showed up at a doctor's home office in Murray with a bullet wound in his chest.

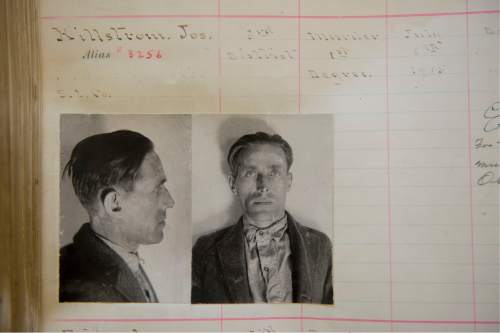

Hill, also known as Joseph Hillstrom, was a Swedish immigrant and itinerant laborer who had arrived in Utah about five months earlier. His biting songs attacked injustice and recruited new members to the IWW, a radical union that aspired to eradicate capitalism and put workers in charge of industrial production.

Hill told physician Frank M. McHugh, a prominent Socialist, that he had been shot in a dispute over a woman. Hill was arrested when McHugh or another doctor tipped off police, but he steadfastly refused to name the woman, the person who shot him or the location of the fight, even when it appeared that information might spare his life.

He was found guilty by a jury and, after an unsuccessful appeal to the Utah Supreme Court, was executed Nov. 19, 1915, becoming an instant martyr for the IWW and the labor movement.

In the century since, historians, writers, legal experts, labor-rights advocates and others have dissected every detail of the evidence against Hill, nearly all questioning the conviction.

John's police career, his gun battles, Merlin's statements that Hill was of the same build, size and height as the masked intruder, and whether Arling actually fired his gun have all come under scrutiny.

—

The next generation • After the murders, Marie took over the grocery store, regularly visiting John's and Arling's graves after work. While John left a significant estate of $18,000, probate court tied up and drained away his assets, his grandchildren said, and the family struggled financially.

The impact of the murders on the five surviving children of the next generation was clear, said Morrison-Ryan. "They were all angry."

Perry, Merlin (known by the family as Mose) and their sister, Blanche, struggled with alcoholism, the Morrison grandchildren said. Perry and Blanche were both in multiple car accidents, including one together that left Blanche in a coma for weeks.

Perry, then 18, had been at his job with the Southern Pacific Railroad the night Merlin witnessed the murders at 13. Blanche was 6.

The brothers had multiple marriages and divorces; Blanche was married once, but according to a family story, her husband left her abruptly as they departed Salt Lake City in a car loaded with wedding gifts.

"They pulled into the gas station. … He left while she was in the restroom," Morrison-Ryan said. "She was already an alcoholic by then and he just didn't want to deal with her."

Robert Morrison, who was 9 years old when he lost his father and Arling, felt a sense of loss and a bitterness that affected him throughout his life. He had "worshipped" Arling, said Morrison-Ryan, Robert's daughter.

The youngest child, James, known as Buck, is remembered as devoted to and sheltered by his mother. He didn't marry his girlfriend of 40 years until he began experiencing symptoms of Alzheimer's disease, not long before he died.

Their anger fueled their politics. Merlin detested unions. Robert opposed socialists and complained with fervor about taxes. He became friends with Reed Benson, who was at one time a staffer of the far-right John Birch Society in Utah, and the son of Mormon apostle and later LDS Church President Ezra Taft Benson.

"They were both big in trying to get people to pay attention to, listening to the right side of the coin," Morrison-Ryan said. "And that was his life. I think he burned himself out on that."

But Merlin, Robert and James were also savvy businessmen. Merlin owned Capital Billiards Bar and Cafe and later bought Midwest Distributing, which distributed Schlitz beer, and other property. He oversaw the building of the warehouse near 300 West and 1300 South, which now houses Granato's, Michael Morrison said.

Robert and James ran the family store for years and started other businesses together. In 1950, a newly built store called Morrison Bros., designed by Robert and still standing at 905 S. State St., was touted as "the most beautiful home and auto supply store in the West."

The surviving Morrison children shared an unshakable belief that Hill murdered John and Arling. "There was no forgiveness for Joe Hill whatsoever," Merlin Morrison said of his father, Merlin.

—

'He's a murderer' • The Morrison grandchildren have individual stories about when they first heard of the murders, but Morrison-Ryan said the family was awash in it.

"I was inundated with it from the time I can remember because they talked about it," she said.

Her brother said he heard details of the murders when he was 15, in the 1940s. A man approached his father, Robert, at the family gas station where John Arling Morrison was working as a teenager. The man claimed to have information about a friend of Hill's named Otto Appelquist.

Police suspected Appelquist was the second attacker at the Morrison store, but he left the night of the murders and never was found.

"This guy said, 'Bob, we know where Appelquist is and we can bring him back to Utah, but it will cost about $20,000,' " John Arling Morrison said. "And he said, 'We can't afford that. We'll have to have the man upstairs take care of it.' "

After that conversation, his father told him about the murders.

Some stories handed down in the family are difficult to verify.

Michael Morrison said his mother told him that Appelquist was once arrested in Texas, and although Robert and James wanted to reopen the case, Marie said no.

Merlin Morrison, the son of Merlin, said his father didn't "believe" Hill was guilty, he "knew" — "because he had seen Joe Hill before when they came into the store and demanded that two men be hired that were union. And in the conversation they told John G., 'If you don't, you'll be sorry.' "

The young Merlin never told that story to police or in court, according to newspaper accounts, and it appears to be an encounter he began describing later in life. The Morrisons' small, family-owned store would not have been a typical target for the IWW, which aimed its organizing efforts at larger industries.

Utah historian John Sillito said he interviewed the older Merlin Morrison in the 1980s. His stories are part of "a solid family lore that isn't written down but is a kind of oral tradition," Sillito said.

Some stories illustrate the strength of the Morrisons' belief about Hill's guilt and their irritation at his celebrity.

John Arling Morrison says he traveled from his Colorado home to Salt Lake City in 1972 to attend a rally promoting the renaming of Sugar House Park to Joe Hill Park.

The park is the former site of the state prison where Hill was executed.

Folk singer Joan Baez, who had sung about Hill at Woodstock about three years earlier, performed at the rally. Each time she mentioned Hill, John Arling Morrison says today, he called out, "But he's a murderer," until an exasperated Baez said, "What's that got to do with it?"

—

'That changed that family forever' • The Morrisons are apprehensive about the coming 100th anniversary of Hill's death and the events and news coverage that will accompany it.

"We don't want to turn it into another glory day for Joe Hill," said Morrison great-grandson Jay Arling Morrison, son of John Arling Morrison. "We've had enough of that."

Grandson Michael Morrison believes Hill was one of the killers, but acknowledges shortcomings in the state's evidence.

"I realize it was circumstantial evidence and had the trial been held today, he probably wouldn't have been convicted," he said.

Critics of Hill's conviction and execution typically raise these issues: He had no motive, the prosecution was based nearly solely on the fact he was shot that same night, there was no reliable identification of him as one of the killers, and his attorneys were incompetent.

Yet Hill remains an enigma for never disclosing details of his alibi — who shot him and where, and the name of the woman they feuded over — when the information probably would have saved his life.

Jay Arling Morrison, like his aunt Morrison-Ryan, tried to read William M. Adler's "The Man Who Never Died," a 2011 book that fingered another suspect in the Morrison murders. He got so mad, he said, that he had to put it down for a time.

Yet, when he takes himself out of the story and looks at the case objectively, "I can see these other theories. The reality is we don't know [who committed the murders]. That's the honest truth about history. We weren't there. We will never know."

Ryan-Morrison acknowledges the terrible working conditions men like Hill faced in the early 20th century, the exploitation and the poverty. But she believes he was used for propaganda purposes by socialists and unions.

"I don't hate the man," she said. "I just don't like them to eulogize him."

Sillito, the historian, is a member of the committee organizing events to remember Hill. But when teaching classes about the Hill case, he said, he always has a moment of silence for the victims of the crime.

"That changed that family forever," he said. "Whether Joe Hill did it or somebody else did it doesn't matter."

—

Tribune photo director Jeremy Harmon and managing editor Sheila R. McCann contributed to this report. —

A controversial, influential folk figure

The Tribune's new site, "The Legacy of Joe Hill," examines the labor activist and songwriter executed in 1915. View rarely seen documents and photos, watch videos of local musicians performing Hill's songs today, and explore the mystery › joehill.sltrib.com

![Jeremy Harmon | The Salt Lake Tribune

This handwritten description of Joe Hill's execution is part of his prison record at the Utah State Prison. (The first names of John and Arling Morrison are incorrect.) It says:

Executed Nov 19th 1915 at 7:22 am - Shot

for the murder of Jack [sic] Morrison store keeper

murder in connection with hold up.

Orlin [sic] Morrison was killed by gun shot

Photo courtesy Utah State Prison](https://archive.sltrib.com/images/2015/0831/hill_Morrisons_083015~8.jpg)