This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Editor's note: This is one in a series of profiles of members of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah. Find the full story here.

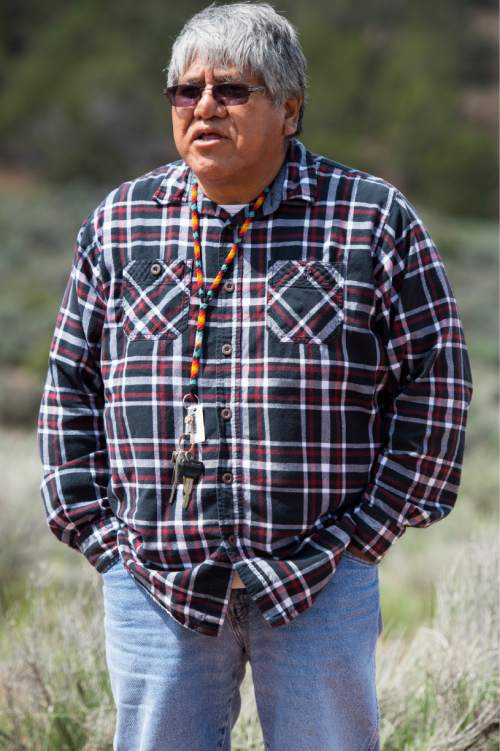

Patrick Charles carries his family pride in memory and story. But the Charles name itself is more like a label, made up for someone else.

His grandfather was named Tu'ab. A federal Indian agent told Tu'ab that wasn't good enough; he needed an English name for a census.

"My grandfather had a white friend named Charles, so he took that name," Charles says. To the federal government, Tu'ab became Foster Charles, father of Kenneth Charles, and grandfather of Patrick Charles — who still considers himself the grandson of Tu'ab.

For a man whose life's work has been, at its heart, about identity, it's ironic (though not unexpected) that Charles' own surname originated as a contrivance to satisfy a white bureaucrat.

Charles, 61, was part of the team of Paiute leaders who in 1980 successfully petitioned Congress to restore federal recognition to the five shattered bands: Kanosh, Koosh arem, Indian Peaks, Cedar and Shivwits. To understand the magnitude of this recovery, it's important to know that the Paiute bands weren't relocated to reservations in one move as white pioneers settled in.

This tiny, geographically fragmented nation has had the rug pulled out from under it again and again, well into the 20th century.

The Paiute bands had held their isolated reservations only for a generation or two when, in the 1950s, federal Indian policy began to take a turn. The new objective was assimilation. Congress and the Bureau of Indian Affairs began exploring which tribes to "terminate," which would remove government protection from the reservations and cancel financial support in order to expedite members' integration into surrounding non-Indian communities.

Although agents reported that the Paiute bands were not ready to support themselves, Utah's Republican Sen. Arthur Watkins, a zealous proponent of termination, pushed them to the top of the list for the experiment. The bands had mixed input, with some opposed and some anxious for the chance to sell reservation lands to alleviate poverty. Congress cut off the bands in 1954.

"I don't think they thought it through," Charles says. "Many didn't know what it meant to be 'terminated.' And taxes were foreign to them."

Many hoped-for land sales ended instead in foreclosures because the bands had no means to pay property taxes. A promised federal payout for 30 million acres that were gobbled up when pioneers settled Utah went unredeemed for nearly two decades, while politicians argued that Indians were too uneducated to make good use of a large cash sum.

The bands were ultimately paid 27 cents per acre.

"That was $7,000 per Indian for all those millions of acres that were taken from them," Charles says.

By that point, $7,000 couldn't fix the damage of termination, much less a century of dwindling resources.

"When termination came, we didn't have anything to look forward to," Charles recalls. "Nobody had jobs. A lot of families didn't stay together. We lost our language. Kids growing up had to struggle with not having a culture. They were no longer Indian, they were just like everybody else. We were trying to be white, when we're not."

As a teenager in the 1960s, Charles had grown angry that, despite the pressure on Indians to "be white," the white community in his childhood town of Richfield seemed none too appreciative of the effort.

"Teenagers would come through the Indian village, throw firecrackers, spin their cars around, torch the outhouse, make fun of the older guys," Charles says. He wanted to quit school but kept his grades up to play football and basketball and eventually attended a semester of college before serving a Mormon mission on Canadian reservations.

Upon his return, Charles could see his tribe was at its breaking point.

"It was the death rate," he says. "We were losing so many. In that little area, all the guys I knew were just passing on. A lot of people passed away because of liver disease. People who didn't die of alcohol died of diabetes. When they're all dying at 30 or 40, you've got to do something to help them. I thought my life expectancy was 50 years old: 'I'll probably die when I'm 50,' I said. Because that was an old man when I was growing up."

Charles had returned to school at the University of Utah in the 1970s when the tribe began to mobilize politically. They needed housing aid, education funds, land, and most of all, health services. Charles joined a delegation in Washington, D.C., to negotiate restoration of the tribe.

They didn't get much of the land they wanted, regaining only a fraction of what was lost during termination. But funds, grant eligibility and, most critically, health support returned. Each band eventually would have a clinic on or near its reservation. Jobs remain a challenge: economic development director Gaylord Robb estimates the unemployment rate for the tribe is at least double the state and national rates. Charles now works as a jobs placement and training specialist for tribal members — a position that didn't exist before 1980.

In three weeks, the tribe's annual powwow will celebrate the 35th anniversary of its restoration.