This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Murray • Debbie Campbell has never had breast cancer, but she has been faithful about getting a mammogram every year since she was 35.

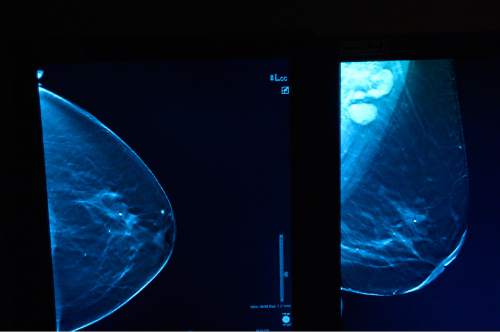

Now 48, Campbell was at Intermountain Medical Center in Murray on Friday for her annual screening.

"It's just common sense," she says.

When her four daughters reach their late 30s, she'll recommend they, too, begin the annual screenings — even if a government task force recommends they wait until age 50.

"People who are in their 40s get breast cancer," says Campbell, who lives in North Salt Lake. "I would definitely start before 50."

Campbell, like a lot of women and, indeed, many doctors, is not putting much stock in guidelines proposed by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

That panel, which doesn't include any breast-cancer experts, last month proposed tweaking mammogram guidelines first issued in 2009. But it did not change the fundamental recommendation that women without a family history of breast cancer begin routine screenings at age 50, and then have them every other year until age 74.

The American Cancer Society and other groups continue to recommend screenings start at age 40.

Not long after that 2009 change, health-conscious women were hit with another change: Pap smears, said the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, should not start until age 21.

Furthermore, women don't need the test for early detection of cervical cancer every year, but every three years until age 30, and then once every five years until age 65 if a Pap smear and HPV test show no sign of problems.

—

Confusion abounds • Brooke Hansen, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the Avenues Women's Center, says she spends a good share of her time with patients going over the recommendations.

"Some people say, 'Thanks for the education, but I'd like a Pap smear every year.' "

The changing recommendations can confuse patients, says Nicole Winkler, a radiologist trained in breast imaging who works at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah.

"It's hard for people in the medical field to figure this out," she says, "let alone the patients."

Doctors generally embrace the 2012 recommendations on Pap smears because they make sense, says Elise Simons, a gynecological oncologist for the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Intermountain Health Care.

Cervical cancer grows slowly, and many abnormalities resolve on their own, particularly in young women with healthy immune systems.

But patients often don't understand the ever-changing recommendations, figuring, " 'I can't make sense of this. I don't know what my risk is. I'm confused,' " Simons says.

The reluctance to test less frequently is natural, she adds.

"It all stems from people wanting to be really vigilant about their care," Simons says, "and we have access to the best screening here in the United States."

But health care costs are high, and over-treatment is a problem.

For instance, young women may be better off forgoing treatment for something that might never become cancer because such care can affect their ability to conceive or carry children.

"Not only is it expensive, but it can be harmful," Simons says. "We're always trying to find the balance."

—

Saving lives • West Valley City resident Susan Bolton is 70 but has no plans to stop having mammograms at age 74. Her internist reminded her it was time for one, and she was at IMC on Friday.

"I'm just going to follow what she tells me to do," Bolton says.

The government task force maintains there's insufficient evidence that mammograms benefit women over 74, but that's based on studies that are decades old, says Brett Parkinson, a radiologist and director of breast imaging at IMC.

As long as older women are healthy and expected to live five to seven years, he says, they should continue to have mammograms.

Parkinson objects to several parts of the government task force's recommendations, the draft of which is open for public comment through May 18 at http://www.screeningforbreastcancer.org.

The American Cancer Society, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Radiology and the Society for Breast Imaging all disagree that women should wait until age 50 before their first mammograms. All suggest annual screening mammograms start at 40.

And there's good reason for that, says Parkinson. "Mammography saves lives."

The task force, he says, is comprised of primary-care physicians, nurses and others from the health care community — but not the radiologists, oncologists or surgeons who deal with breast cancer every day.

"We find it amazing, those of us in the cancer community," Parkinson says, "that the task force would not engage people for whom this is their area of expertise."

Instead, the task force makes what he considers a value judgment about the potential harm versus the risks.

The harm arises if a woman is presumed to have a serious cancer when she has a nonthreatening one, or if she suffers anxiety from false alarms that require more mammograms or biopsies.

Women in their 40s, the proposed recommendations say, should weigh those cons against the prospect that a mammogram might detect cancer.

"I don't want to minimize the anxiety," says Parkinson. But the answer lies in getting a mammogram or needle biopsy results quickly so the woman does not have to worry so long.

Cancers detected in women in their 40s are often the most aggressive, he notes. Moreover, 40 percent of the years of life lost to breast cancer are in women diagnosed while in their 40s.

"And they're telling those women to just make a decision based on a balancing act between harms and risks?"

—

The insurance factor • Breast cancer survivor Sherilyn of Clinton, now 66, says because she had baseline screenings starting in her early 40s, her doctor was suspicious enough of changes in her breast to do a lumpectomy when she was 46. That resulted in a mastectomy and chemotherapy, followed later, when the cancer returned, by radiation.

Sherilyn, who asks that her last name not be used to protect her privacy, says she's a big believer in mammograms. Her daughters now have frequent screenings, and her two sisters were both diagnosed with breast cancer in their 60s and have been treated. Cousins now are more vigilant, as well.

Sherilyn says she had a family history of breast cancer, but didn't know she could inherit the genetic predisposition from her father's family. Two of her aunts died from what started as breast cancer.

The problem with waiting until you're 50, she says, is this: "What if you don't know you have the genes?"

Winkler, at Huntsman, says one of her biggest fears about the task force's recommendations is that insurance plans will stop covering mammograms for women in their 40s without a family history of breast cancer. Screenings can cost hundreds of dollars.

"This may allow insurers to say, 'We don't want to cover mammograms,' " she says. "It doesn't allow women to make the choice themselves."

kmoulton@sltrib.com Twitter: @KristenMoulton