This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

It can be precarious, Randall Olson learned last year, to yoke university research to a corporation.

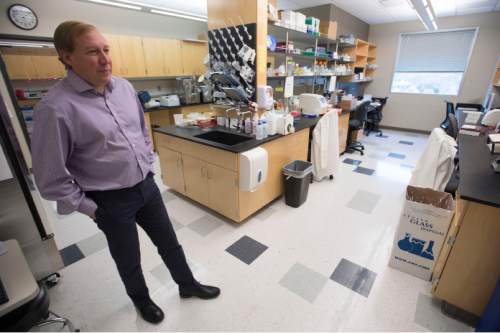

In February, the chief executive of the John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah gushed at a news conference that a new partnership with Allergan Inc. could be a "historic breakthrough" for alliances between academia and industry.

Within two months, the deal looked doomed. Allergan was being targeted for a hostile takeover by a Canadian company intent on gutting its $1 billion-per-year research program.

Corporate machinations threatening a significant research project at the U. is a startling truth of the times.

Research universities like the U. increasingly receive industry funding, particularly in the pharmaceutical sphere because Big Pharma has off-loaded much of its early-stage research to universities and to small biomedical firms.

At the same time, universities are desperate for funds because federal research dollars have been drying up. Utah already gets a higher percentage of its research funding from industry than the typical university, and that proportion is rising.

Allergan, the U.'s celebrated new partner, put up a fight and ultimately was rescued by another giant pharmaceutical company, Ireland-based Actavis, which agreed in November to pay $66 billion for the California-based Allergan.

Actavis says it has no plans to obliterate Allergan's research programs, which should mean the five-year multimillion-dollar partnership with Moran to find treatments for age-related macular degeneration is safe.

Yet Olson remains wary. "Clearly, Wall Street is going to expect to see cost savings," he says.

The uncertainty is vexing, even as Moran researchers in Gregory Hageman's lab and Allergan scientists home in on a treatment that could be in a clinical trial a year from now, a swift, important milestone.

"I've got a lot of white hair on my head from that" takeover drama, says Olson, the U.'s chief of ophthalmology, who last spring was awarded the university's most prestigious honor, the Rosenblatt Prize for Excellence.

—

A push and pull for funding • The new reality is especially stark in medical research. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has lost 25 percent of its funding, adjusted for inflation, since 2003.

And the NIH is by far the biggest single source of funding for research at the U., accounting for nearly a third of all grants.

Health Sciences, which the NIH funds, pulls down most of the U. research money, bringing in nearly two-thirds of the $389 million in universitywide research grants in fiscal 2014.

The realm of Health Sciences includes University Hospital, the medical school, the nursing and pharmacy colleges, Moran and the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Altogether, they get less than 4 percent of their money from state appropriations, tuition and fees. The lion's share of their $2.7 billion budget comes from clinical fees in the hospital, doctor's offices and labs.

Like other leading research institutions, the U. gets an average of 11 or 12 percent of its research budget from companies, compared to about 6 percent at most universities, says Tom Parks, vice president for research.

Data from the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) indicates companies provided nearly 15 percent of the U.'s research budget in 2013, the highest it had been since 1999.

Industry funded even more in Health Sciences — nearly 18 percent of the research budget in fiscal 2013. Among the corporate-sponsored research projects are clinical trials for new medical methods or drugs.

"Corporate America is stepping into the breech," says Jorje Contreras, a new U. law professor who teaches intellectual property and serves on the advisory council for the NIH's National Center for the Advancement of Translational Sciences.

"It's as much pull from the universities as it is a push from the corporations."

—

'Our job is to cure diseases' • So why do universities take corporate money for research and also encourage faculty to commercialize their ideas?

For starters, it's the law, says Parks, a neurobiologist who co-founded NPS Pharmaceuticals, a U. spin-off, in 1986.

The Bayh-Dole Act, passed in 1980, made the intellectual property — inventions, technological advances — developed by faculty doing federallyfunded research the property of universities.

The law was designed to get universities to patent those ideas, to move them from ivory tower to market.

"It's a condition of accepting the federal research money that we will commercialize the findings," says Parks. "Our job is to cure diseases using federal money."

Contreras, the U. law school professor, says before Bayh-Dole, federal agencies had a mishmash of policies, and many ideas were never commercialized because government owned the patents. "It rationalized the system."

But it has had bad consequences as well, says Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, a Washington non-profit.

Universities were traditionally independent sources of knowledge, distinct from and often critical of the corporate sector, he said.

"We've seen that independence very substantially eroded and that critical voice diminished," says Weissman.

Bayh-Dole created internal lobbies for commercialization within universities, and that short-circuited "all kinds of opportunities to think critically about the research enterprise," he says.

For instance, if universities were not thinking so much about making marketable products, there might be as much research into the environmental causes of cancer as into cures, he says.

"The universities start thinking of themselves as market participants and not really as universities," he says.

Moreover, universities have created "patent thickets" so dense that follow-on research is discouraged, he said.

And they aren't thinking about taxpayers when they let drug companies charge exorbitant amounts for drugs developed first on the public dime in academic labs, Weissman says.

"What the universities have done, aided and abetted by others," he said, "is they've created a theory where the only public interest in licensing is getting a product to market."

—

Uncertainty for basic science • Kenneth Kaitin, director of Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development in Boston, says pharmaceutical companies are benefiting from their tighter ties to universities, which allows them to "de-risk" some of their drug development.

They're beginning to bring more new drugs to market and their stock prices are improving.

But more of the risk now rests with universities, as the Moran Center learned in the Allergan hostile takeover drama.

"An entire research program could end in a day," Kaitin notes.

His biggest concern, however, is the lack of funding for basic science, now that NIH and industry focus so intently on translational medicine — getting medical treatments to market.

There can be no translational science without basic research, says Kaitin.

"It's the fuel that makes drug development work. If you don't have the fuel, the whole thing will grind to a halt."

But stripping all risk from the equation would mean no good idea ever gets to the market, Parks says.

"We're always trying to calibrate the risk and the opportunity," he says. "We don't think there is excessive risk in any of the corporate deals we do."

—

From lab bench to business • Allergan is not just funding research — it's also hoping to license the discovery that leads to a marketable cure.

The strategy, called technology transfer, is the other side of the university-industry coin. Companies, sometimes owned by U. researchers, license discoveries made at the university and try to commercialize them.

In 2013, the U. was No. 3 nationally with 23 such businesses launched, according to AUTM. (The university uses a fiscal year, and says it had 17 startups in fiscal 2013).

Many of these U. spinoffs fail early on. That was particularly true in the heady days after the U. hired Brian Cummings to ratchet up tech transfer. Between 2006 and 2011, when Cummings left mid-year, 114 startups were created.

More than half are now "inactive," according to the latest annual report from the Technology & Venture Commercialization (TVC) office, which helps steer faculty ideas into spin-offs or established companies.

Companies appear to be getting a better start under new office leader Bryan Ritchie: Only three of the 45 startups created since the beginning of fiscal 2012 were listed as inactive.

The university didn't always take an ownership interest on every company spun out of the U., but it does now, Ritchie said in an email.

Only a fraction of inventions declared by faculty ever make them or the U. any money. Of the more than 5,500 inventions disclosed over 45 years, only 3.4 percent produced revenue for the U.

Still, a few do hit it big. Three U. spin-offs produced $1 million or more in licensing fees for the U. in 2013, according to the most recent AUTM survey, a total that tied the U. with 10 other schools for 16th in the nation.

TVC takes in about $16 million per year from royalties and licensing fees on patents as well as sales of stock; it spends about $15 million a year, including passing along a share of the income with inventors and their academic departments, Parks says.

More than half of its revenue now is from companies in the biomedical field, such as Myriad Genetics and Biofire Diagnostics, which sells a breadbox-sized diagnostic machine that hospital labs are snapping up fast.

The TVC and University of Utah Research Foundation negotiate how much companies pay the U., and the state's open records law allows companies to demand secrecy for the financial terms. The details of how much Myriad has paid the U. from the sales of its breast cancer genetic tests, which can cost up to $4,000, are unknown.

The U., after a prolonged records fight with The Tribune, provided the Allergan-related contracts, but with all financial details redacted. If the Moran-Allergan alliance results in a cure, the amounts of money Hageman, Moran and U. get will not be made public.

The university says it has checks and balances to manage faculty conflicts of interest and commitment as they run companies. Faculty are given one day per week to devote to outside work, such as consulting or entrepreneurial ventures.

Conflicts are inevitable, says Olson at the Moran Center.

"What they mean is we're trying to do something!" he says. "If we were just about the discovery process and not about the treatment process, then frankly, we're just spinning in academic air."

—

Changing medicine • Dean Li, one of the medical school's star principal investigators, was thinking seriously about conflict of interest in late 2013 when he demanded that a student's parents and wife come talk to him.

Chris Gibson was telling Li he wanted to quit medical school mid-stream and before finishing his doctorate so the two of them could create a start-up drug discovery company, Recursion Pharmaceuticals.

"In what universe does it make sense to drop out and do a business?" Li, vice dean of research for the medical school, recalls thinking as he contemplated what Gibson's parents might say.

Li did not want them or Gibson's wife, Summer Gibson, a neurologist at the U., to think he had twisted Gibson's arm.

"I can't be the Pied Piper. It can't be me convincing him to quit," says Li.

Gibson found Li's demand to meet his parents "embarrassing," but thinks Li wanted to drive home the gravity of leaving school without his medical degree.

Gibson had his entrepreneurial family's support and even enlisted a former undergraduate classmate at Rice University, Blake Borgeson, as a co-founder in Recursion. Borgeson is completing a doctorate in bioinformatics at the University of Texas-Austin.

Recursion is using high-resolution imaging technology and high-level computing to try to match diseases with treatments already tested on humans. The idea is to "repurpose" drugs, many of them sitting in drug-company freezers because they didn't make the cut for the disease they were originally targeted.

Gibson's dissertation for his doctorate is on research he did in Li's lab and published last month in the journal of the American Heart Association, Circulation. Using the same know-how behind Recursion, he found that Vitamin D may be a good treatment for cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM), a rare hereditary disease that can lead to blood vessels hemorrhaging in the brain.

Recursion's goal is to find 100 such "new" drugs in 10 years.

"This is a drug discovery thing, but it's in some sense an IT play," says Li, who spends roughly a fifth of his time on the year-old company — the amount of time allowed all faculty for consulting or other outside pursuits.

To Li, the university can't emphasize innovation — even commercialization — enough, particularly to students who must always look for a better way to do medicine.

"Our job is to do research so that we change medicine," says Li.

Parks says the U. does not deal naively with corporations. "We understand our obligations to protect public funds," he says.

Nonetheless, "We have to have partners in industry to put pills in bottles," he says.

Olson says that in spite of the threats to Allergan last year, the partnership so far is fruitful and he's confident it will produce the world's first good treatments for age-related macular degeneration.

"That would be the single most important thing I could say I did in my life," he says. "That's the hope. That's the dream."

Twitter: @Kristen Moulton