This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The University of Utah hopes tiny fish will make big waves at the school's landlocked campus.

Scientists studying cancer have netted a $1.1 million expansion to double the university's supply of zebrafish for a series of studies — research they say could help find new treatments for cancer.

Rodents are still the "mainstay of cancer research," said Rodney Stewart, principal investigator at the Huntsman Cancer Institute Center for Children's Cancer Research. But "if we can do it faster and cheaper with fish, then we'll do it with fish."

School trustees earlier this week signed off on a plan to add more tanks, update equipment and renovate research and office space at the Huntsman Cancer Institute's Zebrafish Core Research Facility.

At the U., a basement aquarium holds 75,000 fish. With the new expansion, the aquarium capacity would grow to 150,000.

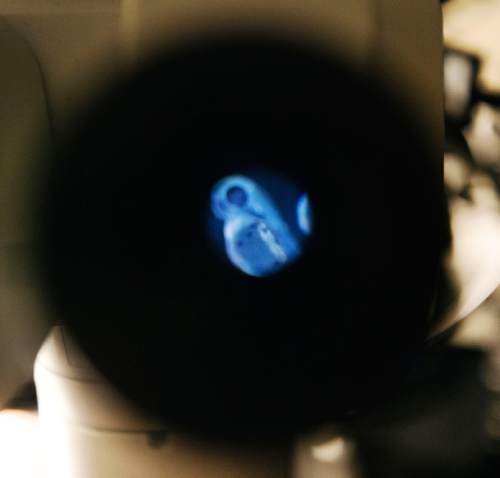

Researchers can trace nearly two dozen different models of cancer through the transparent bodies of the fish, including leukemia, liver and pancreatic cancer, brain tumors and melanoma.

"You can see right through them," Stewart said.

Scientists sometimes inject the fish embryos with cancer cells. In other cases, they observe varieties that are genetically more prone to certain cancers. One such creature circling a tank this week had a bulging eye tumor.

Researchers euthanize sick fish if they swim in spirals or show other signs of pain.

Transparency isn't the only research benefit to zebra fish. Found in most pet stores, they are cheaper than rodents or pricey computer modeling systems, and can be used in larger numbers. The fish allow researchers to test more drugs on a small budget.

"Where you might've had 10 mice, now you can experiment with 10,000 fish," Stewart said, holding a tank of about 20-30 fish.

Low cost is key in studying pediatric cancers which do not attract as much funding because they affect fewer people than other strains.

But there also are drawbacks to using fish. Because they have no mammalian glands, studying breast and prostate cancers is out of the question.

The school of research is relatively new. When Stewart started in 2002, there were only a handful of labs using the tanks. Now, he estimates the number has grown to at least 50.

He came to the U. from Harvard University in 2009 to continue his work, breeding thousands of the silvery creatures native to the Ganges River. Stewart said he can't speak to the specifics of his current research but is planning to release the paper later this year.

The $1,129,000 project still needs final approval from trustees at their meeting later this month.

Twitter: @anniebknox