This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The turbines of Utah's oldest coal-fired power plant have stopped spinning.

Rocky Mountain Power took its 60-year-old Carbon Power Plant offline Wednesday, one day before more strict federal mercury-pollution rules went into effect.

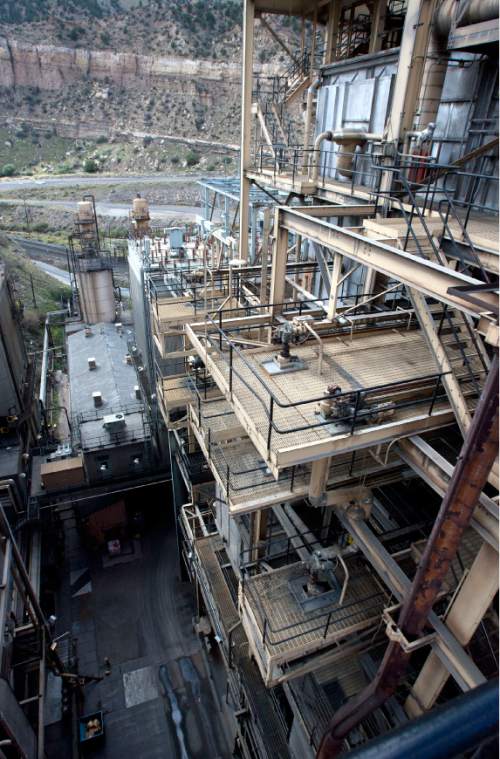

The plant's age and location in a tight canyon a few miles up the Price River from Helper made retrofitting the two-unit, 172-megawatt station a losing proposition, according to company spokesman Dave Eskelsen.

The utility company will spend the next two years dismantling the plant with the help of a contractor.

In the meantime, the plant will maintain a workforce of about 45. The rest of the plant's 74 employees have been shuttled to positions at power plants in nearby Emery County. No plant worker will lose their job.

"Because we had a reasonable notice to prepare for this event, we were able to hold open jobs in other places," Eskelsen said. Nevertheless, "it was a somber day at the plant."

Turning the power off this week was not much different than when the plant was closed for routine maintenance, except that operators had to make sure they were using all the plant's remaining coal.

When Carbon was built in the early 1950s, it represented a shift in American power generation and transmission. Up to that point, Utah's power plants were located near population centers.

Over 60 years, the small plant located in a highly visible spot on U.S. Highway 6 had a reputation as a dependable workhorse in Rocky Mountain Power's fleet.

"It had high reliability — in excess of 90 percent," Eskelsen said. "It had a stellar safety record and routinely went a million man hours without a reportable incident — that's 2½ years."

Carbon was not scheduled to close until 2020.

Now a two-year decommissioning process starts, followed by another two years to reclaim the land.

The gas-fired, 545-megawatt Lake Side Power Station in Vineyard is both replacing Carbon's output and handling growth in demand, Eskelsen said.

Carbon's closure reflects a national trend away from coal, with its hefty carbon footprint, for generating electricity.

Per unit of electricity generated, burning coal emits twice as much carbon dioxide, a chief contributor to global climate change, as natural gas. Coal also emits far more toxic air pollution.

Since 2010, utilities have closed or announced the retirement of 188 coal-fired plants, roughly one-third of the nation's coal-burning fleet, according to Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign.

Those closures prevented 7,800 heart attacks, 82,600 asthma attacks and 5,000 premature deaths, the Sierra Club estimates.

"We know coal is dirty, outdated and increasingly expensive," said Lauren Randall, a Sierra Club spokeswoman.

The announced retirements represent 77,000 megawatts of generating capacity — out of 256,000 megawatts of coal-fired capacity online in the country.

Most of the retired generating capacity will be replaced with cheap and cleaner-burning natural gas and renewable sources, including wind and solar.

As a result, demand for U.S. coal remains flat and is expected to fall if export markets aren't developed.

In central Utah, closing Carbon cuts off a part of the market for Castle Country coal that has supported Emery and Carbon counties for years.

"As we literally make the moves away, there is more space for cleaner energy sources to take hold," said Jeremy Nichols, climate program director for WildEarth Guardians. "It may not be welcomed news in Carbon County, but our energy policy in the U.S. is more than what benefits Carbon County."

For decades, Carbon benefitted the community around it.

Construction of its first unit in 1954 reflected a new ability to generate power a long way from city-dwelling consumers. The plant burned about 650,000 tons of locally mined, sub-bituminous coal a year.

"As transportation costs got more expansive and use of electricity expanded, there were advances made in long-distance transmission technology," Eskelsen said. "It made sense to build large-scale plants near the fuel source."

Accordingly, Rocky Mountain Power developed two major plants in the 1970s at Hunter and Huntington, in the rural heart of Utah's coal country.

Previously, Utah's coal-fired power plants were built in urbanized Salt Lake and Utah counties. The first went up in 1903, near the current site of Salt Lake City's Gadsby gas-fired station on North Temple. Later, the Hale station was built near the mouth of Provo Canyon.

Those plants are long gone, and Rocky Mountain Power has no plans to build new coal plants. Instead, Eskelsen said, the company is looking to natural gas, solar and wind.

The company recently closed its Deer Creek coal mine.

But Rocky Mountain's parent, PacifiCorp, is planning to invest $500 million to upgrade six of its remaining coal-fired plants over the next decade.

Climate activists say that money would be better spent developing cleaner power sources.

A less prominent impact of coal power is ash waste, which activists say can blow around and leach chemicals into groundwater and rivers.

Carbon plant workers deposited its ash in a side canyon about a mile down the Price River, where it will remain permanently.

"It turns to rock," Eskelsen said. "It will remain stable."

This fall, the utility's contractor will demolish the cooling tower and coalyard structures, then turn to the plant's core structures. Two nine-story steel boilers, lined with high-pressure steel tubing, will be dismantled and sold for scrap, along with other large components that cannot be re-used.

By late next year, the plant that for so long powered Utah from its perch in Price Canyon will be gone for good.