This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The Road Home is a growing public concern because of the visible crime surrounding the Salt Lake City shelter and the plight folks see with the homeless population.

The shelter has suffered several hits in the news media lately, due to stabbings and drug overdoses near the facility as well as homeless residents complaining about unsanitary conditions and communicable diseases.

But the question being debated vigorously — and yet unanswered — is what to do about it.

The Road Home's executive director, Matthew Minkevitch, says the best step is to expand its housing program in which families and individuals are transitioned into subsidized low-income apartments, eventually reducing the shelter's population.

He welcomes the Salt Lake City Police Department's crackdown on drug dealers who mingle among the homeless and peddle their wares to drive-by motorists. The city also has budgeted social workers for the area.

"The job-a-day program has been laudable," Minkevitch says, referring to police efforts to hold twice-weekly seminars with the homeless, hooking them up with temporary jobs and directing them to social-service providers.

The undertaking has come at a cost, he says. Crime around the shelter is out of control. Minkevitch expects the city's new anti-crime push to help. Now the cops can be cops.

But Utah House Speaker Greg Hughes says crime around the shelter is so pervasive "I don't think you can arrest your way out of it."

The Draper Republican has taken an interest in the homeless problem in downtown Salt Lake City after he witnessed three felonies within minutes of speaking to the homeless at one of the police seminars.

Hughes believes the state should become a partner with the city and service providers, and step up to the plate financially, although he is unsure the Legislature has political will to do so.

He favors a secure facility requiring some type of identification card to get into the area, separating the homeless from outside criminal sources.

That would cost money.

Minkevitch says the best approach is to help the homeless not be homeless. Get as many of them as possible out of the shelter and into housing where they can be independent. The housing program is having success now, although the growing number of homeless heightens the challenge.

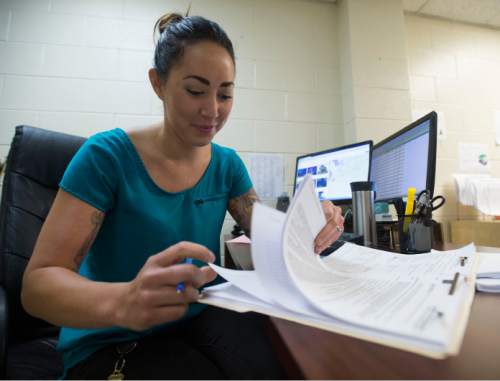

About two-dozen Road Home staffers work to place families and the chronically homeless, especially veterans, into one of the thousand or so apartments the shelter secures through contracts with about 300 landlords in Salt Lake County.

Melanie Zamora, director of housing programs for The Road Home, says the facility spent $3 million in direct rental payments for homeless clients in 2014, almost entirely from federal grants.

But the clients are expected to become more financially independent as they live in the rentals and wean themselves off the subsidies, eventually becoming self-sufficient.

She says 60 percent of those placed in apartments become stabilized after a month. Another 35 percent do so after four months.

Minkevitch says the shelter is pursuing philanthropic funding beyond the federal aid for housing programs and landed some sizable commitments from private donors.

Other issues facing the shelter: the sanitary conditions and danger of contracting diseases there.

My Monday column focused on Kay Adams, a 69-year-old homeless woman at The Road Home who contracted methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a perilous type of staph infection, and eventually had to have part of her colon removed. She now is at the Avalon Valley Rehabilitation Center in South Salt Lake.

While the threat of communicable diseases persists at the shelter because of the large population in such a confined space, staffers do their best to stay on top of it, Minkevitch says. The facility is cleared out at 8 each morning for a thorough cleaning, using hospital-grade cleansers designed to combat MRSA, hepatitis and other communicable diseases.

But just like the crime fighting, it's an uphill battle.