This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Wendover • Ralph Gates was a 20-year-old Army private when he was sent to Los Alamos, N.M., to help Manhattan Project scientists, the brains behind the atomic bomb that — 70 years ago Thursday — fell on Hiroshima.

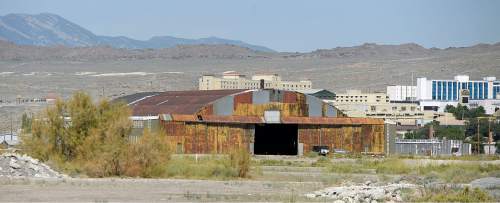

Now 90, he is visiting the former Wendover Army Air Base, which claims a different piece of the history of that top-secret weapon — and the bomb that, three days later, would devastate Nagasaki and lead to Japan's World War II surrender seven decades ago this month.

"I'm impressed," says Gates, who lives in Park City and, for the first time Tuesday, visited the historic airfield on the Bonneville Salt Flats 120 miles west of Salt Lake City.

Gates and several friends saw the pits where bomb prototypes were loaded onto the massive planes, the restored vaults where the then-cutting-edge Norden bombsights were kept under wraps and the B-29 hangar that has come to be called the Enola Gay Hangar.

"It brought back all sorts of memories," Gates says.

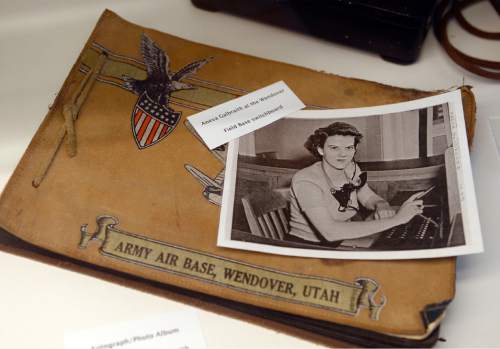

Thousands of airmen learned to fly heavy bombers during World War II at Wendover Army Air Base, which was authorized by a Congress anticipating war and became a sprawling base with 668 buildings after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. Up to 17,000 trained at Wendover at its peak, dwarfing what had been a railroad stop on the edge of Utah's West Desert.

Another 2,500 civilians worked on base.

Fewer than 4,000 airmen were training here, though, by the time the unit that would become Wendover's most famous gathered in spring 1945 — the 509th Composite Group with a super-secret mission.

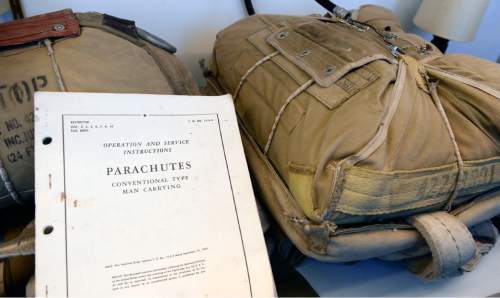

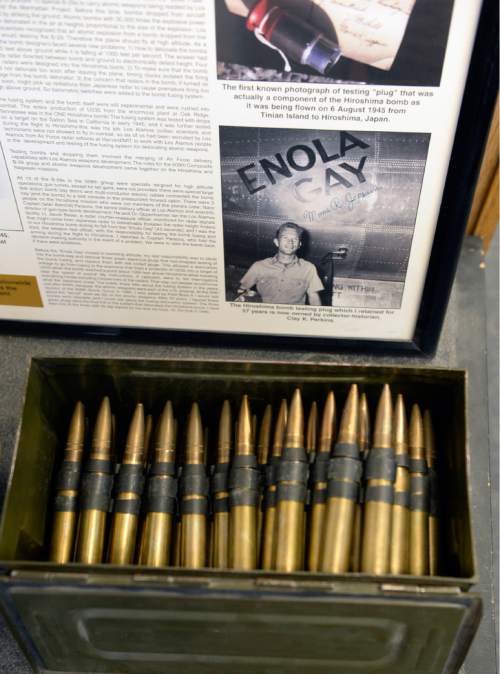

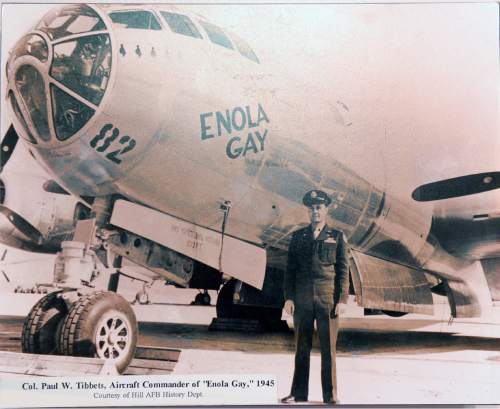

Only one flier — Col. Paul Tibbets, the 509th's commander — knew the truth about that mission in the months the airmen were assembling and testing components, and dropping 150 bomb prototypes over the West Desert and California's Salton Sea.

"The people that were here had no idea what they were working on," says Sandy resident Jim Petersen, president of the Historic Wendover Airfield Foundation and director of aviation for Tooele County and Wendover Airport. (The airport, which gets daily casino-chartered flights and private aircraft, uses the old airfield's runways.)

The 1,700 airmen of the 509th knew only that they were part of some new, highly classified weapons program.

About 400 FBI agents lived on base to keep an eye on them. The airmen's phone calls were monitored, their letters were read, Petersen says. Every week, scientists from the classified Manhattan Project would visit to see the progress in preparations for delivering their bombs to Japan.

Wendover's 103 residents certainly didn't know. Tibbets didn't even tell his crew until the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, when they left the Pacific island of Tinian in the B-29 he had dubbed the Enola Gay (for his mother), bound for Hiroshima.

There, they dropped the world's first atomic bomb, the 9,700-pound Little Boy. Three days later, pilot Maj. Charles Sweeney and the crew aboard Bock's Car dropped an even bigger plutonium bomb, Fat Man, on Nagasaki. More than 80,000 died immediately in Hiroshima, and 40,000 in Nagasaki. Tens of thousands more perished later of radiation exposure.

—

'Hello, Tokyo' • Those working on the Manhattan Project back at Los Alamos, including Gates, had prepared a third bomb and components for several more. But when Japan's emperor announced Aug. 15 that Japan would surrender, those bombs weren't necessary.

Gates remembers "shouts of exhilaration" in Los Alamos when Hiroshima was struck.

"It was nothing but the greatest joy and jubilation," says Gates, who, with others working on the project, had autographed the casing inside Fat Man.

"I remember signing something real crass like, 'Hello, Tokyo!' " recalls Gates, who had a career as a chemical engineer on the East Coast before retiring to Park City in 1990.

"We realized what we were doing had prevented the invasion of Japan," he says. "We knew that hundreds of thousands of people would have died there."

That sentiment, says Robert Voyles, director of the Fort Douglas Military Museum, is common among World War II veterans and those who knew the bombings meant an end to an atrocious conflict.

His own father was a pilot and spent several months as a prisoner of war in Germany.

"You can't find any of those veterans who feel one bit sorry we dropped the bomb," Voyles says. "There aren't any guilt feelings whatsoever."

Voyles himself has mixed feelings and believes the United States and Britain missed earlier opportunities to get Japan to surrender, such as giving the emperor immunity from war crimes.

The Allies' hard-line stance, he says, strengthened Japan's and Germany's resolve.

Yet that's just speculation, he concedes. "In the long run, [the atomic bombs] probably did save millions of lives, including Japanese lives."

The history of the atomic bomb will be one of the topics in a daylong Aug. 15 symposium at the Fort Douglas Museum.

Voyles is also leading a tour group from Fort Douglas to Wendover's airfield the next day.

—

'Trying to forget Wendover' • Wendover's role in World War II often is overlooked, Voyles says, and one reason might be the secrecy that surrounded the Manhattan Project.

Petersen says the records for the 216th Base Unit, which worked on the assembly of the prototype atomic bombs, have disappeared. "We've looked everywhere," he says.

The airmen from the unit were all discharged from their home bases, so there's little record they were in Wendover.

"All those flights [of scientists] from Los Alamos — no record," says Petersen. "It was like [military members] were trying to forget Wendover."

Many Utahns also had forgotten about Wendover's military history by the time it was declared surplus Air Force property in 1976.

The gaming industry on the Nevada side had come to dominate the economies of the twin border towns of Wendover, Utah, and West Wendover, Nev.

But the base, because of the desert climate, still had dozens of buildings intact.

When the Historic Wendover Airfield Foundation took off in 2001, Petersen says, the first move was to put roofs on at-risk buildings.

The airfield is the largest intact Army Air Base left from World War II, with 90 buildings including munitions bunkers. The foundation is raising money to restore more buildings.

The Enola Gay Hangar restoration project was helped by a $500,000 national parks grant but still needs $700,000 to remove asbestos and do other work.

The old officers club is being transformed this summer into a building that will house a new museum (the current museum is in a cramped space). The foundation needs another $100,000 to finish the remodeling.

The Utah National Guard is also restoring a hangar, which, Petersen says, it will use for unmanned aircraft (drone) training.

About a third of the buildings are leased out, including for storage by casinos and others.

"[The base] really is a treasure that needs to be preserved," Petersen says. "This is the one remaining base you can walk through the buildings and see how it was." At present, about 10,000 people a year visit the historic airfield, taking tours and spending time in the museum and gift shop.

Petersen hopes attendance will grow as more buildings are restored and the artifact collection expands. "This really could be the Williamsburg of the Army Air Corps training bases."

Twitter: @KristenMoulton —

70th anniversary of war's end

The Fort Douglas Military Museum plans three events to celebrate V-J Day.

• The premiere screening of the KUED documentary, "Victory," will be Aug. 14 at 6:30 p.m. at the historic Fort Douglas Post Theater, 32 Potter St., University of Utah upper campus.

• A daylong Aug. 15 symposium — "1945: The Year That Changed the World" — starts at 8:30 a.m. at Zions Bank Founders Room, 1 S. Main St., Salt Lake City. Speakers will cover everything from experiences of prisoners of war in Utah to the Japanese internment at Topaz to the atomic bomb. Lawrence Verria, author of "The Kissing Sailor: The Mystery Behind the Photo That Ended World War II," will be a guest speaker.

• On Aug. 16, museum director Robert Voyles will lead a tour to the Historic Wendover Airfield. The bus will leave at 9 a.m., and the $50 cost includes lunch. Reserve a space at the museum website, http://www.fortdouglas.org, by emailing admin@fortdouglas.org or by phoning 801-581-1251. The Historic Wendover Airfield is hosting the 2015 Warbirds & Wheels World War II Commemoration from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Sept. 26. It will be the last reunion for the remaining 509th Composite Group members, who trained at Wendover and dropped the atomic bombs. Brig Gen. Paul Tibbets IV, the grandson of the pilot of the Enola Gay, plans to attend. Information is available at the foundation's website, http://www.wendoverairbase.com.